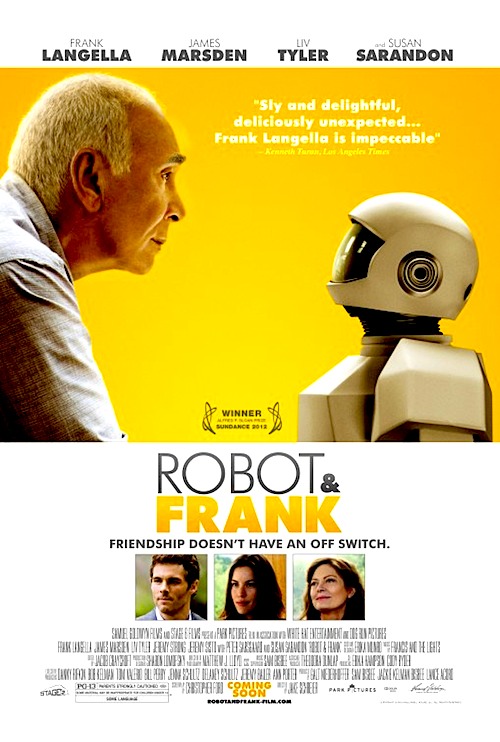

By Joe Bendel. Humans anthropomorphize. It is a very human thing to do, especially for objects that move on their own accord. One retired burglar will find himself doing just that with his assisted living droid in Jake Schreier’s very near future Robot & Frank, which opens this Friday in New York.

Frank Weld did not exactly get away scot free, but he is still living out his golden years in complete liberty. Unfortunately, his memory lapses are getting progressively worse. His establishment son Hunter is worried, because concern is what he does best. In contrast, New Age daughter Madison sees no evil when she calls in from exotic backwaters like Turkmenistan. Hoping to reverse his father’s slide, Hunter brings him a robot to help with the household chores and keep the difficult senior on a regular schedule.

Of course, Old Man Weld initially thinks little of his robot helper, nor does his kneejerk Luddite daughter. However, when the former burglar realizes the robot has a knack for things like lock-picking, he has a dramatic change of heart. He also has a perfect target: the oily hipster overseeing the conversion of his beloved library into some sort holographic monstrosity.

Of course, Old Man Weld initially thinks little of his robot helper, nor does his kneejerk Luddite daughter. However, when the former burglar realizes the robot has a knack for things like lock-picking, he has a dramatic change of heart. He also has a perfect target: the oily hipster overseeing the conversion of his beloved library into some sort holographic monstrosity.

Having a purpose seems to do wonders for his mental state. He even starts seriously putting the moves on Jennifer, the librarian he always tentatively flirted with. Needless to say, though, the caper turns out to be a bit more complicated than expected.

Essentially, R&F is an intimate character study with some decidedly gentle SF elements (despite winning the Alfred P. Sloan Award for addressing themes of science and technology in indie film at this year’s Sundance); in other words, neither Frank the character (who is quite well read) nor Schreier is interested in exploring the implications of the singularity, at least not in this film. Yet though Schreier’s style is never all that showy, his restraint serves the material rather well. In fact, a late revelation packs considerable punch precisely because of its understated treatment.

Likewise, Frank Langella never overplays his hand, conveying his namesake’s vulnerabilities and self-doubt in quiet but effective moments. James Marsden does his best work perhaps ever (which is not saying much, with Lurie’s Straw Dogs remake relatively fresh in mind) as the understandably exasperated son. As Jennifer the librarian, Susan Sarandon makes the most of what initially appears to be little more than an extended cameo, but unfolds into something much more significant. Even Liv Tyler is not totally awful as daughter Madison (though “good” would still be pushing it).

Smartly written by Christopher D. Ford, R&F leaves viewers without complete closure, in a way that will ring true for families that have gone through similar experiences as the Welds. A sensitive, only slightly speculative film, Robot & Frank is easily recommended for general audiences (particularly librarians, robotics engineers, and thieves) when it opens this Friday (8/17) in New York at the Angelika Film Center downtown and the Paris Theatre uptown.

LFM GRADE: B+

Posted on August 14th, 2012 at 10:00am.