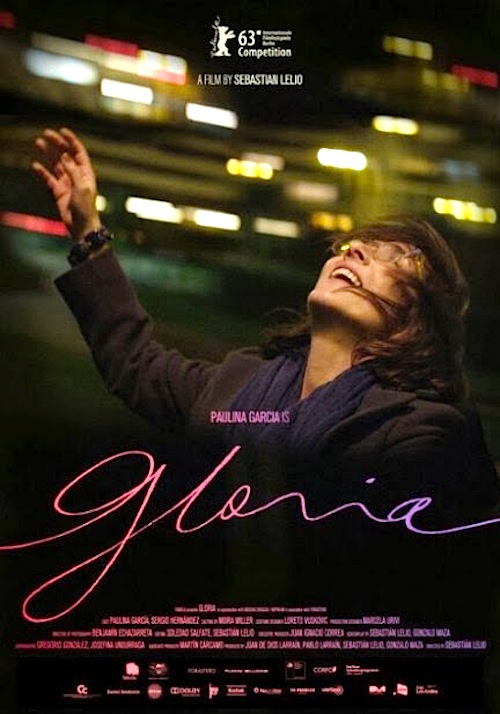

By Joe Bendel. Gloria is a musical name. Hip readers will know Umberto Tozzi was topping the international charts long before his pop song was drastically re-written for Laura Branigan. The bittersweet lyrics of love heard in Tozzi’s original version will nicely suit the protagonist of Chile’s latest foreign language Oscar submission. However, Van Morrison’s “Gloria” never factors into Sebastián Lelio’s Gloria, which screens during the 51st New York Film Festival.

By Joe Bendel. Gloria is a musical name. Hip readers will know Umberto Tozzi was topping the international charts long before his pop song was drastically re-written for Laura Branigan. The bittersweet lyrics of love heard in Tozzi’s original version will nicely suit the protagonist of Chile’s latest foreign language Oscar submission. However, Van Morrison’s “Gloria” never factors into Sebastián Lelio’s Gloria, which screens during the 51st New York Film Festival.

Gloria Cumplido is no stranger to discos. She often haunts them during singles nights. The fifty-eight year-old divorcee always finds a dance partner for the night, but she is looking for something more substantial. She thinks she might have found it in Rodolfo Fernández. They catch each others’ eye across the dance floor and one thing duly leads to another.

Happily, his charm does not evaporate in the morning. In fact, he is rather determined to pursue a relationship with Cumplido, but he has issues. His ex-wife and grown daughters are still unhealthily co-dependent and he continues to enable their behavior. At least, that is the charitable interpretation. Regardless, he gets distinctly flaky at the most inopportune times.

Gloria is small in scope and thin in narrative development, but it has a dynamite lead in Paulina García’s Cumplido. Refreshingly, she is nobody’s victim. She is a woman of a certain age with a reasonable degree of sexual confidence, trying to chart a third act for her life, now that her grown children are preoccupied with their own lives. García brings out her vulnerability, but consistently plays her as smart and resilient, so we never lose patience with decisions.

There are a few laughs here and there (most memorably the odd cat creation story her housekeeper spins out of Noah’s Ark), but Gloria a serious film by-and-large, because it addresses some serious business—love and aging. At times, Lelio is far too enamored with the daily routine of his central character, but he has a keen sense of how to use music. When he finally unleashes Tozzi’s hit tune, it makes the moment. He also shrewdly incorporates a rendition of Jobim’s “Waters of March,” whose lonesome imagery and hopeful spirit nicely reflects her alone-in-a-crowd experiences.

Lelio’s one hundred ten minute running time is far longer than it needs to be. We would most likely get it just as well somewhere closer to ninety. He probably fell in love with his character and lead actress, which is understandable. She carries the film with her boldly revealing performance. Those who have a phobic reaction to unvarnished nudity should be forewarned, but it will strongly resonate with viewers who identify with mature characters and their emotional circumstances. Recommended respectfully (but not wildly enthusiastically) for the target audience, Gloria screens tonight (10/6) at the Walter Reade and tomorrow (10/7) at the Francesca Beale as a main slate selection of this year’s NYFF.

LFM GRADE: B-

Posted on October 7th, 2013 at 12:31pm.