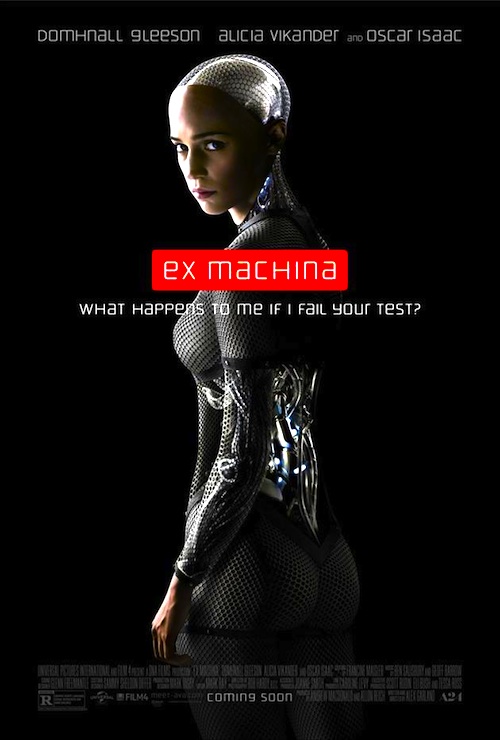

By Joe Bendel. He created a search engine more ubiquitous than Google, but he wants his employees to call him just plain “Nathan.” Of course, he is prickly, condescending, and ethically challenged, but few people have to deal with him, because he is also reclusive. However, Caleb, a bright-eyed coder, has won the opportunity to pal around with his company’s secretive founder in his remote Bond villain villa somewhere in the Alaskan wilderness. It was not a random drawing. “Nathan” has reason to believe Caleb is the right candidate to apply a history-making Turing Test in Alex Garland’s Ex Machina, which opens this Friday in New York.

For Nathan, the challenge of creating an artificial intelligence that can pass the Turing Test is a sufficient reason to create a thinking android like Ava. Any moral reservations are lost on the arrogant and myopic genius. Caleb is a different story, but as soon as he lays eyes on Ava, his enthusiasm increases tremendously.

In seven sessions, Caleb will conduct interviews with Ava to determine if, when, and how her responses deviate from human norms. Granted, it is not a blind Turing Test, but subtleties of meaning that can only be picked up face-to-face are what really interest Nathan and Caleb. Of course, he will be watching through surveillance cameras, except when freak power outages cut the feed (is this Alaska or California?). Ava makes sure that happens regularly during their sessions, so she can warn Caleb not to trust Nathan’s motives or intentions. Thus begins a complicated battle of natural and artificial wits, as she Turing Tests Caleb right back.

Yes, Ex Machina closely follows in the tradition of Bladerunner and Automata, suggesting if the AI apocalypse is coming, humanity probably deserves whatever it gets. Nonetheless, the brainy simplicity of Ava and Caleb’ verbal sparring sessions and the who’s-playing-who drama are intellectually heady and legitimately suspenseful. Despite Ava’s revealing circuitry, it is the notable sort of science fiction film that is far more reliant on ideas than effects.

Yes, Ex Machina closely follows in the tradition of Bladerunner and Automata, suggesting if the AI apocalypse is coming, humanity probably deserves whatever it gets. Nonetheless, the brainy simplicity of Ava and Caleb’ verbal sparring sessions and the who’s-playing-who drama are intellectually heady and legitimately suspenseful. Despite Ava’s revealing circuitry, it is the notable sort of science fiction film that is far more reliant on ideas than effects.

In his directorial debut, Garland (a frequent Danny Boyle collaborator) has an eye for the slightly surreal, but he keeps the sf speculation grounded in the believable and the foreseeable. Strangely though, Nathan’s mysterious Japanese-speaking house servant Kyoko is a more alluring figure than Alicia Viklander’s Ava, but maybe the Swedish thesp is just more compatible with the Nordic severity of the interiors (shot in the high-end Norwegian hipster Juvet Landscape Hotel).

Oscar Isaac channels the dark sides of Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, and John McAfee, delighting in his bouts of manic depressive hedonism and megalomaniacal paranoia. It is a great work of on-screen villainy. In contrast, Domhnall Gleason does his usual sad sack shtick as Caleb, but it suits the film’s needs. Viklander is disconcertingly awkward, like a new born colt of an android, but she and Gleason develop strong chemistry in their interview-and-seduction sequences. Likewise, Sonoya Mizuno’s Kyoko is rather creepy and vulnerable in an enigmatic, wtf kind of way.

Thanks to cinematographer Rob Hardy and production designer Mark Digby, Ex Machina always looks great. Every surface seems to gleam, reflecting the appropriately cool and antiseptic ambiance. It is a smart film that raises a number of issues, deliberately leaving several unresolved. Recommended for fans of intelligent, character (and AI) driven science fiction, Ex Machina opens this Friday (4/10) in New York, at the AMC Loews Lincoln Square and the Regal Union Square.

LFM GRADE: B+

Posted on April 8th, 2015 at 10:13pm.