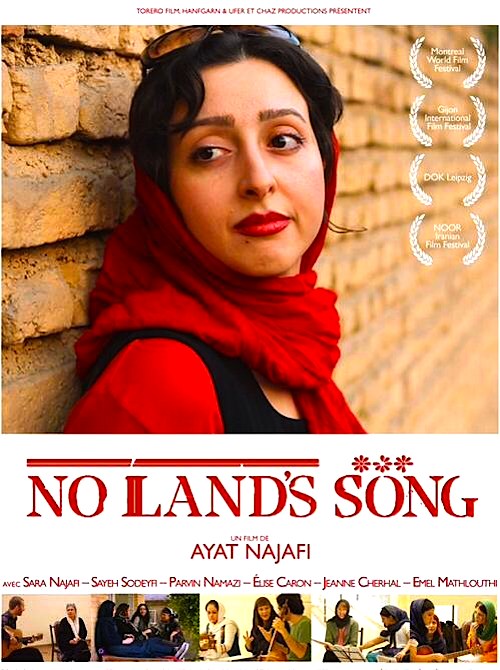

By Joe Bendel. In Iran, the more things change cosmetically, the more they stay the same—or get worse. Since the 1979 revolution, women have been prohibited from publicly performing as vocal soloists. Nevertheless, composer Sara Najafi was determined to stage a concert celebrating women’s voices. Her filmmaker brother Ayat secretly documented the process, capturing her Kafkaesque encounters with the state bureaucracy and religious authorities in No Land’s Song, which screens during the 2015 Human Rights Watch Film Festival in New York.

The prevailing orthodoxy had accepted women as background singers but not soloists for reasons so strained and misogynistic, it is impossible to coherently summarize them. Seriously, it somehow involves Adam’s Rib. This is what Najafi is facing. Her concept for a cross-cultural concert exchange with French musicians is especially unnerving to the apparatchiks with the 2013 election looming. Memories of the Green Movement and the crackdown during the stolen election of 2009 still loomed large. In fact, Najafi conceived the program partly as a tribute to the Green protestors, but she was shrewdly cagey on those details when dealing with the various ministries.

Time and again, we hear bureaucrats dissembling and buck-passing. Clearly, nobody wanted to sign off on Najafi’s program, for fear of reprisals, but they were also reluctant to own up to their decisions. Of course, we can only hear these exchanges, because cameras were strictly prohibited in government offices, but those regime mandated hijabs certainly make it easy to conceal an audio recording device.

Time and again, we hear bureaucrats dissembling and buck-passing. Clearly, nobody wanted to sign off on Najafi’s program, for fear of reprisals, but they were also reluctant to own up to their decisions. Of course, we can only hear these exchanges, because cameras were strictly prohibited in government offices, but those regime mandated hijabs certainly make it easy to conceal an audio recording device.

Essentially, there are two components to NLS, the expose of Iran’s Orwellian ruling apparatus and the musical performances, which eventually do come to fruition, through an improbably fortuitous chain of events. Frankly, they are equally compelling and speak to each other in many ways. Presumably for the sake of their supporters and his sister’s fellow musicians, Najafi is rather circumspect and diplomatic when presenting the backstage events surrounding the concert. Based on his interview with The Guardian, it sounds like it was a much tenser atmosphere than the film suggests.

Regardless, the music was worth the trouble and frustration. Najafi made the most of the opportunity with an awe-inspiringly bold set list. For instance, the lyrics of Emel Mathlouthi’s Tunisian protest song “Kelmti Horra,” performed by the songwriter, do not require listeners to read much into them. The rebellious, free-thinking spirit of Najafi’s program is admirable, but the music is also quite beautiful, often in an almost hypnotic way. Frankly, the short term future of women vocalists in Iran is grimly uncertain. No Land’s Song may not materially advance their cause to any appreciable extent, but Najafi put together a dynamite night of music, which is a worthy accomplishment in itself.

Ayat Najafi’s film is definitely eye-opening stuff. It gives you an immediate sense of what life is like for Iranian musicians, especially women, while also paying tribute to Qamar-ol-Moluk Vaziri, the first Iranian woman to sing in front of mixed audiences with an uncovered head, back in the 1920s. Unfortunately, it does not instill much optimism for the future, but the music is still quite stirring. Highly recommended, No Land’s Song screens this Thursday (6/18) at the IFC Center, as part of this year’s HRWFF in New York.

LFM GRADE: A

Posted on June 15th, 2015 at 10:12pm.