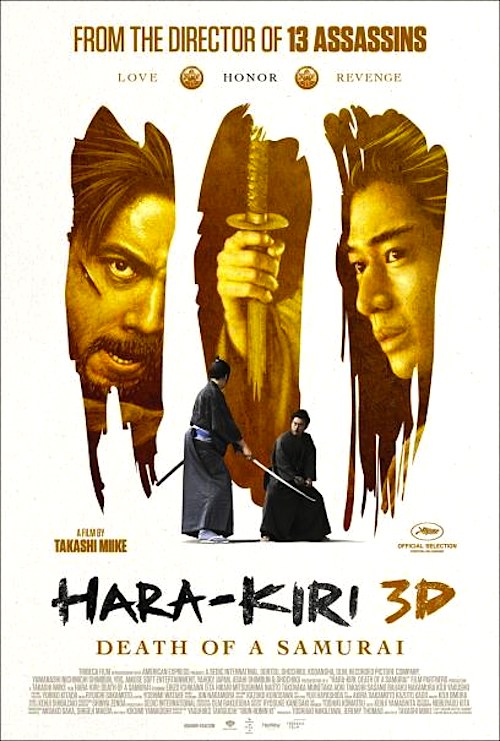

By Joe Bendel. Honor is not simply a matter of ritual and technicality, and samurai who have only known peace seem to have a tendency to forget the heart and spirit of their code. A ronin with a mysterious grievance intends to teach a noble house’s conceited retainers a hard lesson in Takeshi Miike’s Hara-Kiri: Death of a Samurai, now available on DVD and Blu-ray from New Video Group.

Yes, there is peace, but the Shogun’s devious maneuverings destroyed a once proud clan, leaving a glut of impoverished ronin (masterless samurai) at loose ends. The situation has given rise to a phenomenon known as “suicide bluffs,” where ronin ask for the use of the House of Ii’s courtyard to commit ritual seppuku in hopes they might receive a few coins and be sent on their way instead. Hanshirô Tsugumo has duly asked for such a favor from the head retainer Kageyu Saitou, but he seems to have his own agenda.

Hoping to dissuade him, Saitou tells him the pathetic story of the last ronin who came cold calling. Tired of indulging suicide bluffs, Saitou’s arrogant lieutenants forced the desperate young man to follow-through on his threat, in what quickly becomes a horrific display bearing little resemblance to any notion of honor. As it happens, Tsugumo already knows the gist of this tale. In fact, he is well acquainted with the sad young Motome Chiziiwa, as viewers learn in the next series of flashbacks.

Hoping to dissuade him, Saitou tells him the pathetic story of the last ronin who came cold calling. Tired of indulging suicide bluffs, Saitou’s arrogant lieutenants forced the desperate young man to follow-through on his threat, in what quickly becomes a horrific display bearing little resemblance to any notion of honor. As it happens, Tsugumo already knows the gist of this tale. In fact, he is well acquainted with the sad young Motome Chiziiwa, as viewers learn in the next series of flashbacks.

Based on the novel famously adapted by Masaki Kobayashi in 1962, Miike’s film is not called Hara-Kiri for no reason. About the first masterfully tense quarter is largely dedicated to Chiziiwa’s involuntary disembowelment. While the middle section somewhat suffers in comparison, Miike nonetheless provides all the necessary context to appreciate the first and third acts and fully establishes his central characters as sympathetic, flesh-and-blood figures – particularly Miho, the frail woman linking the two ronin together.

Indeed, Hikari Mitsushima is deeply affecting as the ill-fated (who isn’t in a Miike film?) Miho, a character lightyears removed from the all kinds of scary schoolgirl-cultist she brought to life in Sion Sono’s Love Exposure. Likewise, Eita is an aching model of pathos as Chiziiwa. However, Hara-Kiri really belongs to the two steely-eyed old dogs circling each other right from the beginning.

Traditional kabuki actor Ebizo Ichikawa (or Ebizo IX) appropriately simmers and seethes like a seriously hard-nosed, world weary swordsman with a point to make. He is the real deal, commanding every scene he appears in, which is quite the trick considering he is paired up against Kôji Yakusho, the international paragon of middle-aged badness, as Saitou. Once again, Yakusho brings gravitas and a sense of ruthlessness to the proceedings. While not nearly as crowd-pleasing as his lead role in Miike’s hit 13 Assassins, he makes the most of it.

Where Assassins delivers the hack-and-slash, Hara-Kiri offers foreboding and tragedy. Frankly, the latter was far truer to the heroics of the samurai era, which Ivan Morris described as the “nobility of failure.” However, the awesomely action-driven Assassins would have been a more logical candidate to be Miike’s first 3D film, yet that distinction belongs to Hara-Kiri. Regardless, it translates to 2D viewing just fine. A stately period production that is amply rewarding on multiple levels, Hara-Kiri is highly recommended for fans of samurai films and historical dramas in general. It is available at all online retailers from New Video Group.

LFM GRADE: B+

Posted on February 14th, 2013 at 12:38pm.