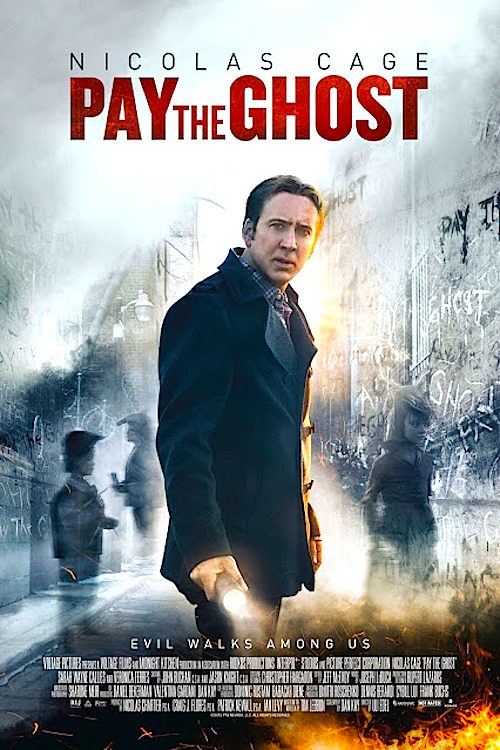

By Joe Bendel. Who would have known a pagan Irish ghost could carry such a grudge? Annie Sawquin was done wrong during the days of Old New York, so her vengeful spirit is not about to let Lower Manhattan off the hook centuries later. Frankly, she has a right to feel put-out. Unfortunately, every year on Halloween, the specter takes out her frustrations on three innocent children. Mike Lawford’s son Charlie was taken last year, but he hasn’t given up hope of finding him. At least as a tenured professor he will have plenty of time to look in Uli Edel’s Pay the Ghost, which opens this Friday.

In his quest for said tenure, Lawford somewhat neglected his wife Kristen and son, so when the good news comes on October 31st, the newly secured faculty member takes Charlie out to celebrate at the annual Halloween carnival. It is rather conveniently located, since like most struggling academics, the Lawfords own a brownstone in Greenwich Village. Unbeknownst to Lawford, Charlie has been acting strange for the last few days, because he has been targeted by uncanny forces.

One minute Charlie is there, the next he’s gone. It is hard to explain that to his wife, who openly blames Lawford for their son’s disappearance. Yet, as they approach the one year anniversary, both parents have strange supernatural experiences that suggest Charlie is reaching out for their help. Soon, she even starts to forgive Lawford, in light of all the macabre bedlam they encounter. Enlisting the help of Hannah, Lawford’s colleague and mentor, they trace back a series of historical and folkloric clues to Sawquin, a Celtic Pagan, who was scapegoated for a plague sweeping through early Colonial New York. Lawford just might be able to rescue his son, but he has a limited window. Once Halloween is over, the die is cast and last year’s victims will be consigned to the other side forever.

One minute Charlie is there, the next he’s gone. It is hard to explain that to his wife, who openly blames Lawford for their son’s disappearance. Yet, as they approach the one year anniversary, both parents have strange supernatural experiences that suggest Charlie is reaching out for their help. Soon, she even starts to forgive Lawford, in light of all the macabre bedlam they encounter. Enlisting the help of Hannah, Lawford’s colleague and mentor, they trace back a series of historical and folkloric clues to Sawquin, a Celtic Pagan, who was scapegoated for a plague sweeping through early Colonial New York. Lawford just might be able to rescue his son, but he has a limited window. Once Halloween is over, the die is cast and last year’s victims will be consigned to the other side forever.

Believe it or not, even though Ghost represents a collaboration between Nic Cage and the director of the infamous Madonna vehicle Body of Evidence, it really isn’t that bad. Apparently, Edel discovered the magic word that convinced Cage to turn down the mania. Maybe it was “IRS.” Regardless, he indulges in minimal nostril-flaring throughout what is arguably his most restrained performance in years.

Sarah Wayne Callies from the Walking Dead is passable enough as Kristin, but it is not what you would call a showcase role for her. As Det. Reynolds, Lyriq Bent does not have much to either, except defend the honor of New York civil servants, but he wears the part well after playing the cop in all those Saw movies. However, Veronica Ferres (known for films like Saviors in the Night and Adam Resurrected, who must have been confused to find herself in an upstart genre movie like this) adds some much appreciated class and seasoning.

Edel maintains an atmosphere of foreboding and nicely capitalizes on the Lower Manhattan-looking locales (courtesy of Toronto). Screenwriter Dan Kay’s adaptation of Tim Lebbon’s novella also accentuates the intriguing backstory and old world details. It all hangs together quite cohesively until quite late in the third act, which is downright impressive by horror movie industry standards. Recommended for horror fans looking for something with a Halloween theme, Pay the Ghost releases on iTunes and opens in select markets this Friday (9/25).

LFM GRADE: B

Posted on September 23rd, 2015 at 11:35pm.