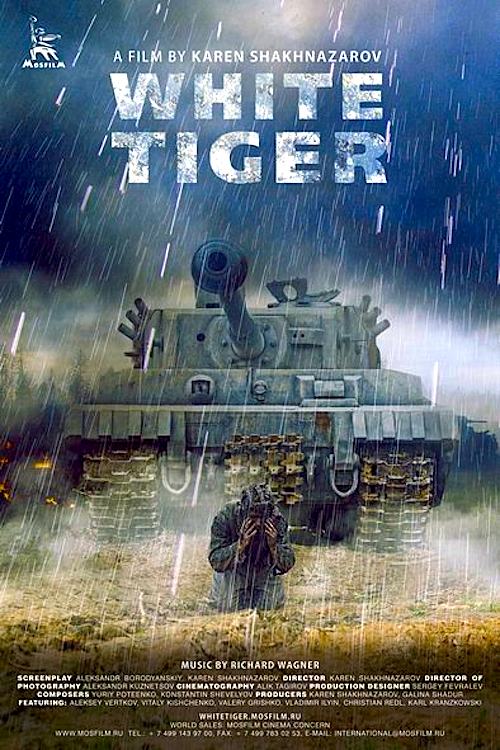

By Joe Bendel. Ivan Naidyonov could be called the tank whisperer. He seems to have the mystical power to commune with armored vehicles, but his environment is pure blood and guts. War is still war, except more so on the Eastern Front in Karen Shakhnazarov’s White Tiger, which Russia has chosen as their official submission for this year’s foreign language Academy Award.

Hoping to put the debacle of last year’s submission (Friend of Putin Nikita Mikhalkov’s universally panned Burnt By the Sun 2: Citadel) behind them, Russia has opted for another well-connected standard bearer in Mosfilm head Shakhnazarov. However, in this case the quality of the film and the director’s critical reputation represent a considerable step up.

Picking through the remains of a routed Russian tank division, soldiers find a charred driver who is somehow still breathing. Despite suffering severe burns to ninety percent of his body, the tank mechanic makes a full recovery, except for his acute amnesia. Rechristened Ivan Naidoyonov (“found Ivan,” roughly), he is sent back to the tank corps. He is a whiz at fixing and operating tanks, but he is a little spooky. Naidyonov claims tanks speak to him and even starts praying to the “God of tanks” enthroned in the big garage in the sky. Yet he is just the man to track down and destroy the white German super tank that seemingly materializes out of nowhere to wreak destruction on blindsided armored columns.

For Naidyonov it is personal. The spirits of the destroyed tanks have spoken to him about the White Tiger. So perfect are its maneuvers, he is convinced its crew is “dead.” He can sense it before it appears and it seems to be hunting specifically for him.

For Naidyonov it is personal. The spirits of the destroyed tanks have spoken to him about the White Tiger. So perfect are its maneuvers, he is convinced its crew is “dead.” He can sense it before it appears and it seems to be hunting specifically for him.

White Tiger might sound like Life of Pi in a tank, but at every battlefield juncture, Shakhnazarov chooses grit over woo-woo. Everyone thinks Naidyonov is nuts, but they secretly suspect there might be something to him – particularly Major Fedotov, the counter-intelligence officer in charge of the hunt for the White Tiger. The resulting vibe is like The Big Red One as re-written and Russified by Melville.

With his studio’s resources at his disposal, Shakhnazarov stages some fantastic tank battles, vividly conveying their force – and also their limitations. During the first two acts, White Tiger is a completely original, totally engrossing war film. Strangely, though, the final third is largely dominated by completely unrelated scenes of the German surrender and Hitler’s ruminations in the face of defeat. It is like White Tiger won the war, but lost the peace. Still, since it is a war movie, the former is more important.

When Naidyonov and his obsession are center stage, White Tiger is genuinely riveting, with a good measure of credit due to its primary leads. Aleksey Vertkov is perfect as Naidyonov. Refraining from distractingly ticky or showy behavior, he is compellingly “off” in a way that could believably be recycled back into the Soviet war machine. Even though in reality his character would have probably been purged halfway through the film, Vitaliy Kishchenko’s work as the square-jawed Fedotov is similarly smart, understated, and intense.

It is hard to understand why Shakhnazarov would establish such a powerfully focused mood, only to break it up down the stretch. Still, White Tiger boasts two excellent performances and some impressive warfighting sequences, which is more than many of its fellow contenders can offer. Academy voters certainly love them some WWII, so it is probably worth keeping an eye on. Shakhnazarov has also had American distribution for past films like Vanished Empire, so White Tiger should have international legs. Regardless of its odd flaws, it is a film of considerable merit that ought to find an audience.

LFM GRADE: B

Posted on November 9th, 2012 at 2:20pm.