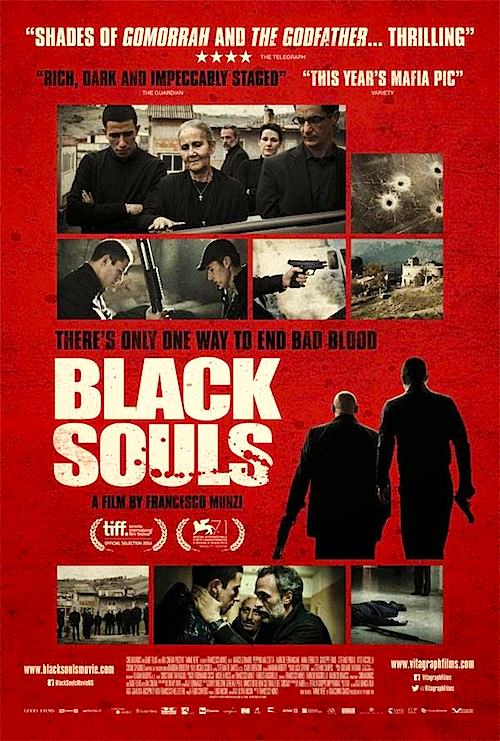

By Joe Bendel. The ‘Ndrangheta is to Calabria what the Camorra is to Naples. Although they are considered more provincial amongst Italian criminal networks, they have an international reach and a presumed alliance with the Sicilian Mafia. Nonetheless, there are still organized along familial lines. Consequently, past grievances often lead to violence and normal family dysfunction can cause long term destabilization in Francesco Munzi’s decidedly un-romanticized Black Souls, which opens this Friday in New York.

Luciano is the oldest of the Carbone brothers, but he largely rejected the family business, preferring to keep a herd of goats and a modest farm in remote Africo, the ancient seat of the ‘Ndrangheta syndicate. His younger brother Luigi is the swaggering public face of the Carbones, while the youngest brother Rocco handles all the dodgy accounting. Luciano’s rebellious son Leo looks up to his uncles, particularly Luigi, the charismatic tough guy.

Impulsively, Leo shoots up a bar aligned with the Carbones’ long-standing rivals, the Barracas, who were responsible for the murder of the brothers’ father. Luigi knows this for a fact, because he was there when it happened. Naturally, Leo’s hasty actions will have serious implications. While Luciano and Rocco are inclined to keep a lid on things, Luigi is sympathetic to Luigi’s injured pride. He has also been planning against the Barracas, but unfortunately, they are way ahead of him.

Impulsively, Leo shoots up a bar aligned with the Carbones’ long-standing rivals, the Barracas, who were responsible for the murder of the brothers’ father. Luigi knows this for a fact, because he was there when it happened. Naturally, Leo’s hasty actions will have serious implications. While Luciano and Rocco are inclined to keep a lid on things, Luigi is sympathetic to Luigi’s injured pride. He has also been planning against the Barracas, but unfortunately, they are way ahead of him.

Inspired by real life events described in Gioacchino Criaco’s novel, Black Souls combines the naturalistic ethnographic detail of Gomorrah with the honor-driven tragedy of a Puzo novel. It reminds us both the word and the concept of “vendetta” came from Italy. For Munzi, it is all about the ‘Ndrangheta’s tribalism and the tension between their old world traditionalism and New World commerce. What happens in Africo directly reverberates in Milan. Despite Rocco’s sophistication and Luigi’s indulgent lifestyle, there are never very far removed from Luciano’s goats. In fact, Luigi’s loyal deputy Nicola can butcher purloined livestock with the best of them.

As Luigi, Marco Leonardi struts like he means business, but Peppino Mazzotta is even more compelling as the bean-counting Rocco, suddenly thrust into a family leadership role. Barbora Bobulova is also terrific as his elegant trophy wife forced to confront the old school realities of the Africo clan. However, Giuseppe Fumo’s Leo is just another petulant teen, who seems to exist simply to move the narrative along with each successive poor decision.

Black Souls is not exactly a groundbreaking Italian gangster movie, but it creates its own distinctive identity in the mountains of Calabria. Munzi builds tension in the right moments and gives viewers an intimate peak inside the ‘Ndrangheta world. Recommended for fans of mob movies, Black Souls opens this Friday (4/10) in New York, at the Angelika Film Center.

LFM GRADE: B+

Posted on April 6th, 2015 at 9:22pm.