By Joe Bendel. Robert Flaherty is considered the father of documentary filmmaking. With Nanook of the North, he not only launched the modern documentary film genre, he also introduced the ethical questions that continue to dog non-fiction filmmakers. The legacy of Flaherty and the relatively small handful of films he actually completed is explored in Mac Dara Ó Curraidhín’s A Boatload of Wild Irishmen, which screens as part of this week’s Robert Flaherty series at the Anthology Film Archives.

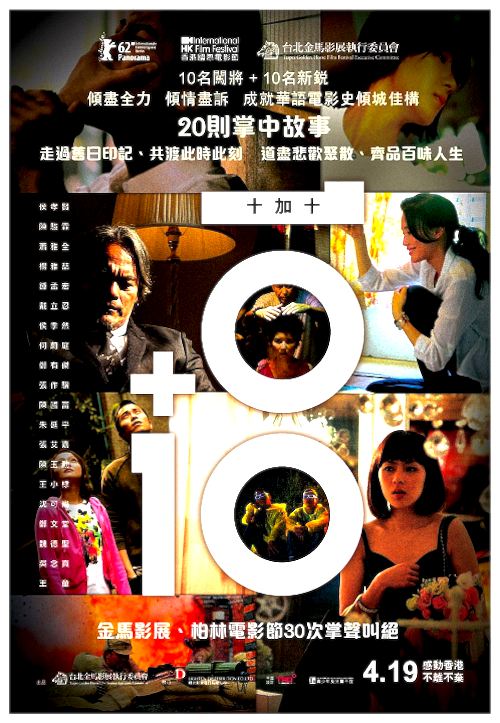

Boatload opens with the dramatic closing scene of Flaherty’s masterwork, Man of Aran (see above). Struggling against a powerful surge, the salt-of-the-earth fishermen fight their way to shore. Flaherty did not just happen to be in the right place at the right time to capture the action, however. He either sent them out into the roiling tide, or they volunteered to go. Accounts differ, but everyone seems to agree the money Flaherty was offering played a role. Even then it would not have been much by Hollywood standards, but to residents of the Ireland’s hardscrabble Aran Island, it was significant.

Indeed, Boatload’s various on-screen commentators make it clear that staging scenes was a major part of Flaherty’s working method. Opinions regarding the Irish-American filmmaker appear to be mixed at best amongst contemporary Aran Islanders and Irish film scholars. However, such criticism of Flaherty’s authenticity is largely based on current standards of documentary filmmaking, which are rather selectively applied.

Ó Curraidhín paints a picture of Flaherty as more of an adventurer than an auteur. Rather than Jacob Riis, P.T. Barnum would be better considered his forerunner. So what if he did stage a scene, or a dozen? It was for the sake of a good show. In contrast, when recent documentaries like Gasland play veracity games, it is far more serious, because they are advocacy broadsides, arguing for punitive measures targeting specific companies and industries.

Clearly, Flaherty was not a take-only-pictures-leave-only-footprints kind of documentarian, as the interview with his Inuit granddaughter fully attests. Yet the Samoans still regularly screen Flaherty’s Moana, enjoying the sight of their ancestors on-screen, even if the episodes they are recreating were from generations before them. Obviously, the point is that there are many different ways to come to terms with Flaherty’s small oeuvre.

Refraining from passing judgment on Flaherty, Boatload emphasizes his larger than life persona and the lasting audience for his films. Ultimately, the people have spoken. Considerably more film patrons will attend screenings of Flaherty’s films this year than those of silent western superstar Tom Mix by a wide margin, a trend that continues this week at AFA. Informative and evenhanded, A Boatload of Wild Irish is a satisfying survey of Flaherty’s work and controversies. Recommended for those who enjoy films about filmmaking, it screens this Saturday through next Monday (7/7-7/9) in New York at the Anthology Film Archives.

LFM GRADE: B

Posted on July 3rd, 2012 at 2:41pm.