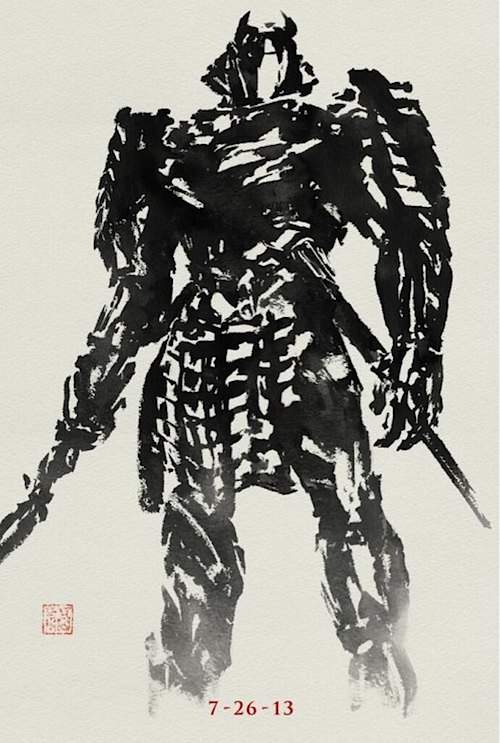

By Joe Bendel. China recently surpassed Japan to become the world’s second largest film market. Yes, China is number two with a bullet, but Japan is hardly chopped liver. As an extra added benefit, studios do not have to debase their product or sell their souls to export films into Japan. Yet they seem to take perverse pleasure in kowtowing to Chinese Communist Party censors. However, the latest Japanese-centric installment of the X-Men franchise surely understood where its international bread would be buttered. Better than initial reviews gave it credit for, James Mangold’s simply titled The Wolverine is worth a look-see in theaters now.

By Joe Bendel. China recently surpassed Japan to become the world’s second largest film market. Yes, China is number two with a bullet, but Japan is hardly chopped liver. As an extra added benefit, studios do not have to debase their product or sell their souls to export films into Japan. Yet they seem to take perverse pleasure in kowtowing to Chinese Communist Party censors. However, the latest Japanese-centric installment of the X-Men franchise surely understood where its international bread would be buttered. Better than initial reviews gave it credit for, James Mangold’s simply titled The Wolverine is worth a look-see in theaters now.

As most guys between the ages of thirteen and fifty know, Logan is a mutant, whose uncanny healing powers were augmented with an adamantium skeleton and retractable claws. You cannot kill him, because he simply heals too fast, but you can definitely tick him off. At least that used to be the case. While visiting the deathbed of Yashida, the Japanese industrialist who knew Logan during dark days past, his healing powers are drastically impaired by Yashida’s strange physician, Dr. Green, who also happens to be a rather nasty mutant known as Viper.

At Yashida’s funeral, an attempt is made to kidnap Mariko Yashida, the granddaughter and surprise heir to the Yashida empire. Suspecting the yakuza assassins are in league with her somewhat disappointed father, Logan and Mariko go underground. However, the anti-hero mutant just isn’t shrugging off shotgun blasts to the gut like he used to. At least, he still has the claws and the temper, which are considerable. Nevertheless, he will need a bit of help from Yukio, a mutant orphan adopted by the Yashida family to serve as Mariko’s friend and confidant.

Wolverine works surprisingly well, because most of the time it is not operating as a superhero movie, but as a blend of the yakuza and ninja genres. No longer immortal, Logan follows the tradition of other noir gaijin hard-noses, like Robert Ryan in Sam Fuller’s House of Bamboo. The claws versus swords fight sequences are well staged and have real stakes. Unfortunately, the film makes a tactical mistake in the third act, veering into Iron Man territory not in keeping with up-close-and-personal hack-and-slashing tone it had so nicely established.

Regardless, The Wolverine has a real ace-in-the-hole in the person of supermodel turned thesp Rila Fukushima. As the trusted Yukio, she shows gobs of screen presence and wicked action chops. Frankly, many fans will want to see her and Logan walk the earth together, “like Caine in Kung Fu,” but the franchise seems to have different plans for the future (judging from the stinger-tease).

Tao Okamoto (another model) is also quite engaging as the dutiful Mariko, but probably Royal Shakespeare Company and Lost alumnus Hiroyuki Sanda is the most recognizable face after Hugh Jackman, bringing Shakespearean heaviness to the homicidal father, Shingen Yashida. Although clearly comfortable with the character by now, Jackman admirably digs into this grittier detour into mortality. On the other hand, Will Yun Lee (so good in Witchblade and the cool b-movie Four Assassins) is woefully under-utilized as ninja-protector Kenuichio Harada, while Svetlana Khodchenkova’s Viper is a bland standard issue super-villainess.

Just like leaving New York for Match Point helped reinvigorate Woody Allen, the Japanese setting ought to jump start the Wolverine sub-series. It should also herald Rila Fukushima’s arrival as an international action star. Had Mangold not been so tied to the big set pieces-go-boom superhero climax, The Wolverine could have really been an impressive fusion of Marvel mythology and Asian martial arts and action movie aesthetics. Despite the late adherence to convention, it is still consistently entertaining. Recommended for Marvel and yakuza genre fans, The Wolverine is still playing in theater nationwide, including the AMC Empire in New York.

LFM GRADE: B

Posted on August 26th, 2013 at 12:32pm.