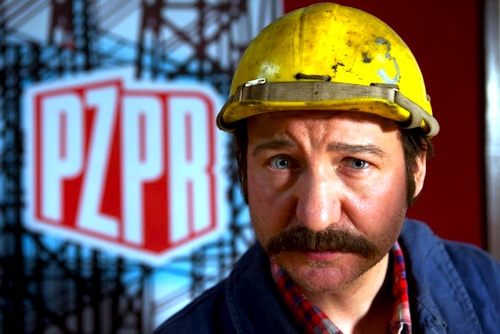

By Joe Bendel. It has been a terrible year for photography. For many, an important form of art and journalism has been debased by the ubiquitous “selfie.” Can a curmudgeonly but self-effacing octogenarian photographer rejuvenate viewer appreciation for the art-form in the age of Kardashian vanity? As a matter of fact, Saul Leiter can when Tomas Leach does his best to profile his somewhat difficult subject throughout the course of In No Great Hurry: 13 Lessons in Life with Saul Leiter, which opens this Friday in New York.

Leiter has been called the “Pioneer of Color Photography,” but he’s not buying it. Frankly, he is rather baffled by Leach’s interest and remains not completely sold on the whole notion of appearing in a documentary. Despite his rather modest appraisal of his career, Leiter is relatively satisfied with the recent publication of his book. Indeed, calling the late, greater-than-he-thought photographer “unsung” might be an exaggeration. After all, at one point in the film Leiter learns he has just been acquired by the Philadelphia Museum of Art (which he thinks is quite nice, but does not exactly have him turning cartwheels). “Undersung” would probably be more accurate.

As skeptical as Leiter is, Leach’s portrait of the artist is surprisingly entertaining, in an appropriately low key manner. Somehow, the audience really gets a taste of Leiter’s personality. We also get a sense of how much history is represented by every pile of slides stacked up in Leiter’s apartment. Frankly, someone could probably make a deeply passionate melodrama about Leiter’s long, complex relationship with model-turned-artist Soames Bantry, but we only get tantalizing hints in INGH. Leiter only offers up tantalizing hints, but piecing together his off-hand reminiscences is part of the film’s charm.

Leach also incorporates many striking photos from Leiter’s oeuvre. Best known for his street level city scenes, often shot through rain streaked store windows, Leiter documented his Lower Eastside neighborhood as it developed over the decades. Although born in Philly, he became a quintessential New York photographer. Although there are several Leiter self portraits in INGH, it is always impossible to make out his reflected features. In many ways, they are the antithesis of “selfies,” but they are perfectly representative of Leiter’s work and personality.

By necessity, INGH is a small, quiet film, because Leiter would put up with just so much. However, Leach’s conclusion still manages to be wonderfully satisfying, yet totally in keeping with his subject’s spirit. For those who love the art form, it comes at an opportune time. Arguably, INGH is the best photography related documentary since (or maybe even better than) How to Make a Book with Steidl, unless you count Bettie Page Reveals All (which is really something completely different). Recommended quit strongly for discerning viewers, In No Great Hurry opens this Friday (1/3) in New York at the Elinor Bunin Munroe Film Center.

LFM GRADE: A-

Posted on December 30th, 2013 at 2:39pm.