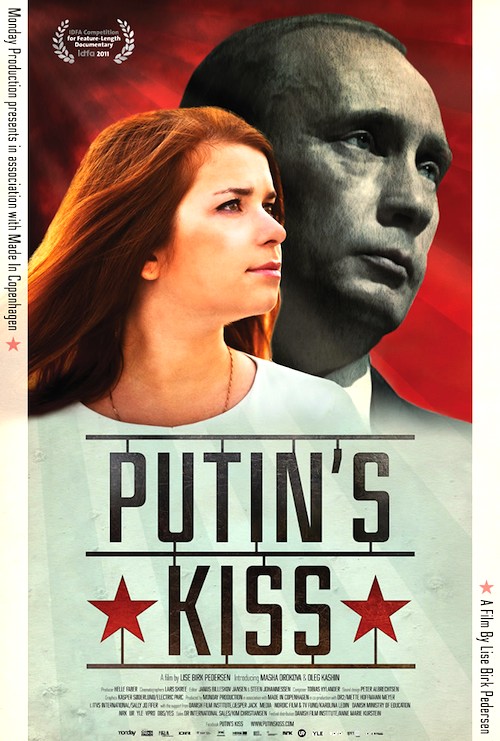

By Joe Bendel. Perhaps nothing signified the all-encompassing totalitarianism of National Socialism better than the Hitler Youth. Likewise, the Komsomol, or Communist Union of Youth, was emblematic of Soviet oppression. According to independent observers, the names are different, but the Komsomol has risen again in the guise of Nashi, a Kremlin-backed youth group fiercely loyal to the current Russian Prime Minister. Though once a prominent spokesperson for the group, one young woman began to understand the realities of the regime she served. Lise Birk Pedersen documents her fascinating story in Putin’s Kiss, which opens this Friday in New York.

Masha Drokova was an ambitious student who believed the government’s propaganda. She joined Nashi, rocketing up the ranks after she famously kissed the titular Russian strongman on state television. She became a national media figure and dogged foe of Putin’s democratic critics. However, her interest in journalism brought her into contact with independent reporters, like Oleg Khasin.

While remaining committed to Nashi, she found she enjoyed the open and robust debates with her new friends. Unfortunately, this did not bode well for her standing within the Putin Youth. When Khasin is brutally beaten thugs considered by everyone except the most willfully blind Nashi loyalists to be acting at the behest of the Kremlin or its allies, Drokova reaches a crossroads.

While remaining committed to Nashi, she found she enjoyed the open and robust debates with her new friends. Unfortunately, this did not bode well for her standing within the Putin Youth. When Khasin is brutally beaten thugs considered by everyone except the most willfully blind Nashi loyalists to be acting at the behest of the Kremlin or its allies, Drokova reaches a crossroads.

Only in her early twenties, Drokova is still at an age when peer pressure has very real consequences. To her credit, she stood by her injured friend, joining those demanding a proper inquiry, at no little risk to her well being. Yet she does not repudiate her time serving Putin’s interests. As real journalists say, this story is still developing. Shrewdly, Pedersen never tries to impose a preset narrative, scrupulously recording the messy ambiguities of Drokova’s circumstances instead. Indeed, that is what makes the film so fascinating. Rather than a neat and tidy epiphany, we watch her reservations and doubts begin to stir.

Frankly, Drokova is not yet a fully mature adult, which can lead to viewer frustration with her as their POV protagonist. However, it is important to remember this is exactly why Nashi recruited Drokova and those like her. Indeed, Pedersen conveys a frighteningly vivid sense of Nashi’s reach and influence. After watching Kiss, it is impossible to accept claims that the group is a nonpartisan service movement.

Kiss is an important film that shines an international spotlight on Putin’s youthful enforcers. Pedersen rakes a fair amount of muck, while capturing a very personal story with wider political implications. Mostly scary and only occasionally encouraging, it is highly recommended for viewers concerned and interested in the state of the world. It opens this Friday (2/17) in New York at the Cinema Village.

Posted on February 15th, 2012 at 10:35am.