[The article below appears in the on-line edition of July’s American Cinematographer magazine.]

By Jason Apuzzo. Over the course of its storied first century, Technicolor came to represent more than a motion-picture technology company. Marked by a vividness of color and an exuberant style, Technicolor became synonymous with an entire era of Hollywood filmmaking, the golden age of studio production from the late 1930s to the early 1950s. This era did not emerge overnight, however, and a new book by James Layton and David Pierce, The Dawn of Technicolor 1915-1935, published by George Eastman House to coincide with Technicolor’s 100th anniversary, documents the company’s earlier, groundbreaking “two-color” era.

It was during this formative period that Technicolor based its technology on the innovative use of red and green filters and dyes — colors chosen to prioritize accurate skin tone and foliage hues. Two-color Technicolor was achieved by way of a beam-splitting prism behind the camera lens that sent light through red and green filters, creating two separate red and green color records on a single strip of black-and-white film. Separate prints of these two color records (with their silver removed) were later cemented together in the final printing process, with red and green dyes then added; this was a complex and error-prone process that later gave way to a two-color “dye-transfer” printing process, in which the color dyes were pressed onto a single piece of film, one color at a time.

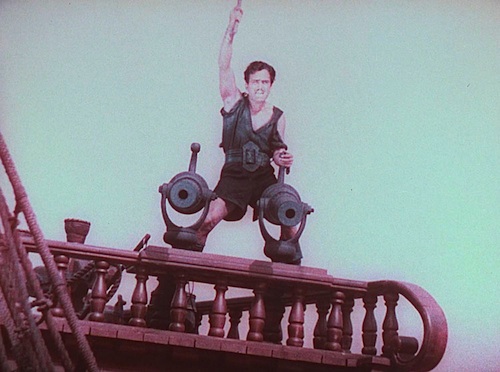

As Layton and Pierce’s book reveals, this early two-color system, which was unable to properly reproduce blues, purples or yellows, was eventually superseded by Technicolor’s more famous, three-color process. Yet surviving motion pictures from Technicolor’s two-color period, such as Douglas Fairbanks’ The Black Pirate (1926) and the color sequences inBen-Hur (1925), reveal a subtlety and understated elegance unique to the technology.

TO READ THE REMAINDER OF THIS ARTICLE, PLEASE VISIT AMERICAN CINEMATOGRAPHER.

Posted on July 10th, 2015 at 5:02pm.