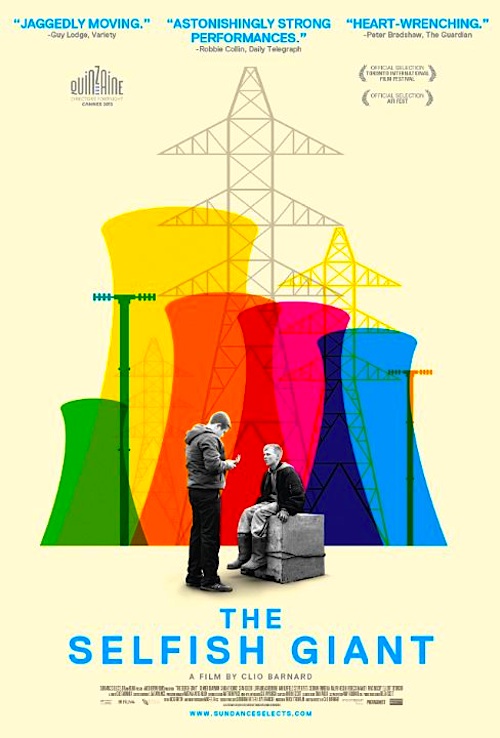

By Joe Bendel. Under the shadow of nuclear containment domes, Arbor Fenton and his mate Swifty collect scrap metal with a horse-drawn cart. It is more or less modern day Yorkshire, but the vibe is often Dickensian. However, it was inspired by Oscar Wilde’s Christian parable. Light years removed from the mythical giant’s garden, Clio Barnard creates her own modern fable in The Selfish Giant, which opens this Friday at the IFC Center.

Forget the “hard kid to love” cliché. The aggressively annoying Fenton is a hard kid not to pummel whenever you see him. It is not entirely his fault. He is the irregularly medicated, hyperactive product of a completely fractured home. Fenton has affection for his mother, but openly defies her parental authority. He is even more contemptuous of his teachers, welcoming his expulsion from school as a personal victory. Fenton has only one friend, the mild mannered Swifty, who was also temporarily dismissed from class due to Fenton’s misadventures.

Forget the “hard kid to love” cliché. The aggressively annoying Fenton is a hard kid not to pummel whenever you see him. It is not entirely his fault. He is the irregularly medicated, hyperactive product of a completely fractured home. Fenton has affection for his mother, but openly defies her parental authority. He is even more contemptuous of his teachers, welcoming his expulsion from school as a personal victory. Fenton has only one friend, the mild mannered Swifty, who was also temporarily dismissed from class due to Fenton’s misadventures.

For Fenton, this is a fine turn of events, allowing them time to collect scrap metal for the dodgy local dealer, Kitten. The grizzled junkman is the sort of authority figure Fenton can finally relate to. However, Kitten has more use for the horse savvy Swifty, whom he recruits to drive his trotter in the local unsanctioned sulkie races. Always unstable, Fenton takes Kitten’s rejection rather badly.

Evidently, Kitten is the giant (after all, he carries an ax during his big entrance), but viewers will be hard pressed to find any other remnants of Wilde lingering in the film. It hardly matters, though. Barnard’s Giant is a grimly naturalistic but deeply humane morality tale. Sort of like Wilde, Barnard ends on a redemptive note, but she really makes viewers work for it.

Eschewing cutesy shenanigans, Giant features two remarkably assured performances from its young principle cast members. It is rather rare to see such a thoroughly unlikable young character on-screen, but Conner Chapman wholeheartedly throws himself into the role of Fenton with a twitchy, petulant tour de force performance. Shaun Thomas nicely counterbalances him as the shy, empathic Swifty.

Barnard masterfully sets the scene and controls the uncompromisingly cheerless vibe, immersing the audience in the profoundly depressed working class estate. Viewers will definitely feel like they are there, sharing their cold, dingy, over-cramped quarters (and doesn’t that sound appealing?). Think of it as apolitical proletarian cinema. Recommended for the work of its young cast and Barnard’s distinctive vision, The Selfish Giant opens this Friday (12/20) in New York at the IFC Center.

LFM GRADE: B

Posted on December 18th, 2013 at 11:40am.