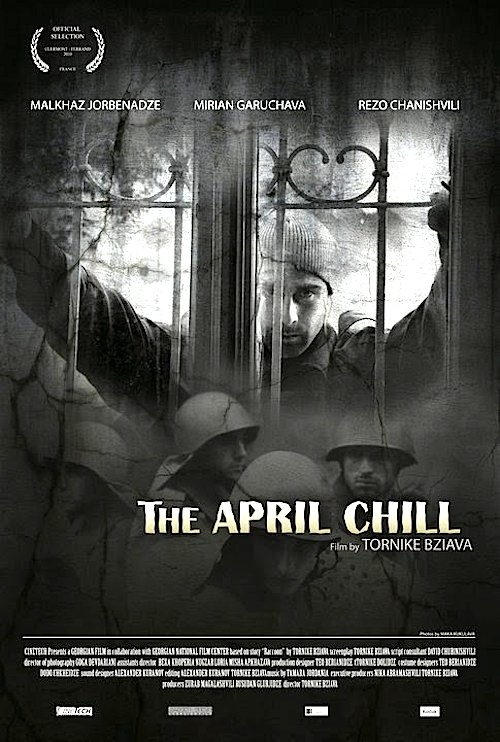

By Joe Bendel. April 9th is now Georgia’s official Day of National Unity. This film shows why. Everybody always assumed good old Gorby would never send in the tanks to crush dissent, but he did in Tbilisi. Hundreds were severely injured and twenty people died that fateful day, seventeen of whom were women. While many were beaten beyond recognition, CN and CS gas inhalation was the primary cause of death. One of the Soviet invaders gets a glimpse of the true warrior’s spirit in Tornike Bziava’s Clermont-Ferrand award winning short film, April Chill, which screens during MoMA’s ongoing Discovering Georgian Cinema series.

By Joe Bendel. April 9th is now Georgia’s official Day of National Unity. This film shows why. Everybody always assumed good old Gorby would never send in the tanks to crush dissent, but he did in Tbilisi. Hundreds were severely injured and twenty people died that fateful day, seventeen of whom were women. While many were beaten beyond recognition, CN and CS gas inhalation was the primary cause of death. One of the Soviet invaders gets a glimpse of the true warrior’s spirit in Tornike Bziava’s Clermont-Ferrand award winning short film, April Chill, which screens during MoMA’s ongoing Discovering Georgian Cinema series.

As several of the Soviet “soldiers” note, it was quite a nice day for their ruthless business. The enlisted men duly follow their orders, chasing democracy demonstrators into barricades, rounding up and beating anyone who looks suspicious. Like good Communists, most of the Soviets seem to enjoy the crackdown, including the focal character. However, the sound of a hand drum and rhythmic counting sparks his curiosity. Within a battle-scarred Soviet Brutalist building, he encounters a young boy learning to perform the traditional military-inspired Georgian Khorumi Dance.

He will learn something about dignity and determination from that boy, but it probably will not be enough to make a difference for his soul or the Georgian people’s immediate well-being. Chill is a brilliantly shot short film that viscerally captures the panic and abject terror caused by the Soviet shock troops. Giorgi Devdariani’s black-and-white cinematography is starkly arresting. He and Bziava frame the action in inventive ways that create jarring perceptual effects. Bziava also uses the imposing Soviet-era architecture to convey a vivid sense of place.

Although Chill is more of a director’s film than an actor’s showcase, there is no denying the fierceness of the young boy. He has the dance chops, too. It only runs for a mere fifteen minutes, but it manages to say quite a bit with great eloquence. Sadly, it is also terribly timely. In 1989, nobody thought Soviet tanks would roll into Georgia, yet they certainly did. Afterward, nobody thought they would ever return, but they already have. Now it’s Ukraine’s turn. April Chill shows viewers just what that entails, in bracingly up-close-and-personal terms. Very highly recommended, April Chill screens with The Other Bank this Wednesday (12/3) and next Wednesday (12/10) as part of MoMA’s continuing survey of Georgian cinema.

LFM GRADE: A

Posted on November 28th, 2014 at 12:57pm.