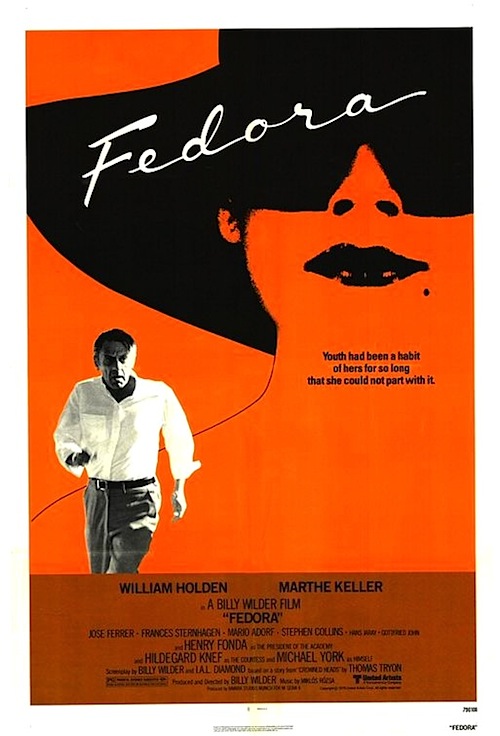

By Joe Bendel. It turns out Norma Desmond was right. By 1978 the pictures had gotten small. One reclusive actress could make them big again, if only she were willing. One scuffling independent producer thinks he has the perfect comeback vehicle for her, but he will have to get past her suspiciously protective entourage in Billy Wilder’s newly restored Fedora, which opens this Friday at Film Forum.

Unlike Desmond, the uni-named Fedora appears truly ageless. Part of the credit must go to Dr. Vando, her personal physician, but he is just as controlling as the rest of her gatekeepers. Fedora is staying at Countess Sobryanski’s villa on the Greek Isle of Corfu, where access is strictly limited. Even though she has rebuffed Hollywood’s overtures for years, Barry “Dutch” Detweiler has come on borrowed money, script-in-hand, hoping to entice her with his modern day remake of Anna Karenina. Since the film starts in medias res at Fedora’s funeral, it is safe to assume the trip will not be a success. In fact, Fedora will dispatch herself in the manner of Tolstoy’s heroine. Of course, there will be a decidedly thorny explanation for her actions.

As we learn in flashbacks, Detweiler has a personal reason to believe Fedora might consider his offer. They once had a fling when she was at the height of her stardom and he was a very junior but very popular production assistant. There will be many more deep dark secrets from the past that Wilder and his celebrated screenwriting partner I.A.L. Diamond clearly enjoyed teasing out.

As a sort of thematic sequel to Sunset Boulevard, starring William Holden as Detweiler, Fedora ought to be beloved or reviled, yet it has been largely overlooked during the succeeding years, instead. Frankly, that is rather baffling, because their dialogue is as snappy as ever and their take on the late 1970s business of moviemaking is drily mordant. There are obvious parallels with Boulevard, but they dress it up with the scandalous trappings of the Harold Robbins novels then in vogue (sex, drug addiction, children secretly born out of wedlock).

As a sort of thematic sequel to Sunset Boulevard, starring William Holden as Detweiler, Fedora ought to be beloved or reviled, yet it has been largely overlooked during the succeeding years, instead. Frankly, that is rather baffling, because their dialogue is as snappy as ever and their take on the late 1970s business of moviemaking is drily mordant. There are obvious parallels with Boulevard, but they dress it up with the scandalous trappings of the Harold Robbins novels then in vogue (sex, drug addiction, children secretly born out of wedlock).

Nevertheless, Wilder was still Wilder, so he could secure some really big stars to appear as themselves. Henry Fonda cranks his likability up to superhuman levels to play himself as the president of the Academy, specially delivering Fedora’s honorary Oscar two years before he was awarded his own. On the flipside, Michael York is quite the good sport appearing as a shallow, clueless Michael York.

Holden proves he can still masterfully handle Wilder’s adult banter, but there is also something poignant about Detweiler’s mounting desperation and nostalgia for the good old days. Even in his final years, he was a true movie star. Marthe Keller is also quite compelling in the title role, which turns out to be quite the complicated part, for reasons that would be spoilery to explain. Likewise, it is great fun to watch José Ferrer’s Vando swill his liquor and chew his scenery.

Sure, Fedora is alternatively lurid and campy—all the best films about Hollywood are, at least to some extent. More importantly, it has the wit and the attitude you would hope for. Not exactly a masterwork and certainly not a masterpiece, Fedora is really just a ripping good exercise in storytelling. Highly recommended for fans of classic movies and the people who made them, Billy Wilder’s Fedora opens this Friday (9/5) at New York’s Film Forum.

Posted on September 2nd, 2014 at 10:55pm.