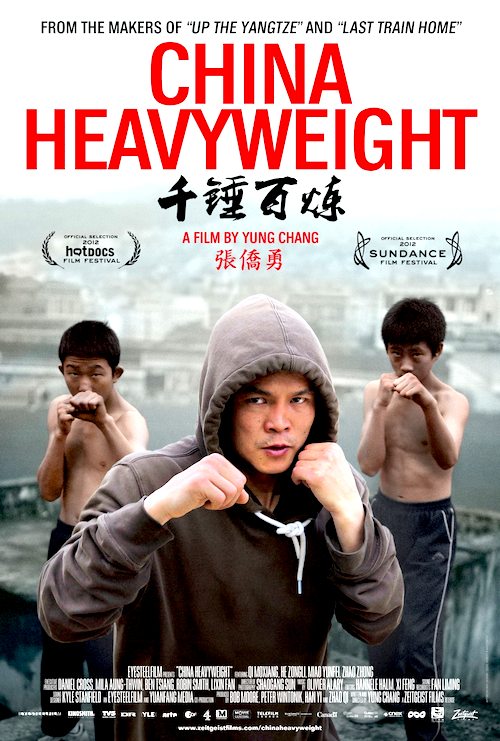

By Joe Bendel. Life in China must be improving. They now have round-card girls. Decades ago, Mao banned Olympic-style boxing on the grounds it was too western and excessively violent. He then launched the Cultural Revolution. Legalized in 1986, the Chinese boxing authorities are now taking a long view, recruiting potential Olympians at the middle school level. Yung Chang follows a contender turned coach and two of his fighters in China Heavyweight, which opens this Friday in New York at the IFC Center.

Boxing is an attractive alternative to working in the tobacco fields for many of the students in the Sichuan countryside. The sport has become a way of life for Coach Qi Moxiang. He recruits young boxers, both boys and girls, and directly oversees their training. He is tough, but popular with his charges.

At first, Chang’s primary POV figures appear to be He Zongli and Miao Yunfei, two boxers about to graduate to the regional level of competition. We see a fair amount of training and the mean condition of life in the province that they hope to escape. However, Heavyweight kicks into narrative gear about halfway through, when Qi decides to return to the ring to face a Japanese belt-holder. Suddenly, there is a traditional underdog boxing story unfolding in Sichuan.

At first, Chang’s primary POV figures appear to be He Zongli and Miao Yunfei, two boxers about to graduate to the regional level of competition. We see a fair amount of training and the mean condition of life in the province that they hope to escape. However, Heavyweight kicks into narrative gear about halfway through, when Qi decides to return to the ring to face a Japanese belt-holder. Suddenly, there is a traditional underdog boxing story unfolding in Sichuan.

Heavyweight is highly attuned to the economic disparities of contemporary China as well as the conflicts between tradition and the drive to modernize. However, Chang largely overlooks Sichuan’s recent tragic history. Rocked by an earthquake in May of 2008, anger boiled over at the local authorities for allowing the shoddy construction practices that acerbated its deadly toll. Sichuan could use a champion, but that might not be in the interests of the vested establishment.

Still, Chang has a good handle on the conventions of boxing movies, capturing some dramatic ringside action. There is even a scene of Qi’s boxers running up a series of ancient steps that echoes a certain film from 1976. He and cinematographer Sun Shaoguang also convey the harsh and lonely beauty of the surrounding terraced landscape. Viewers get a sense of the milieu, but besides Qi, the boxers’ personalities are not so strongly delineated (He is the shy one, while Miao is the slightly more confident one).

Shifting from an observational doc into old fashioned sports story, Heavyweight becomes more engaging as it goes along. The development of organized boxing post-Maoist insanity is a story worth telling, but as a socio-economic investigation, it is not nearly as telling as a raft of recent depressing Chinese documentaries, such as Zhao Liang’s jaw-dropping expose Petition, or the uncomfortably intimate Last Train Home, helmed by Heavyweight co-executive producer Lixin Fan. Oddly recommended more for the audience of HBO’s Real Sports than for serious China watchers, China Heavyweight opens this Friday (7/6) at the IFC Center.

LFM GRADE: B-

Posted on July 3rd, 2012 at 2:43pm.