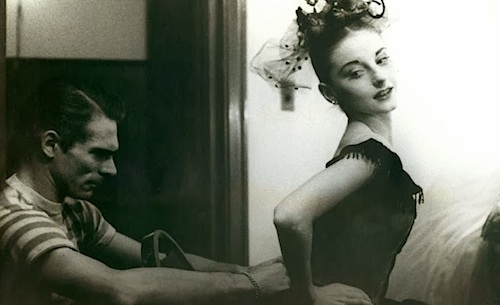

By Joe Bendel. Given his darkly surreal imagery and his penchant for destroying his own work, there is definitely something Kafkaesque about the late Iranian expatriate artist Bahman Mohasses. For years he had removed himself from the world. Yet, he was ready, perhaps even eager to talk when Mitra Farahani tracked him down for her documentary profile, Fifi Howls from Happiness, which screens during the 51st New York Film Festival.

Mohassess is clearly out of step with the current Islamist regime in Iran. It seems his large scale nude statues were not compatible with the post-Revolutionary standards of “decency.” He also happened to be gay, but in a defiantly politically incorrect way (marriage was not exactly a priority for him). However, his first extended period of self-imposed exile began shortly after the Shah’s ascendency.

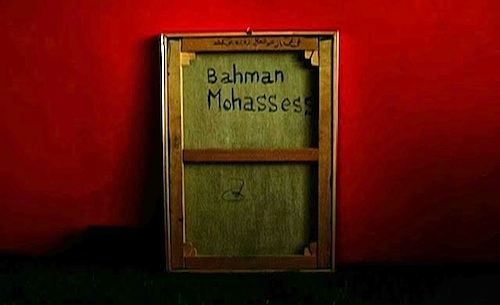

Eventually, Mohassess returned to his homeland, where the Shah’s wife became one of his leading patrons. A far cry from a fundamentalist, Mohassess still gave the Islamic Revolution a fair chance, but eventually tired of the gauche scene. Before he left, Mohassess destroyed a significant portion of his oeuvre, taking only a few pieces with him (most notably including the painting that supplies the title of Farahani’s film).

On one hand, Mohassess’s actions echo the existential self-negation of a Dostoyevsky character, yet at other times one suspects it is all a calculated attempt to create mystique. It almost seems like Mohassess has been waiting for someone like Farahani to take his bait. Regardless, she develops a considerable rapport with the artist, but never sounds nauseatingly fawning.

While not quite deleted from Iranian history books, Mohassess’s place in the nation’s collective consciousness is decidedly ambiguous, which makes Fifi a valuable cinematic record. Clearly, there are still Mohassess collectors, like Rokni and Ramin Haerizadeh, prominent Iranian artist-brothers working in Dubai. Through Farahani, they visit Mohassess to commission what may or may not be his last great artistic statement.

Since Fifi is almost entirely shot in Mohassess’s residential hotel, the film is visually somewhat static. Still, it is fascinating to see the stills of his work, accompanied by his artist commentary, especially considering most of said pieces no longer survive. Farahani cleverly incorporates her subject’s unsolicited directorial advice, ironically following it to the letter. Her extended allusions to Balzac’s The Unknown Masterpiece and Visconti’s The Leopard also add literary flair.

Indeed, Farahani earns great credit for working with and around Fifi’s inherent limitations. Mohassess is a difficult subject, who never sounds like he is really “for” anything or anyone, not even himself. Yet, Farahani does him justice, convincing the audience he is an odd character to visit, but one well worth saving from the memory hole. Recommended for connoisseurs of art documentaries and Mohassess’s work, Fifi Howls from Happiness screens tomorrow (9/28) and Tuesday (10/1) at the Gilman Theater as part of the Motion Portraits section of the 2013 NYFF.

LFM GRADE: B

Posted on September 27th, 2013 at 3:12pm.