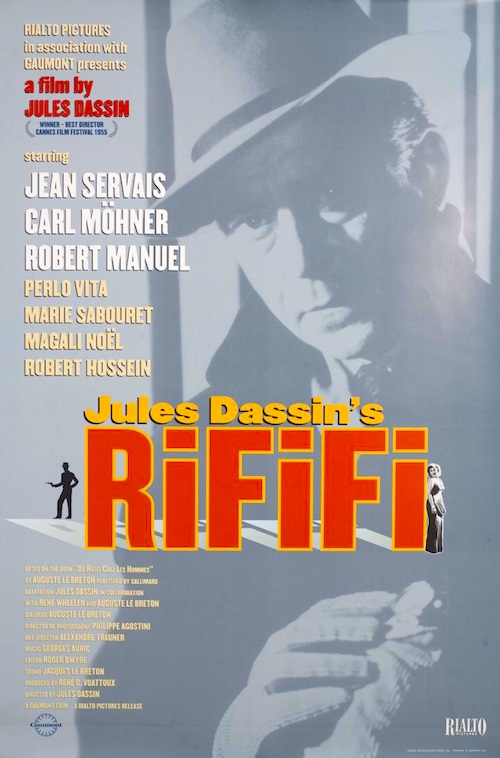

By Joe Bendel. Many think writer Auguste Le Breton joined the French Resistance out of opposition to Vichy’s gambling prohibition. He would survive to become a French Elmore Leonard, known for his gritty action and affinity for slang. As it happened, his source novel was too coarse for genteel American blacklisted director Jules Dassin, who joined the Communist Party in the mid-1930s, right around the time of the Great Purge and the Moscow Show Trials. In order to lose the parts that offended his sensibilities, Dassin expanded the heist scene into half an hour’s worth of wordless action. At one time banned by several countries for its purported criminal instructional value, Dassin’s French noir classic Rififi returns to New York for a special one-week engagement starting this Wednesday at Film Forum.

Tony “le Stéphanois” (from Saint-Étienne) is decidedly the worse for wear after his recent prison stint. He willingly took the rap for Jo “le Suédois (the Swede), whose son Tonio (Tony’s godson and namesake) he dotes on, but his health and finances are in sad shape. To make matters worse, his ex-lover Mado took up with his nemesis, gangster-night club owner Pierre Grutter. After explaining his disappointment to her, Tony will commence planning his next and potentially last big score.

Jo and their mutual crony Mario Ferrati originally conceived of the jewelry store job as a simple smash-and-grab, but Tony wants the prime cuts in the safe. Recruiting Italian safecracker César “le Milanais,” they methodically case the joint and craft their elaborate timetable. The actual half-hour of heist operations is indeed a masterwork of noir filmmaking. However, it somewhat unbalances the film. While there is plenty of good hardboiled stuff in the third act, as the Grutter gang schemes to appropriate the hot ice for themselves, but it necessarily lacks the same hushed intensity of the celebrated centerpiece.

Jo and their mutual crony Mario Ferrati originally conceived of the jewelry store job as a simple smash-and-grab, but Tony wants the prime cuts in the safe. Recruiting Italian safecracker César “le Milanais,” they methodically case the joint and craft their elaborate timetable. The actual half-hour of heist operations is indeed a masterwork of noir filmmaking. However, it somewhat unbalances the film. While there is plenty of good hardboiled stuff in the third act, as the Grutter gang schemes to appropriate the hot ice for themselves, but it necessarily lacks the same hushed intensity of the celebrated centerpiece.

Regardless, Rififi (which very roughly translates as “trouble”) has long been recognized as a noir classic for good reason. Like Le Breton’s books, it has a street smart persona and a street level perspective. It captures the workaday milieu of postwar Paris, especially during the odd hours of the day and night when respectable folks were off the streets. Jean Servais also creates the template for the older, world-weary noir mentor, dealing with the business end of his bad karma. He slow burns like a crock pot with dangerously faulty wiring. Just looking at his lined face makes you want to pop an Advil.

Carl Möhner (probably next most often remembered for She Devils of the SS, which is pretty much what it sounds like), is rather under-heralded for his steady, proletarian work as Jo. However, Dassin himself (billed as Perlo Vita) indulges in a bit of broad ethnic stereotyping, for supposed comic effect, as César.

On heist movie listicals with any sense of history, Rififi inevitably ranks somewhere around number one. It is a film any noir fan has to see to consider themselves literate in the genre. Very highly recommended, Rififi opens this Wednesday (9/2) at Film Forum.

LFM GRADE: A

Posted on August 31st, 2015 at 9:38pm.