By Joe Bendel. She drinks Coca-Cola and uses a Statue of Liberty cigarette lighter. Obviously, Boryana’s heart is not in Bulgaria’s glorious effort to build Socialism. It is in Venice. Unfortunately, her unplanned pregnancy will stymie her secret immigration plans. It is one reason why a Cold War rages between mother and daughter in Maya Vitkova’s Viktoria, which screened at the 2014 Sundance Film Festival.

Life in late 1970’s Bulgaria is pretty depressed and dehumanized. Even a trip to the OBGYN is a humiliating experience, conducted in an examination room with windows open for any passerby to observe. Boryana previously used traditional methods to induce miscarriage (a lot of jumping and the like), but to no avail this time.

In addition to putting the nix on Venice, the infant Viktoria perversely becomes a propaganda tool for the state. Not only was she born on Victory Day, she has no navel. Therefore, she is a portent of the new Socialist man of the future. No longer must women take time away from their labor for the sake of childbirth, because babies like Viktoria will surely be incubated outside their mothers.

When it comes to entitled little monsters, none can match a Communist princess. A personal favorite of Bulgarian Party secretary Todor Zhivkov, Viktoria is chauffeured to school each day, where she is given carte blanche to bully her teachers and peers alike. She even has a red phone connection direct to Zhivkov. Then one day in 1989, she becomes an ordinary kid, who nobody likes.

Despite the surreal interludes and mild magical realism, Viktoria conveys a vivid you-are-there sense of life under Communism. There is a ring of truth to it, precisely because of the absurdity. Young Viktoria’s special midriff make-up also looks quite realistic. However, the post-1989 narrative largely loses both its bite and its focus. It seems like it takes Vitkova forty minutes to never really figure out how to end it all. Still, considering the running time is over two and a half hours, there is a good feature’s length of material that works.

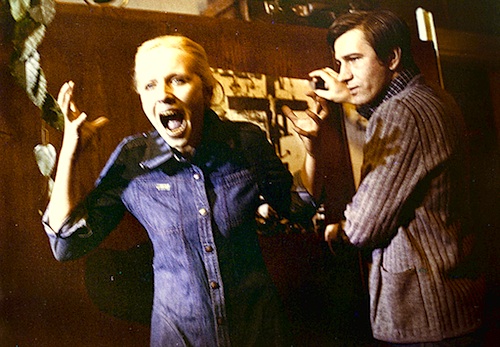

While the third act might have problems, it is hardly the fault of Kalina Vitkova, who is hauntingly expressive as the twentysomething Viktoria. Likewise, her younger sister Daria is a remarkable force as the imperious and then chastened grade school Viktoria. Yet, it is Irmena Chichikova’s Borynana who will really get under viewers’ skin, depicting a persona forced into itself by circumstances and a totalitarian state.

For the most part, the sexually frank Viktoria has the vibe of a more Spartan Unbearable Lightness of Being, with trippy flights of fantasy thrown in to convey the characters inner angst. Highly recommended, it is a challenging film in terms of subject and style, but it is worth grappling with, especially its more consistent initial two hours. The first Bulgarian film selected by the Sundance Film Festival, Viktoria turned out to be a sleeper at Park City, so it is certain to have a long life ahead on the international festival circuit.

LFM GRADE: A-

Posted on February 4th, 2014 at 12:43am.