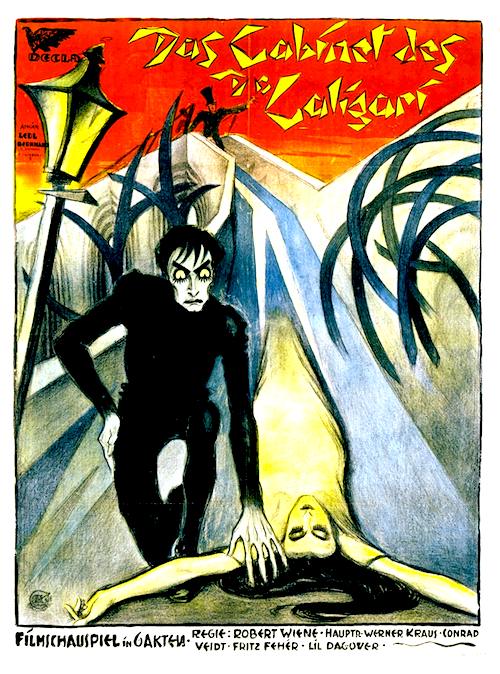

By Joe Bendel. Never ask a sideshow somnambulist when you will die. It is simply too easy for him to make his prophecies come true, especially when he is commanded by a psychotic Svengali with advanced psychiatric training. It is a mistake people still repeat in horror movies. There are a great many such genre motifs that can be traced back to this silent German classic, but the inferiority of public domain prints made it difficult to fully appreciate its feverish vision. Happily, Robert Weine’s ground-breaking The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari has been digitally restored to its original German expressionist glory, or as close to it as humanly possible. After playing to a packed house as part of MoMA’s annual To Save and Project film series, Weine’s restored Caligari opens this Friday at Film Forum.

Like the Ancient Mariner, Francis has a story that will disturb his elderly listener, but it needs to be told. It involves his rather distraught-looking fiancée Jane Olsen, and his best friend Alan. Like the German equivalent of Jules and Jim, both men openly courted Olsen, but resolved to remain friends regardless whom she chooses. Unfortunately, the choice will be made for her when the two friends attend the annual fair.

This year, Dr. Caligari has been granted a permit to exhibit his somnambulist, Cesare, by the soon to be deceased city clerk. According to Caligari, Cesare exists in a state of uncanny slumber, but can be temporarily roused to predict the future. “When will I die,” asks Alan. “At first dawn,” replies the zombie-like Cesare. Late that evening, a hulking figure roughly Cesare’s shape makes the prediction come true. Distraught over the death of his friend, Francis starts pursuing his killer, quickly focusing his suspicions on Caligari and Cesare.

Hans Janowitz & Carl Mayer’s screenplay is considerably more sophisticated than most silent era potboilers, but the ironic framing device was not their idea. In fact, it is largely thought to subvert their ideological intentions. Nevertheless, it is hard to feel comfortable with the authority Caligari represents, despite the eleventh hour twist. Indeed, Cabinet can be seen as an early example of subjective reality achieving equal standing with objective reality.

Regardless, Cabinet is a thoroughly otherworldly environment that only vaguely approximates the forms of our world. Aside from that titular box, you will hardly find any right angles in this town out of time. Instead, everything is made out of jagged lines and slanting diagonals. Janowitz and Mayer’s screenplay was conceived out of aesthetic notions of film as a truly collaborative, inter-disciplinary endeavor, where set designers would be as creatively engaged as actors, writers, and directors. Cabinet might the greatest realization of their egalitarian ideal.

Regardless, Cabinet is a thoroughly otherworldly environment that only vaguely approximates the forms of our world. Aside from that titular box, you will hardly find any right angles in this town out of time. Instead, everything is made out of jagged lines and slanting diagonals. Janowitz and Mayer’s screenplay was conceived out of aesthetic notions of film as a truly collaborative, inter-disciplinary endeavor, where set designers would be as creatively engaged as actors, writers, and directors. Cabinet might the greatest realization of their egalitarian ideal.

Visually, it is an absolute wonder—and a disorienting horror show. The 4K restoration went back to the incomplete camera negative and the best extant prints available, adding footage typically not seen in PD cuts. The original inter-titles have been reinserted and the seemingly abrupt cuts have been augmented with previously missing frames. Gone are the hiss and scratches, replaced by a close approximation of the 1920 color tints and washes. It all looks great on the big screen—and the bigger the better.

Rather inconveniently, it is Werner Krause’s performance as Caligari that holds up best for contemporary viewers. He chews the scenery with villainous relish, shifting gears on a dime when necessary. Despite Cabinet’s lineage, Krause would become an outspoken supporter of the National Socialists and star in Veit Harlan’s notoriously anti-Semitic Jew Süss. On the other hand, Conrad Veidt would play Major Strasser in Casablanca, but he sleepwalks (in a literal sense) through the picture as Cesare. Still, the physicality and theatricality of his work have helped make Cabinet so iconic.

This is a true classic film that has lost none of its power to mesmerize, but the restoration makes it a much smoother and more lucid viewing experience. Almost a century later it remains vastly influential, even though for years it has not been shown in its true glory. Very highly recommended, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari opens Halloween Friday (10/31) in New York at Film Forum.

LFM GRADE: A

Posted on October 28th, 2014 at 5:07pm.