By Joe Bendel. Don’t call Eluana Englaro the Italian Terri Schiavo. The latter case was scandalously misreported by the drive-by media, as civil libertarian Nat Hentoff passionately decried at the time. At least Englaro’s medical decisions were made by a loved one with no conflicts of interest. That certainly did not stop Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi from getting involved, thereby guaranteeing considerable drama. Director-co-writer Marco Bellocchio portrays the resulting media feeding frenzy through the eyes of three sets of fictional characters in Dormant Beauty (trailer here), which screens as a selection of Film Comment Selects 2013.

After a prolonged legal battle, Englaro’s father has transferred her to a private clinic in Udine, where her feeding will be discontinued. She really is in a persistent vegetative state. Berlusconi is not taking this lying down. Legislation has been introduced to save Englaro. Senator Uliano Beffardi intends to buck his party and vote against it. His reasons are personal. He once had to make a similar choice for his late wife, but his relationship with his pro-life daughter Maria has been strained ever since.

The Englaro case also hits close to home for the retired actress known simply as “Divine Mother.” She has preserved her beloved comatose daughter for years in hopes she will eventually wake-up. Meanwhile, Dr. Padillo is not following the case nearly as closely as his colleagues, but he is determined to prevent a recently admitted drug addict from killing herself.

Bellocchio applies a dramatic fairness doctrine to partisans on both sides, except the former PM. Did he really say Englaro looks healthy enough to “give birth to a son?” Afraid so. Look, say what you will about Berlusconi, but the man is never dull. Frankly, if Bellocchio had anything nice to say about him, he would probably be drummed out of every directors’ guild. In contrast, his depiction of the senator and his daughter is far from simplistic.

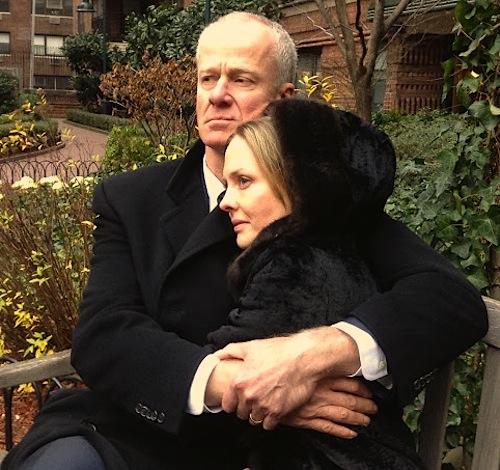

In fact, Maria is a wholly sympathetic character, who strikes up an unlikely romance with Roberto, the long-suffering brother of a wildly unstable pro-euthanasia demonstrator. Their bipartisan connection is one of the most appealing courtships seen on film in years. Likewise, her relationship with her father evolves in ways that are mature, believable, and satisfying.

Unfortunately, the other two story arcs are not nearly as rewarding. Divine Mother mainly seems to be in the film to compensate for Roberto’s creepy brother. Granted, she is played by the film’s biggest star, Isabelle Huppert, and valid reasons are established for cartoonish Catholicism. Nonetheless, the deck is clearly stacked against her. While her sequences are a tonal mishmash, they still most closely approach the operatic sweep of Bellocchio’s kind of awesome Vincere.

Considerably more engaging, the scenes shared by the doctor and his suicidal patient are well acted (by Bellocchio’s brother Pier Gregorio and Maya Sansa) and ring with honesty. They just feel like they were spliced in to further obscure Bellocchio’s personal position. That is a worthy impulse, but it would be unnecessary had he just focused on the Beffardis, whom most viewers will consider the primary subjects anyway.

Toni Servillo is absolutely fantastic as Beffardi, a decent man totally befuddled by the modest importance bestowed on him late in life. He never plays the part as a mouthpiece for a certain position, but as a world weary widower father. By the same token, Alba Rohrwacher demonstrates perfect pitch as the rebelliously devout Maria. She develops some palpable opposites-attract chemistry with Michele Riondino’s Roberto and gives the audience hope we can all grow and develop.

Dormant Beauty is sometimes a great film. There is some wickedly funny satire of the Italian senators that does not necessarily skew left or right, simply skewering the political class instead. Arguably, this is a case where less would have been more. Recommended for Servillo, Rohrwacher, and the compelling vibe of the Udine protests, Dormant Beauty is recommended for fans of Italian cinema and political drama when it screens today (2/20), Friday (2/22), and Sunday (2/24) at the Howard Gilman Theater as part of Film Comment Selects 2013.

LFM GRADE: B-

Posted on February 20th, 2013 at 1:14pm.