By Joe Bendel. Nobody in their right mind would call Mao Inoue homely and the young actress playing her middle school aged self has to be one of the cutest kids ever. Yet, those caught up in the mob mentality will believe anything. Group think in its many guises, including social networking, scandal mongering journalism, and peer pressure, stands thoroughly indicted in Yoshihiro Nakamura’s The Snow White Murder Case, which screens as a co-presentation of the 2014 Japan Cuts and New York Asian Film Festival.

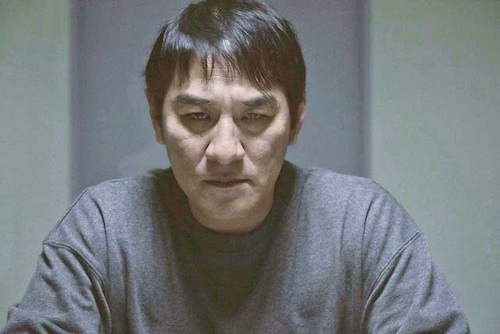

Noriko Miki was Little Ms. Perfect at her cosmetic company (makers of Snow White soap). Outwardly beautiful and gracious, she was actually manipulative and mean. She also happens to be dead, having been found stabbed repeatedly and then burned to beyond recognition. The media will chose to print the legend, led by TV news part-timer Yuji Akahosi, who sees his relationship with one of the murdered woman’s co-workers as his opportunity to hit the big time. During their interview, Risako Kano not so subtly casts suspicions on Miki Shirono, referred to in his reports as “Miss S.”

In subsequent interviews, their fellow co-workers are eager to follow Kano’s lead, especially since Shirono has conveniently disappeared. Slowly, old high school and college friends emerge to defend Shirono. As they tell their stories in flashbacks, viewers see a pattern of bullying develop in her formative years. Yet, Akahosi doubles down on his narrative, egging on the internet’s baying hounds.

Ostensibly a mystery, Snow White is really the sort of film that rips your heart out and stomps on it. All three actresses playing Shirono are just overwhelmingly endearing and vulnerable. Viewers with any sliver of sympathy will be deeply moved by her/their sensitivity and indomitable faith the future will somehow be better.

Snow White was adapted from Kinae Minato’s novel, as was Tetsuya Nakashima’s incendiary Confessions—and it is easy to see a kinship between the two, especially in the way students’ causal cruelty leads to major macro consequences. However, Nakamura’s film does not leave audiences feeling so bereft and numb.

In addition to Inoue and her fellow Sironos, Shihori Kanjiya and her younger alter ego are terrific as Miss S.’s loyal but emotionally stunted childhood friend, Yuko Tanimura. Arguably, Go Ayano is appropriately vacuous and annoying as Akahosi, in a hipster Williamsburg kind of way. Yet, it is TV actress Nanao in her first feature role as Miki, who really gives the film a disconcerting edge.

Considering how intricately plotted Snow White is, the final resolution comes surprisingly quickly and cleanly. Nevertheless, witnessing Shirono’s life is an experience that really gets into your soul. Indeed, its genre trappings are rather deceptive, dressing up an intensely personal drama that steadily expands in scope. Highly recommended, The Snow White Murder Case screens today (7/11) at the Japan Society, as a joint selection of this year’s NYAFF and Japan Cuts: the New York Festival of Contemporary Japanese Film.

LFM GRADE: A-

Posted on July 11th, 2014 at 11:52am.