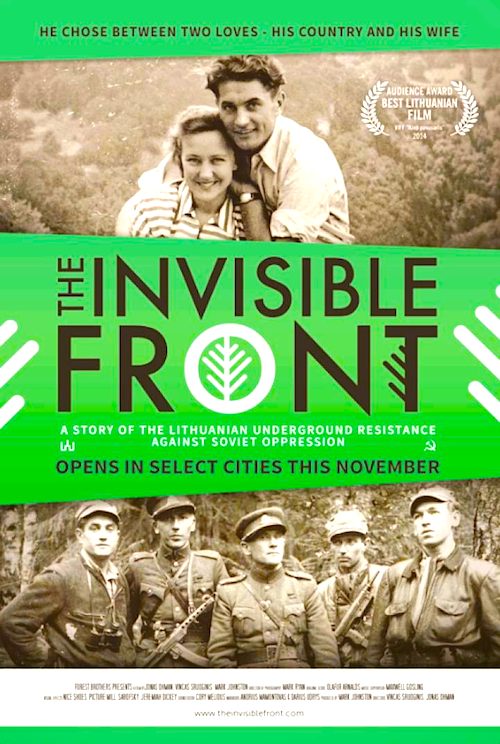

By Joe Bendel. As Putinist forces wage a dirty war against Ukraine, it is hard to avoid the sinking feeling of history repeating itself. However, there is some history he and his separatist lackeys would be advised to remember. The Soviets did their best to banish any mention of the armed resistance to their Baltic occupation from the media and the history books, but the truth will out. The heroic struggles of Lithuania’s partisans are chronicled in Jonas Ohman & Vincas Sruoginis’s The Invisible Front, produced by Mark Johnston, which opens this Friday in New York.

The Baltic Republics were caught in a tight spot during WWII, trapped between two ruthless totalitarian systems. When the Soviets reconquered the Baltics at the end of the war, they commenced a brutal crackdown, hoping to beat the occupied nations into submission. It had the opposite effect.

At its height, one out of every twenty Lithuanians was directly involved with the armed partisan resistance, known as the Forest Brothers—a staggeringly high percentage given the risks. Juozas Lukša emerged from the ranks as the movement’s inspirational leader. He was a warrior when necessary, but first and foremost, he was a journalist documenting Soviet atrocities.

Lukša’s memoir of resistance, The Forest Brothers, provides much of the film’s descriptive commentary, augmented by the testimony of surviving partisan supporters, as well as some of the occupying Soviet oppressors, at least one of whom has since had a change of heart. Unfortunately, America plays the role of the absent cavalry in this story, never interceding on behalf of the Baltics as the Forest Brothers hoped and prayed. It was certainly not for a lack of trying on Lukša’s part.

Several times he clandestinely traveled to the west, hoping to spread awareness of Soviet human rights abuses and thereby spur western action. His efforts were not completely wasted. He met his future wife, Nijolė Bražėnaitė while on assignment in Paris. Needless to say, their romance would be sadly cut short.

Several times he clandestinely traveled to the west, hoping to spread awareness of Soviet human rights abuses and thereby spur western action. His efforts were not completely wasted. He met his future wife, Nijolė Bražėnaitė while on assignment in Paris. Needless to say, their romance would be sadly cut short.

Told through the prism of Lukša’s life, Invisible begins as a war story, evolves into a surprisingly tense tale of espionage, with a heartbreaking romance embedded right in its center. All are stirring stuff, but it is the love story of Lukša and Bražėnaitė that really cries out for a dramatic feature treatment.

Ohman & Sruoginis scored some impressive on-camera interviews, including Bražėnaitė, former Lithuanian President Valdus Adamkus, and at least one former Russian officer who does not realize how ominous it sounds when he explains that they referred to duty in the Baltics as the titular “Invisible Front” because of the complete news blackout throughout the rest of the USSR. (Yet, nobody can say they did not give the other side a chance to speak for themselves). Lithuanian pop vocalist-actor Andrius Mamontovas (excellent in Hong Kong Confidential) adds further domestic star power, sensitively narrating passages from Lukša’s memoir.

Invisible Front is a tightly constructed documentary, arriving at a precarious moment in history, with Putinist Russia is openly aggressing against a free and unified Ukraine. Keenly aware of the film’s timeliness, the production team has started raising funds to supply body armor and medical kits to Ukraine’s volunteer Self-Defense Brigades. It is a worthy cause and a worthy documentary. Ultimately, it is an inspiring film, but it is eerie just how directly it speaks to events unfolding in Ukraine. Highly recommended, particularly for younger viewers who did not live through the Captive Nations era, The Invisible Front opens this Friday (11/7) in New York, at the Cinema Village.

LFM GRADE: A-

Posted on November 4th, 2014 at 8:00pm.