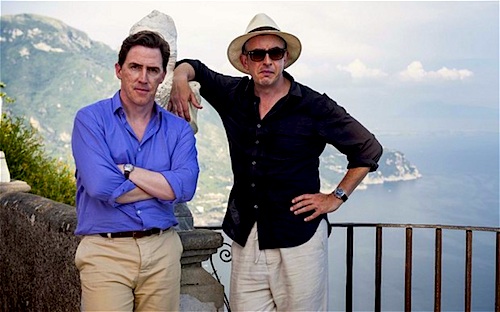

By Joe Bendel. D.H. Lawrence and E.M. Forster found inspiration in Italy. So did Byron and Shelley—a fact Rob Brydon will hardly let Steve Coogan forget. He will quote both poets at length when the celebrity impersonating duo embark on another road-trip in Michael Winterbottom’s The Trip to Italy, which opens this Friday in New York.

Italy might just be the only Winterbottom film that resembles any of his previous work. Clearly sticking with the game plan that proved so winning in The Trip, he turns Coogan and Brydon loose to eat and riff with abandon. Playing somewhat fictionalized and exaggerated versions of themselves (or so we can only hope), the comedians obsess over their careers and complicated personal lives, while touring through Italy for a series of magazine articles.

Just about everyone who saw the original Trip know it as the Michael Caine impression movie (or television show, as it was presented in the UK). There is not the same pitched impersonation battle this time around, but Brydon gives his Al Pacino and Tom Hardy good workouts. Arguably, the Italian Trip is not quite as funny as their tour through the north of England, but the food is considerably more tempting. The second time around will also resonate more with cineastes, who should enjoy their visits to the famous locations seen in John Huston’s Beat the Devil, Jean-Luc Godard’s Contempt, and William Wyler’s Roman Holiday.

Admittedly, both Trips are rather light when it comes to narrative, but it is rather fascinating to watch Coogan and Brydon portray their own somewhat unsympathetic meta-analogs. While Coogan played a rather soulsick Coogan the last go round, he makes a good faith attempt to redeem himself and reconnect with his fictional son in the new outing. In contrast, Brydon goes from being the more likable one to a bit of a cad this time.

If you do not feel like visiting Italy after watching the latest Trip, you were not watching with your eyes open. Winterbottom and cinematographer James Clarke make it look spectacularly beautiful. Brydon and Coogan also land an impressive number of laughs, which Winterbottom wraps up in a surprisingly effective bittersweet bow. Recommended for fans of British comedies and foodie films, The Trip to Italy opens this Friday (8/15) in New York at the IFC Center.

LFM GRADE: B+

Posted on August 13th, 2014 at 10:46am.