[Editor’s Note: the post below appears today on the front page of The Huffington Post.]

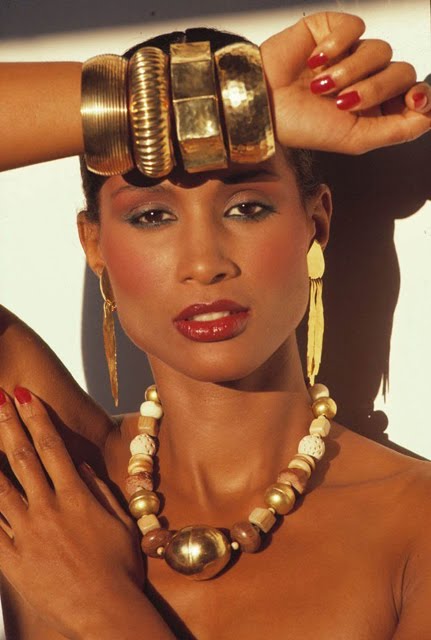

By Govindini Murty. They’re among the most iconic faces of the second half of the twentieth century. Isabella Rossellini, Beverly Johnson, Paulina Porizkova, and their supermodel sorority helped to shape public perceptions of beauty and womanhood at a time of rapid expansion in the mass media. Their faces graced thousands of magazine covers and they were role models to millions of young women.

But was the rise of the supermodel a sign of female empowerment, or of female objectification?

About Face: Supermodels Then and Now, an insightful new documentary by director and photographer Timothy Greenfield-Sanders available on HBO on-demand through September 3 and HBO Go through 2013, interviews sixteen of these supermodels about the true nature of beauty in an age of consumerism and mass media.

As alluded to in About Face, the irony that underlies the modeling profession is that it should lead to both the empowerment and objectification of women. On the one hand, the mass distribution of images of female models through fashion magazines, ads, and other media in the past century has led to women becoming quite literally more visible in today’s world – with that visibility being an affirmation of their femininity and right to exist as women in the public sphere. In contrast to this, from the Puritans to the Taliban, misogynistic societies through history have restricted sensual or beautiful images of women as a prelude to denying their basic right to participate in public life, citing women’s beauty as a “corrupting” influence on social morality. The predominance of beautiful images of women in Western culture has thus affirmed the broader right of women to exist in public as feminine and not as neutered beings.

On the other hand, modeling has also had the effect of objectifying women by focusing on external surfaces, and at times unnatural standards of beauty. In About Face, Isabella Rossellini asks of the pressure for women to undergo plastic surgery: “Is this the new foot-binding? It’s misogyny to say that older women are unattractive.” Objectification can also lead to racism by dehumanizing people and imposing narrow standards of ‘beauty’ or ‘normalcy.’ Model and agent Bethann Hardison describes in About Face trying to book African-American models for runway shows in the ’70s and ’80s, only to be told by the casting agents that such models weren’t their “aesthetic.” As Hardison explains “‘Aesthetic’ is borderline for racist.”

I spoke with director Timothy Greenfield-Sanders about some of these issues at the LA Film Festival’s screening of About Face. The interview has been edited for length.

GM: What drew you to these ladies? I know you met them initially at a party in New York, but what did you find so magical about them?

TGS: I think when I met them at that party … I immediately got a sense of how smart they were. You know, the cliché is that you either have brains or beauty, but you don’t have both. Well, they seemed to have both. It really makes it an interesting film. And I thought that people weren’t aware of that. I have two young daughters who knew who they were. But many young people today who are so interested in fashion, they don’t know the history of it and of these iconic women.

GM: What has changed about modeling? You mentioned in the screening that these models were so unique, whereas today the models and their careers seem more transient. Why is there this disparity today versus back then?

TGS: I think that it was a smaller world then. I think there was a warmer relationship between the models and the designers and even the businesspeople involved. It was not so cut-throat and not so corporate. And I think today it’s just big business and big money, and I don’t think the human relationship is there as much. I think it’s very changed.

GM: Do you think a big part of that is the issue of covers – that the actresses are taking over magazine covers?

TGS: Yes.

GM: It’s such a striking change. What has that done to the morale of the models? Does it make a big difference behind the scenes?

TGS: I’m not sure I can answer that because it’s not my world, exactly. But I know certainly it was huge in those days to have covers, because covers were the definition of success. And the cover of Vogue was the ultimate success. So when Beverly Johnson got on the cover of Vogue – the first black woman to do so [in August, 1974], that was a big deal. And today – that doesn’t happen for models.

GM: I thought it was very interesting what Dayle Haddon said that it wasn’t just that she thought she was the prettiest – in fact she didn’t quite fit into the physical type that was popular at the time, but that she brought something else to the picture.

TGS: She brought something else. And Dayle Haddon had to struggle because she wasn’t the look of the moment. She was a very smart woman and she figured out a way to add something more to the picture.

GM: Do you think the reason that those models from that era were so powerful – we’re talking the ’70s and ’80s, was because they were often muses for the designers they were working with?

TGS: Yes, exactly.

GM: I think of Yves St. Laurent and models like Khadija Adams, or even Catherine Deneuve in the ’60s who was dressed by St. Laurent for Belle de Jour. I think of Calvin Klein and Brooke Shields, they were so intimately tied together. Continue reading LFM’s Govindini Murty at The Huffington Post: Supermodels and True Beauty: A Conversation with Timothy Greenfield-Sanders of HBO’s About Face