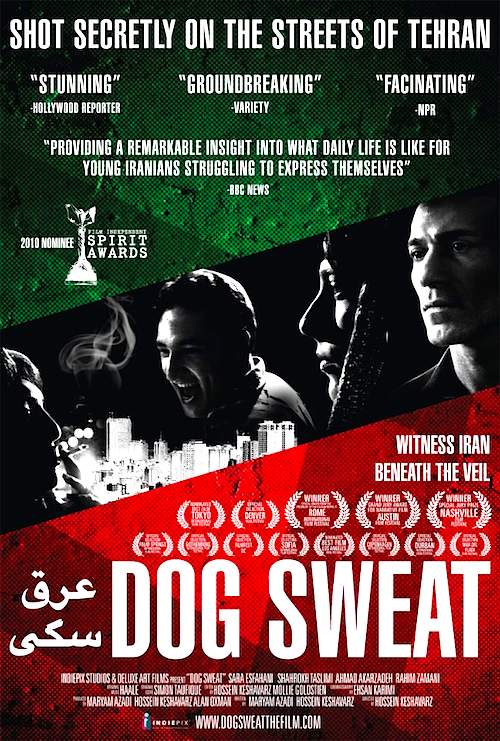

By Joe Bendel. They said Prohibition could never work, because you cannot “legislate morality.” Try telling that to Iran’s Islamist government while you’re looking for a bottle of spirits in Tehran. Of course, a bottle can be found on the black market, but the risks are considerably higher and the costs are far greater than in New York of the 1920s. Still, a group of young Iranians keep the party going as best they can until the messy realities of life overwhelm them in Hossein Keshavarz’s Dog Sweat, which screens tonight during the 2011 New Orleans Middle East Film Festival.

Massoud and his cronies love their illegal hooch, or “dog sweat” as they call it. He sobers up quickly though, when his mother is critically injured by a driver who cannot afford to pay “blood money.” He is in no mood to hear how it is all one of the trials of life mandated by God, considering it more a test of Iranian society, which it fails miserably. Hooshang and Homan also enjoy the Tehran nightlife, but once the former gives into his wealthy family’s demands that he wed, the once constant companions no longer spend time together. Sweat never explicitly states why, but the implication is impossible to miss.

Hooshang’s new wife Mahsa also makes sacrifices to conform to the life expected of her. A talented underground vocalist, she must give up her forbidden musical career for the sake of married respectability. In contrast, Katie is involved in a more conventional love triangle, balancing the attentions of the impetuous Bijan and the older well-to-do Mehrdad, who also happens to be married, to her cousin. Held a virtual captive by her controlling mother, Katie bristles at the freedom allowed to her brother Dawood. Yet, he still cannot manage to find a place to be alone with his prospective girlfriend, Katie’s best friend Katherine.

Hooshang’s new wife Mahsa also makes sacrifices to conform to the life expected of her. A talented underground vocalist, she must give up her forbidden musical career for the sake of married respectability. In contrast, Katie is involved in a more conventional love triangle, balancing the attentions of the impetuous Bijan and the older well-to-do Mehrdad, who also happens to be married, to her cousin. Held a virtual captive by her controlling mother, Katie bristles at the freedom allowed to her brother Dawood. Yet, he still cannot manage to find a place to be alone with his prospective girlfriend, Katie’s best friend Katherine.

Obviously produced without the official sanction of the Iranian film authorities, Sweat has much to say about gender inequality and the repression of sexual identity in contemporary Iran. It also addresses the lack of free artistic expression and the judgmental severity of religious fundamentalism. To top it all off, Mahsa’s mother Forough takes a pilgrimage to Karbala in Iraq, Iran’s traditional rival, experiencing for the first time in her life a feeling of peace and spiritual fulfillment there.

Given such themes, it is a bit of a surprise the undeniably bold Sweat does not feel heavier. Indeed, some decidedly tragic events occur and nobody (aside from Forough) is ever really happy, but Keshavarz and co-writer-producer Maryam Azadi (who both served as associate producers on his sister Maryam Keshavarz’s Circumstance) never revel in the misery and meanness. Instead, he shows it all to viewers in a straightforward, direct manner and then rotates his focus to the next set of characters. Although a product of necessity, the guerilla vérité-style production gives the film a raw, intimate look that nicely fits the subject matter.

In fact, it is a tribute to the ensemble cast that we do not consider them actors, but authentic people, perhaps in some ominous version of Real World Tehran. Still, Shahrokh Taslimi’s animal intensity as Massoud stands out fiercely.

When watching Sweat one has the sensation of sharing in the lives of this generation of young professional Iranians, who navigate a world that is half underground and half above-board. Granted, it is not perfectly executed. Keshavarz leaves a lot of messy lose ends and unresolved questions, but he definitely takes viewers into the world and heads of these acutely human characters. Highly recommended, Sweat screens tonight (12/14) during the New Orleans Middle East Film Festival, as part of a slate of films varying widely in terms of quality and political sophistication.

Posted on December 14th, 2011 at 12:33pm.