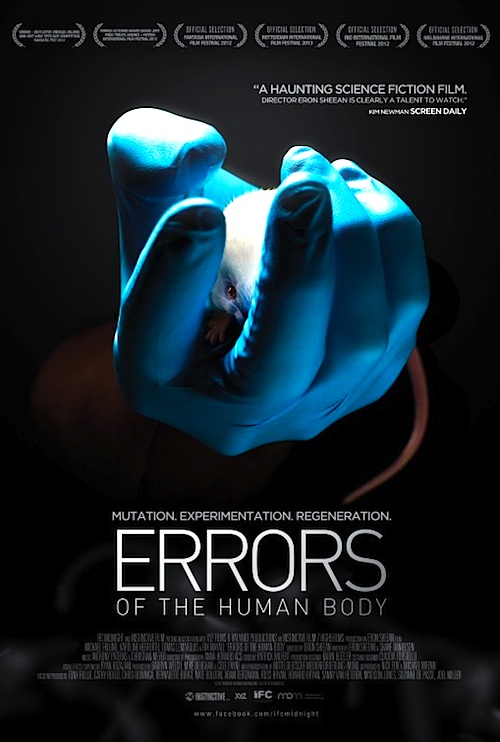

By Joe Bendel. Dresden was the center of East German research and technology. That did not make it any more fun than the rest of the country. Germany has since unified, but a visiting American scholar finds it still a rather sinister environment in Eron Sheenan’s Errors of the Human Body, which screens round midnights starting this Friday at the IFC Center.

Dr. Geoffrey Burton is known for once having a promising career. Forced out by his university, he has accepted a visiting scholar position at a non-profit German research institute. Fortunately, everyone there seems to speak English, including the British director, Samuel Mead, and Burton’s old flame, Dr. Rebekka Fiedler. They will reconnect, but Burton is not exactly good relationship material these days. He still obsessively calls his ex-wife and grieves over the infant they lost to a rare genetic disorder.

Understandably, Burton’s late son inspired his controversial research. Much to his surprise, it also motivated Fiedler’s recent work begun with her unstable former collaborator, Dr. Jarek Novak. She has had tremendous success regenerating salamanders, but has yet to apply it to anything with fur. However, Burton learns the salamander-looking scientist has secretly helped himself to her research. Gee, could all that sneaking around lead to a risk of infection?

Understandably, Burton’s late son inspired his controversial research. Much to his surprise, it also motivated Fiedler’s recent work begun with her unstable former collaborator, Dr. Jarek Novak. She has had tremendous success regenerating salamanders, but has yet to apply it to anything with fur. However, Burton learns the salamander-looking scientist has secretly helped himself to her research. Gee, could all that sneaking around lead to a risk of infection?

Errors is not a bad dark science fiction cautionary tale. Since it is set in a non-profit, we are spared the clichéd corporate demonization. It is also has an effectively chilly vibe. While the particulars of Dresden’s GDR history do not factor in the narrative, the city is certainly portrayed as a severe, impersonal locale. (Those intrigued by the Dresden’s role in East German techno-industrial history should check out Dolores L. Augustine’s fascinating book Red Prometheus.) The make-up and visual effects are quite presentable by genre standards, but Sheenan’s story is more character and concept driven.

Cult TV veteran Michael Eklund (whose credits include Fringe and Alcatraz) shows a talent for physically and emotionally self-imploding as Burton. In contrast, Karoline Herfurth is almost tragically Teutonic as Fiedler. Fortunately, Tómas Lemarquis dives into Novak’s Faustian scientist villainy with admirable enthusiasm. It is also amusing to see Rik Mayall (of The Young Ones) pop up as Mead, even if he plays it frustratingly straight.

If you want to see highly educated adults chasing mice around a lab Errors is the film for you. Frankly, the set-up is smarter than one might expect and the kicker has some bite. Recommended for genre fans, Errors of the Human Body begins a run of midnight screenings this Friday (4/19) in New York at the IFC Center.

LFM GRADE: B-

Posted on April 16th, 2013 at 8:23am.