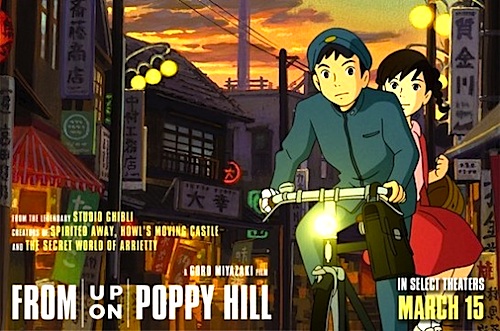

By Joe Bendel. Hosting the 1964 Tokyo Olympics completed Japan’s post-war rebirth. It would announce the arrival of a new democratic capitalist country on the world stage. However, as Japan prepares for the games in 1963, two high school students will come to terms with their past in Gorō Miyazaki’s From Up On Poppy Hill, the latest animated feature from Studio Ghibli (co-adapted from a manga favorite by the director’s legendary animator father Hayao), which screened as part of the 2013 New York International Children’s Festival, in advance of its Friday opening at the IFC Center.

Umi Matsuzaki is the perfect daughter, who studies diligently when she is not cooking and doing chores for her family’s boarding house guests. Unfortunately, her parents are not present to witness her hard work. Her mother is studying in an American graduate program and her father was lost at sea—or at least so she was told. Nevertheless, every morning she raises signal flags in hopes of guiding her sailor father home again. Her grandmother, siblings, and boarders appreciate all her hard work, but there is still a void in her life.

Suddenly, boys come into her life. Through an odd chain of events, the bemused Matsuzaki falls in with the rabble-rousing leaders of the Latin Quarter, a dilapidated fraternity house for her school’s male-dominated academic clubs. As the editor of the Latin Quarter’s newspaper, Shun Kazama has published his poems inspired by Matsuzaki’s flag-raising. Although the administration has decided to demolish their old building, the practical Matsuzaki becomes instrumental in their campaign to save the Latin Quarter. In the process, she and Kazama fall deeply in manga-anime style love. Unfortunately, Kazama discovers a secret link from their family histories that apparently changes everything.

At least the first third of Poppy is solely devoted to establishing Matsuzaki’s small corner of Yokohama and her various relationships with family, boarders, and fellow students. One could say not much happens, yet it is quite pleasant, in large measure due to the great likability of the virtuous but down-to-earth heroine. When Matsuzaki begins her sweetly awkward relationship with Kazama, while counseling his arrogant but well meaning friends, Poppy takes on the vibe of an upscale anime Archie comic. However, the past will continue to intrude on their reluctant melodrama.

Visually, Poppy is quite attractive, but its backgrounds and cityscapes are not nearly as lush as Ghibli’s two previous American releases, The Secret World of Arrietty and Tales from Earthsea. Still, it presents an appealing protagonist for younger girls, especially those who might feel self conscious about being studious or sensitive. Indeed, the fillm’s tone and characters are all quite endearing, propelled along quite nicely by Satoshi Takebe’s lightly swinging themes.

Reportedly, production on Poppy was interrupted but not derailed by the 2011 earthquake and tsunami, which adds a layer of significance to its story of perseverance and preservation. Comparatively small in scope and firmly rooted in reality, Poppy is like the Ghibli version of an Ozu film. Recommended for pre-teens and up who appreciate character driven animation, From Up On Poppy Hill opens this Friday (3/15) in New York, downtown at the IFC Center and uptown at the Elinor Bunin Munroe Film Center (with the Friday and Sunday screenings to be held in the Walter Reade instead).

LFM GRADE: B

Posted on March 14th, 2013 at 12:30pm.