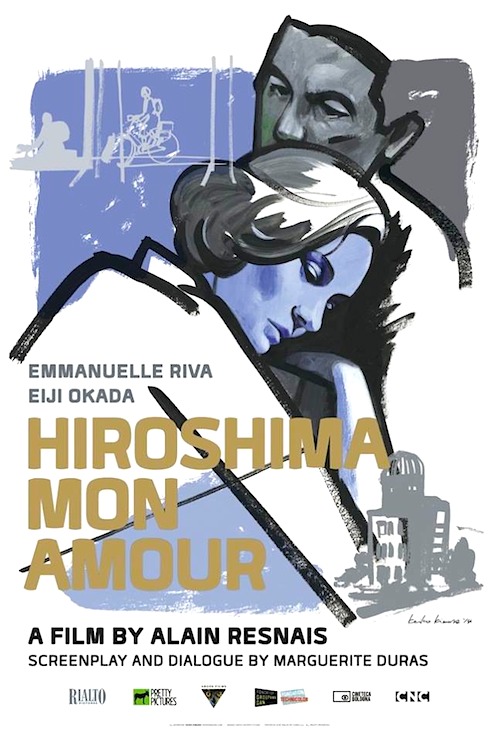

By Joe Bendel. In the late 1950s, Japan was still digging out from the devastation of WWII, while France was struggling with the lingering guilt and shame of the German occupation. A man and a woman representing their respective national psyches will come together in one of the greatest cinematic one night stands to ever carry over into the next morning. “He” and “She” (or rather “Lui” and “Elle”) find brief solace in each other’s arms during Alain Resnais’s Hiroshima Mon Amour, which screened as a revival selection of the 52nd New York Film Festival, in advance of its theatrical re-release next Friday.

She is a French actress who has been shooting a so-called peace film in Hiroshima. He is a Japanese architect, whose wife is usually out of town for extended periods of time. They are both attracted and lonely, on a deeply profound level, so things take their course. However, matters get rather complicated during the afterglow of passion. Despite his apparent contempt for her peacenikery, He has a hard time letting go. She is more inclined to make a clean break, yet she is clearly conflicted. They are both haunted by the past, but her ghosts are especially thorny, rooted in the morally ambiguous era of the National Socialist occupation.

HMA was largely shot in Japan, but it is one of the truly defining films of the French Nouvelle Vague. The long opening sequence plays out like an avant-garde documentary, contrasting newsreel-like images of Hiroshima survivors and the memorial museum with the refrains of an apparent lovers’ quarrel, albeit a rather politicized one: “You saw nothing in Hiroshima, nothing. I saw everything in Hiroshima, everything.”

Eventually, Resnais shows the lovers intertwined, generating eroticism, while also evoking the images and textures of the tragically fused bodies of the Hiroshima atomic blast area or Pompeii. Over fifty years later, HMA is still aesthetically bold, yet somehow Resnais’s radical stylistic shifts are never jarring, rather feeling like they are part of a cohesive whole. It also has a powerful sense of place. By the time it ends, viewers will feel they know Her severely appointed modernist hotel better than their own apartments.

Eventually, Resnais shows the lovers intertwined, generating eroticism, while also evoking the images and textures of the tragically fused bodies of the Hiroshima atomic blast area or Pompeii. Over fifty years later, HMA is still aesthetically bold, yet somehow Resnais’s radical stylistic shifts are never jarring, rather feeling like they are part of a cohesive whole. It also has a powerful sense of place. By the time it ends, viewers will feel they know Her severely appointed modernist hotel better than their own apartments.

As the lovers rouse themselves, HMA almost segues into film noir, following their impossible courtship through a series of late night bars and deserted streets. It all looks eerily beautiful thanks to Michio Takahashi’s arresting black-and-white cinematography. Emmanuelle Riva and Eiji Okada also look like they were chiseled out of Roman statuary marble expressly for this film. They develop some scorching hot chemistry, but also dramatically convey the persistent pain they continue to bear inside. Indeed, HMA is a brutally realistic depiction of the push-me-pull-me dynamic. He and She are trying to use each other to forget, but they perversely spur each other to remember with uncomfortable clarity.

Arguably, you could not make HMA as is, in this day and age. Even though Hiroshima is still acceptable fodder for an anti-nuclear message, the concerted efforts to woo the gatekeepers responsible for Chinese film import quotas would probably demand equal time for Japanese atrocities in Nanjing. Honestly, there are only so many guilt trips one can take in a single film. Fortunately, there are many ways to relate to HMA beyond its anti-nuclear raison d’être. In fact, it is one of the great ships-passing-in-the-night films of all time. Highly recommended for patrons of French and Japanese cinema, the newly restored Hiroshima Mon Amour screened as part of this year’s NYFF, with a proper theatrical release to commence next Friday (10/17) at Film Forum downtown and the Elinor Bunin Monroe Film Center uptown.

LFM GRADE: A

Posted on October 11th, 2014 at 2:45pm.