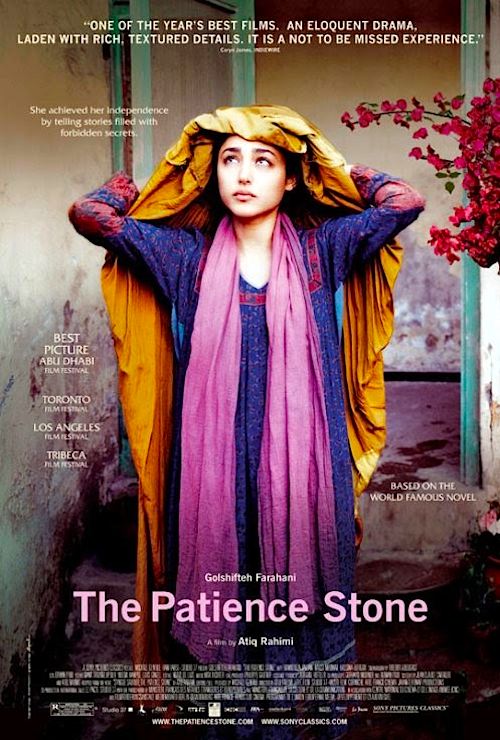

By Joe Bendel. For a woman in Afghanistan, an incapacitated husband is both dangerous and liberating. The unnamed man was never much of a husband, at least as westerners would understand the term, but he will finally become a good listener in Afghan expatriate Atiq Rahimi’s The Patience Stone, which opens this Wednesday in New York.

It was a loveless arranged marriage. Her grizzled old husband acquired her when she was really just a child. At least he was not around much during the early years of their marriage. Instead, he was off fighting whomever, only periodically returning to lord over her. Over time, they had two daughters, but they never “learned to love each other.” Yet, when a tawdry dust-up leads to a bullet in his neck and a subsequent coma, she loyally tends to her former tormentor.

Sending their children to live with their worldly aunt, the woman spends her days maintaining their battle-damaged home and watching over her comatose husband. She must keep him hidden from sight, lest the roving bands of warlords recognize her defenseless position. Unfortunately, a small contingent of soldiers eventually barges in, with the intent of forcing themselves on her. Understanding the perverse nature of her country’s misogyny, she claims to be a prostitute, causing most of them to lose interest. As her aunt explains, those sharing their virulent Islamist mentality take manly pride from raping virgins, but are repulsed by sexually experienced women.

However, the shy one eventually sneaks back, hoping to hire the woman’s services. She does not exactly agree at first, but they soon share intimate encounters on a regular basis. In fact, she starts to enjoy them, both as a sexually liberating experience and a passive aggressive salvo against her husband. She does indeed confess each assignation to him, as well as the rest of her deepest, darkest secrets. He has become her “Patience Stone,” the mythological vessel that retains all the sorrow the owner divulges, until it finally shatters.

However, the shy one eventually sneaks back, hoping to hire the woman’s services. She does not exactly agree at first, but they soon share intimate encounters on a regular basis. In fact, she starts to enjoy them, both as a sexually liberating experience and a passive aggressive salvo against her husband. She does indeed confess each assignation to him, as well as the rest of her deepest, darkest secrets. He has become her “Patience Stone,” the mythological vessel that retains all the sorrow the owner divulges, until it finally shatters.

What a lovely corner of the world this is. Women are treated like chattel, forced to wear burqas, and consequently blamed for the predatory behavior of men. Atiq’s film, based on his French language Prix Goncourt winning novel, quite boldly examines the pathological sexism of Islamist society. If it sounds vaguely homoerotic when the young soldier confides to the woman his commander puts bells on his feet and makes him dance in the evenings, it should. Atiq is rather circumspect in his handling of this issue, essentially using it to establish the woman’s sense of compassionate outrage. Fair enough, but there is only so much of that which can easily fit in to an intimate chamber drama such as Stone.

Essentially, Stone is a two-hander, but the second hand spends nearly the entire film in a persistent vegetative state. Fortunately, Golshifteh Farahani, the Iranian exile based in Paris (seen in Chicken and Plums and in Ridley Scott’s mullah-offending Body of Lies), is extraordinarily compelling as the woman, largely carrying the film on her shoulders. It is a profoundly vulnerable yet surprisingly sensual performance, likely to equally inspire her fans and outrage the theocrats in her Iranian homeland. Still, Mossi Mrowat has some quietly powerful moments as the young, naïve soldier.

True to the limits of the woman’s world, Stone has a two-set, four-character staginess that it just cannot shake loose. Nevertheless, it powerfully crystallizes all the anguish and rage pent-up inside exploited women like Atiq’s protagonist. He and Farahani might be exiles, but with Stone they vividly hold a mirror up to their respective societies. Recommended for those concerned about the state of women’s rights in the Islamic world and fans of Farahani, Patience Stone opens this Wednesday (8/14) at New York’s Film Forum.

LFM GRADE: A-

Posted on August 12th, 2013 5:31pm.