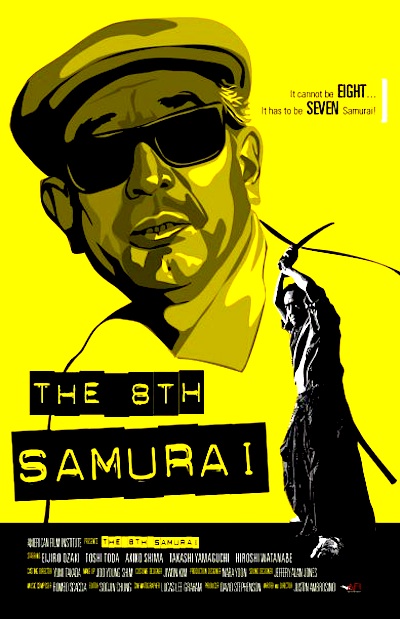

By Joe Bendel. Ho Kwok-fai is not living in a random universe. Accidents happen for a reason: money. He would know. He is the mastermind behind a team of “accident choreographers.” Unfortunately, they have apparently attracted the wrong sort of attention from a competitor in Accident (trailer here), Soi Cheang’s moody thriller produced by HK action legend Johnnie To, which releases this week on DVD and Blu-ray from Shout Factory.

Though not quite as Rube Goldbergian, Ho’s team are like a Final Destination movie unto themselves. Just ask the Triad boss in the opening sequence, while you can. “The Brain” runs the show with tick-tock precision, but a dark cloud seems to hang over their latest gig. “Uncle” starts to show signs of dementia and the necessary rain will not come. Then the wheels come totally off.

Going underground, Ho starts surveilling an insurance executive he suspects played a part in the disastrous non-accident. Already haunted by his wife’s fatal auto crash, his psyche will sink to some pretty low places. Rather than a standard hitman-on-the-run film, Accident treads a more existential path, in the tradition of Coppola’s The Conversation (granted, it is not exactly in the same league).

In the years since To’s Election epic most of what American audiences have seen of Louis Koo were romantic or comedic features, like Mr. and Mrs. Incredible, Magic to Win, and All’s Well Ends Well 2012, 2011, 2010, and 2009. Nonetheless, he shows plenty of screen grit in Accident, brooding like mad, yet getting stone cold medieval when necessary. As a bonus, Lam Suet, To’s regular comic relief specialist, brings his usual energy, but plays Ho’s stout but not shticky henchman “Fatty” with considerable restraint.

Viewers who have seen a lot of Hollywood-produced thrillers will probably be downright shocked by Accident, precisely because of their preconditioning. Indeed, Cheang is willing to take it in a direction studio filmmakers never would, which is cool. Of course, knowing it is produced by To and his Milkyway Image team is something of a seal of approval in and of itself. Enthusiastically recommended for fans of noir thrillers and HK cinema, Accident is now available on DVD at online and quality brick-and-mortar retailers everywhere.

LFM GRADE: A-

Posted on June 13th, 2012 at 10:37am.