By Joe Bendel. Look in your pocket and you might find a smart phone made in Taiwan. They were the only one of the four Asian Tiger economies that largely dodged the regional financial crisis of the late 1990s. However, the Republic of China remains very aware of the extreme poverty it rose out of. The memories of its hardscrabble past were even fresher in the early 1980s, when Edward Yang and Hou Hsiao-hsien introduced the world to Taiwanese auteurist cinema. One of those watershed films was an anthology production Hou contributed to. Fittingly, Hou, Zeng Zhuangxiang, and Wan Jen’s The Sandwich Man screens this week as part of the traveling Hou retrospective Also Like Life, now playing in Vancouver.

By Joe Bendel. Look in your pocket and you might find a smart phone made in Taiwan. They were the only one of the four Asian Tiger economies that largely dodged the regional financial crisis of the late 1990s. However, the Republic of China remains very aware of the extreme poverty it rose out of. The memories of its hardscrabble past were even fresher in the early 1980s, when Edward Yang and Hou Hsiao-hsien introduced the world to Taiwanese auteurist cinema. One of those watershed films was an anthology production Hou contributed to. Fittingly, Hou, Zeng Zhuangxiang, and Wan Jen’s The Sandwich Man screens this week as part of the traveling Hou retrospective Also Like Life, now playing in Vancouver.

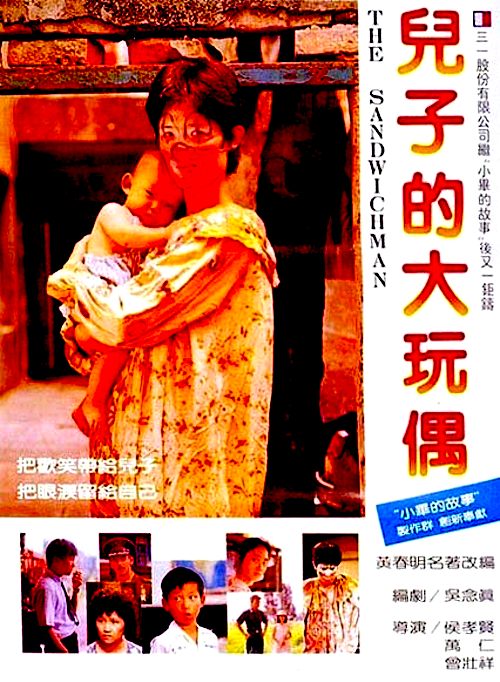

Jin Shu is definitely a crying-on-the-inside kind of clown, but he doesn’t look very cheerful on the outside either. He tramps through his provincial small town wearing his shabby home-made clown costume and sandwich boards advertising the local theater. He has not even been paid yet for his humiliations. This gig was his idea and he is still working on-spec during the trial period. He badly needs work to support his infant son and increasingly impatient wife, but he does not have the right sort of personality for anything involving promotions to the public. Adding further anxiety to his wounded ego, Jin Shu’s little boy no longer recognizes him when he is out of make-up.

In some ways, His Son’s Big Doll (as the story’s title directly translates) also critiqued restrictive Taiwanese laws against contraception that were abolished a few years after the film’s release. It is a relentlessly naturalistic tale about economic desperation, but the surprisingly upbeat conclusion makes it feel like a sort of before-the-fact allegory of Taiwan’s rapid development—just hang on and everything will get better.

Since it is Hou Hisao-hsien and the titular story, The Sandwich Man would seem to be the main event, but the subsequent constituent films are just as good or better. In Zeng’s Vicky’s Hat, two new recruits try to sell Japanese pressure cookers throughout their provincial territory, but they soon start to suspect their product is categorically unsafe. It is a story that has a bit of Glengarry Glen Ross to it, but it is even more concerned with the younger salesman’s halting friendship with Vicky, a mysterious school girl in their neighborhood. There are some fine lines Zeng and his cast must walk—such as establishing his willingness to chastely wait for her to grow old enough for a relationship, but they turn the multiple tragic twists to devastating effect.

Wan’s concluding Taste of Apples is a bit O. Henry-ish—in fact, its irony now seems ironic. A migrant worker is hit by the American military attaché’s car, but this might not be the worst thing that could happen to his struggling family. He will have the best of medical care at the American military hospital, his wife and family will be financially taken care of, and his children will have educational opportunities that never would have otherwise been available to them. Plus, the American Colonel seems genuinely sorry about it all.

Reportedly, the Taiwanese government sought to suppress Sandwich Man because of its portrayal of American government personnel, but considering the anti-American propaganda out there, we should settle for Sandwich Man every chance we get. Sure, we try to fix problems by throwing a bunch of cash around, but that just might work for the family of Apples.

It is also rather fascinating to see how each narrative arc (all adapted from short stories by Huang Chunming, by screenwriter Wu Nien-jen, and shot by cinematographer Chen Kun-hou) speak in dialogue with each other. Those who survived the painful past and make it through the difficult present just might see a better tomorrow, but it will not be easy. A modern classic of Taiwanese cinema, The Sandwich Man could be even more significant when seen in the light of the subsequent thirty-some years of growth and liberalization. Highly recommended, it screens this Thursday (2/26) at The Cinematheque in Vancouver, as part of Also Like Life.

LFM GRADE: A-

Posted on February 25th, 2015 at 9:56pm.