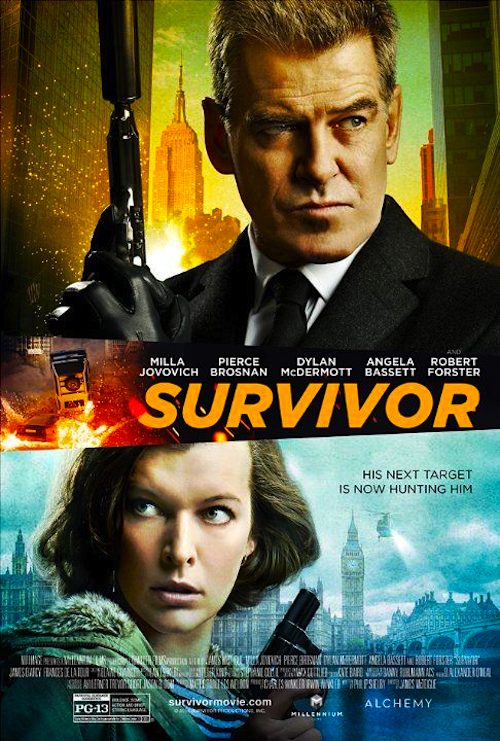

By Joe Bendel. Let’s face it, the terrorists are way more unified than we are. When there is an opportunity to strike a blow against the ever-tolerant West, they will put aside doctrinal differences to make it happen. In contrast, our intelligence and law enforcement agencies are much more concerned about politics, turf management, and general career CYA-ing. At least that is the timely picture that emerges in James McTeigue’s Survivor, which opens today in New York.

Kate Abbott has only been stationed in London for five months or so, but it is clear the Foreign Service security specialist is really good at her job—too good, in fact. When she discovers Bill Talbot, the head of the visa department, has personally intervened to admit several dubious chemical specialists into the country, he quickly arranges to have her killed in a bombing, along with the rest of the visa section. Naturally fate dictates she will be away from the table at the critical moment. That means the assassin, a veteran terrorist known simply as “the Watchmaker” will have to finish her off personally, spy-versus-spy style.

Of course, suspicion immediately falls on Abbott, with the American ambassador and Inspector Paul Anderson, the Scotland Yard point man, being especially obtuse about it all. Only Sam Parker, the senior political officer, believes in her glaringly obvious innocence. Unfortunately, as the Yanks and the Brits chase Abbott, the Watchmaker and his allies have an open field to finish the last stages of their grand WMD conspiracy.

Of course, suspicion immediately falls on Abbott, with the American ambassador and Inspector Paul Anderson, the Scotland Yard point man, being especially obtuse about it all. Only Sam Parker, the senior political officer, believes in her glaringly obvious innocence. Unfortunately, as the Yanks and the Brits chase Abbott, the Watchmaker and his allies have an open field to finish the last stages of their grand WMD conspiracy.

Having helmed the radical favorite V for Vendetta, it is rather odd to see McTeigue associated with a film that considers the mass murder of innocent civilians a bad thing—one to be avoided if at all possible. The credit is probably due to screenwriter Philip Shelby, who co-wrote the second novel in Robert Ludlum’s Covert One series. There are some flashes of inspiration to be found within, particularly with respects to the disturbing but seemingly unrelated prologue, but the film soon settles into a by-the-numbers “Wrong Man” style thriller. It is also disappointing to see Survivor wimping out in terms of the ultimate villains, who are mere schemers hoping to make a fortune selling short.

However, as Abbott, Milla Jovovich is a surprisingly credible presence. After ten or twelve Resident Evil films, we know she has action chops, but she is also convincing playing a smart, reserved character. A Lindsay Lohan or a Megan Fox just couldn’t carry it off. Strangely though, the film does not fully capitalize on her hardnosed potential, forcing her to be a little damsel-in-distress-y at times.

Of course, Pierce Brosnan is no stranger to international intrigue, but he cruises through Survivor on auto-pilot. It is hard to forget how much better he was as a ruthless assassin opposite Michael Caine in The Fourth Protocol. Still, Robert Forster is reliable as ever humanizing the treasonous Talbot (he has his tragic reasons), but James D’Arcy’s unintuitive Inspector seems to be hinting at every repressed, twittish cliché about British public school civil servants.

To its credit, Shelby’s screenplay acknowledges some important realities, such as the events of September 11th, which were Abbott’s motivation for her current line of work. Survivor makes a strong case Jovovich has been grossly underemployed by Hollywood, but as a big picture thriller, it is rather routine. Perhaps worth a look streaming or on cable, Survivor opens today (5/29) in New York, at the AMC Empire.

LFM GRADE: C

Posted on May 29th, 2015 at 9:25pm.