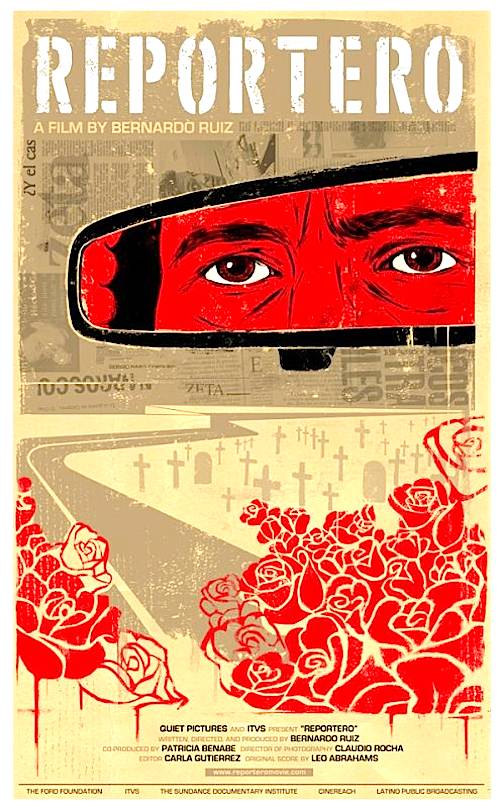

By Joe Bendel. For years, Mexico’s best journalism has been done in Tijuana. Frankly, with the rise of the drug cartels’ power, Tijuana might be the only place in the country where real journalism is practiced with conviction. However, the staff of the resolutely independent news weekly Zeta has paid a heavy price for their journalistic integrity. Bernardo Ruiz documents their dangerous mission covering the drug lords and the crooked politicians abetting them in Reportero (trailer here), which screens as part of the 2012 Human Rights Film Festival in New York and also at The Los Angeles Film Festival.

By Joe Bendel. For years, Mexico’s best journalism has been done in Tijuana. Frankly, with the rise of the drug cartels’ power, Tijuana might be the only place in the country where real journalism is practiced with conviction. However, the staff of the resolutely independent news weekly Zeta has paid a heavy price for their journalistic integrity. Bernardo Ruiz documents their dangerous mission covering the drug lords and the crooked politicians abetting them in Reportero (trailer here), which screens as part of the 2012 Human Rights Film Festival in New York and also at The Los Angeles Film Festival.

Based on the experience of Zeta staffers, one could justifiably ask if Mexico ever had a free press, as such. Founded to investigate the widespread corruption of the long ruling socialist PRI party, Jesús Blancornelas made a crucial decision to print the newspaper on the American side of the border. This would be more expensive, but far more secure. While the PRI is now temporarily on the outs, the drug traffickers have become even more proactive buying-off or outright intimidating journalists. Indeed, Zeta has suffered its share of assassinations, including very nearly their founder, Blancornelas.

Ruiz adopts old school investigative journalist Sergio Haro as his primary POV figure. No stranger to death threats, Haro has fearlessly raked the muck of Baja California. Though a family man, he comes across as an existential champion of the underclass, who nonetheless needles the leftist PRI every chance he gets. While not the most animated screen presence, Haro clearly walks the walk. His stories should be considered blockbusters, but the guilty continue on, with evident impunity.

Ruiz’s dry observational style tries its best to drain all the sensationalism out of the film, but Zeta’s four-alarm headlines speak for themselves. Indeed, the crusading publication’s war stories are exactly that. Their scoop concluding the film is quite a jaw-dropper, but it is the memorial to one of two fallen comrades that really says it all.

It is nearly impossible to consider Mexico a functional state after viewing Ruiz’s profile of Zeta. Fascinating but deeply scary stuff, Reportero is a bracing tribute to the new weekly’s principled journalists (and the staff of a short lived daily paper Haro founded in between his Zeta stints). While it is an ITVS production destined for PBS broadcasts, it is well worth seeing the longer festival cut, because these details are devilishly important. Recommended for anyone concerned about press freedoms or the social-political health of our southern neighbor, Reportero screens at The Human Rights Film Festival next Thursday (6/21), Friday (6/22), and Saturday (6/23) at the Walter Reade Theater and tonight (6/18) at The Los Angeles Film Festival.

LFM GRADE: B

Posted on June 18th, 2012 at 4:54pm.