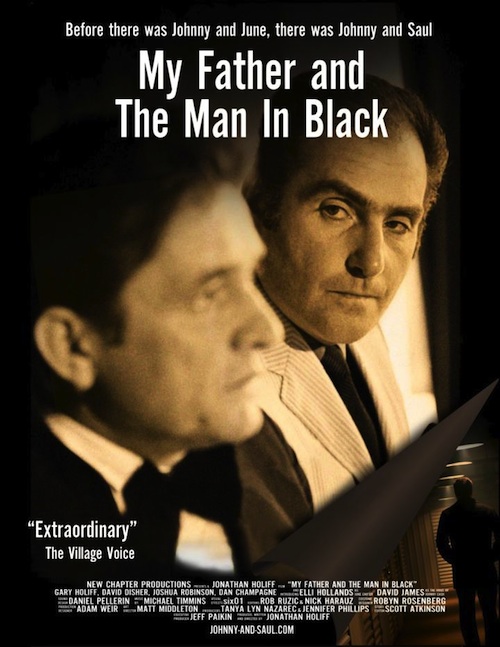

By Joe Bendel. Hallmark ought to start making Manager’s Day cards. The dealings between big name entertainers and their managers are often complex. Saul Holiff was a difficult father, but he managed Johnny Cash’s career with fierce dedication, until the day he tendered his resignation. Discovering his father’s archive, Jonathan Holiff would gain tremendous insight into his father’s relationships with his legendary client as well as himself. Holiff draws upon that trove of primary sources for his documentary, My Father and the Man in Black, which opens this Friday in New York.

As a father, Saul Holiff was often dismissive and demeaning. As a result, his son’s response to his suicide was rather confused. Sometime later, his father’s storage locker came to light. There the younger Holiff would hear his father tell his story, in his own words, left for posterity on his reel-to-reel diary. A born salesman, Saul Holiff fell into promoting concerts in his native Canada. That was how he met the young and relatively unknown Johnny Cash.

Holiff was there, trying his best to cover Cash’s back during the worst of his years of drug-fueled chaos. He was also the one who brought Cash together with June Carter when Holiff recruited a female vocalist for a package tour. However, Cash’s embrace of Evangelical Christianity in the 1970’s clearly chafed Holiff on some level. Still, he did his duty, even appearing as Pontius Pilate in Cash’s Gospel Road, sort of a precursor to Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ. (This could be a moving experience for those who watch it start to finish, but the clips Holiff includes suggest it ought to be playing at midnight screenings for lubricated heathens.)

Holiff was there, trying his best to cover Cash’s back during the worst of his years of drug-fueled chaos. He was also the one who brought Cash together with June Carter when Holiff recruited a female vocalist for a package tour. However, Cash’s embrace of Evangelical Christianity in the 1970’s clearly chafed Holiff on some level. Still, he did his duty, even appearing as Pontius Pilate in Cash’s Gospel Road, sort of a precursor to Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ. (This could be a moving experience for those who watch it start to finish, but the clips Holiff includes suggest it ought to be playing at midnight screenings for lubricated heathens.)

While Holiff the filmmaking son obviously did not set out to burnish Cash’s image, his intimate examination of the Cash-Holiff dynamic might still interest the singer’s fans. To an extent, the doc functions as the revisionist alternative to Walk the Line, but in terms of filmmaking, it is a wildly mixed bag, featuring dubious dramatic re-enactments and far too much of Holiff fils.

Nonetheless, despite the stylistic and editorial missteps, there is an awful lot to engage with throughout My Father. Holiff addresses big picture themes – like paternal legacy, the significance of Judaism for secular Jews such as his father, and the nature of show business – with considerable time and insight.

Eventually, Holiff the filmmaker comes to general terms with Holiff the father. While it is not exactly a rosebud moment, it ends the film in a forgiving spirit. In fact, the film’s messy humanistic vibe is unexpectedly potent. As a film more for documentary watchers than music fans, it might have trouble finding a natural audience, but it has a bit of staying power. Recommended more for those concerned with its issues of family and identity than backstage revelations, My Father and the Man in Black opens this Friday (9/6) in New York at the Quad Cinema.

LFM GRADE: B-

Posted on September 3rd, 2013 at 12:17pm.