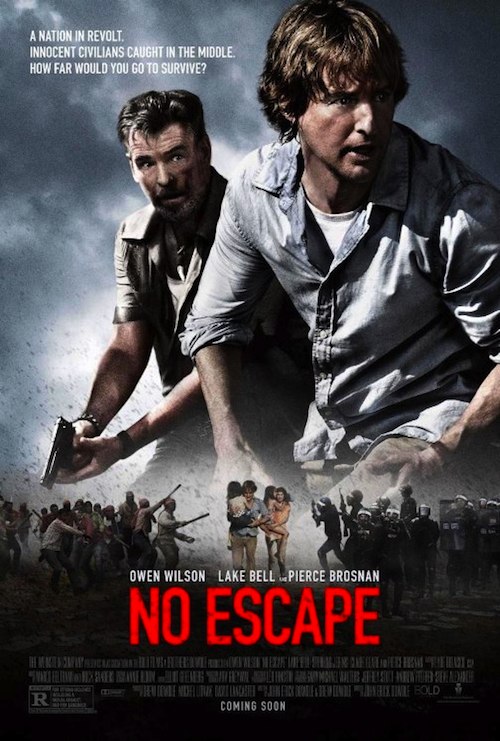

By Joe Bendel. It looks a lot like Thailand, but the use of Khmer lettering somewhat upset Cambodia. The anarchy and mass killings engulfing the fictional Southeast Asian city also rather parallel the brutal fall of Phnom Penh, which could be the real reason for the Cambodian government’s censorship decision. On the other hand, the head of state’s official garb bears a vague resemblance to that of the King of Thailand. Unfortunately, we will not have time to learn if he is also jazz lover and amateur musician, like Bhumibol Adulyadej. The dear leader is about to become the dearly departed, unleashing murderous bedlam in John Erick Dowdle’s No Escape, which opens this week in wide release.

After his tech start-up crashed and burned, Jack Dwyer accepted a middle-manager position with Talbott, an international engineering firm. He is in the process of relocating his family to a country that is one hundred percent not Cambodia but happens to border Vietnam, where he will help construct a water plant. For this he should die, according to the ninety-nine percenters that are about to launch an insurrection. It’s nothing personal, just ideology.

As the terrorists work their way through the Dwyer’s hotel, summarily executing guests room-by-room, Dwyer scrambles with wife Annie and two daughters to safety. He will get some heads-up assistance from Hammond, a suspiciously cool-under-fire Brit. However, things start to get truly desperate when the leftist guerillas call in the helicopter gunships to strafe their presumed safe haven on the roof.

As the terrorists work their way through the Dwyer’s hotel, summarily executing guests room-by-room, Dwyer scrambles with wife Annie and two daughters to safety. He will get some heads-up assistance from Hammond, a suspiciously cool-under-fire Brit. However, things start to get truly desperate when the leftist guerillas call in the helicopter gunships to strafe their presumed safe haven on the roof.

No Escape would be a nifty thriller (sort of like Bayona’s The Impossible, if the tsunami came packing an AK-47), had it not felt compelled to periodically bring the action to a screeching stop in order to blame everything on western imperialism, or is it globalism in this case? In any event, we are responsible, please chastise us. That would be Pierce Brosnan’s job as Hammond, who assures Dwyer the men who just murdered scores of innocent bellhops and office workers are only trying to protect their families, like you Jack. Of course, such moral equivalency is simply farcical.

Believe it or not, Owen Wilson shows some real action cred as the super-motivated everyman. Brosnan also takes visible delight in Hammond’s dissipated tendencies, providing some much needed shtick-free comic relief. Sahajak Boonthanakit also compliments him rather nicely as “Kenny Rogers,” Hammond’s country music loving local crony. However, the film suffers from the lack of a focal villain—a Robespierre to incite the mob.

Despite the shortcomings of the script co-written with his brother Drew, Dowdle certainly has a knack for filming riot scenes. In fact, the first act is quite impressively stage-managed, as we see the Dwyers cut off from contact with the outside world, reacting to dangerously incomplete information. At times, No Escape is a very scary film, but it is frequently undermined by its inclination to lecture. As a result, it falls short of the visceral intensity and unrepentant black humor of the Eli Roth-produced Aftershock. No Escape very nearly could have been great, but instead it is marked by stop-and-start inconsistencies. Still, Brosnan fans will be happy to hear No Escape represents a return to form for the Bond alumnus after a half dozen or so B-level movies, when it opens nationwide this week, including at the Regal Union Square in New York, but not in undemocratic Cambodia.

LFM GRADE: C+

Posted on August 27th, 2015 at 9:15pm.