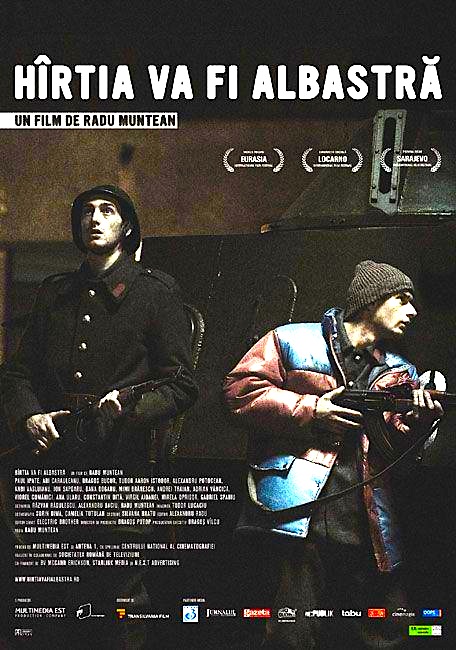

By Joe Bendel. In 1989, the Romanian military received the orders all soldiers serving behind the Iron Curtain dreaded most. They were commanded to fire upon their fellow countrymen. Some did so, to an extent, but many more sided with the Revolution. Radu Muntean captures the chaotic anarchy in the hours immediately following the fall of Ceaușescu in his distinctly anti-heroic The Paper Will Be Blue (trailer here), which screened as part of a Muntean retrospective on the closing night of the Sixth Annual Romanian Film Festival, co-presented by the Romanian Cultural Institute and the Film Society of Lincoln Center.

By Joe Bendel. In 1989, the Romanian military received the orders all soldiers serving behind the Iron Curtain dreaded most. They were commanded to fire upon their fellow countrymen. Some did so, to an extent, but many more sided with the Revolution. Radu Muntean captures the chaotic anarchy in the hours immediately following the fall of Ceaușescu in his distinctly anti-heroic The Paper Will Be Blue (trailer here), which screened as part of a Muntean retrospective on the closing night of the Sixth Annual Romanian Film Festival, co-presented by the Romanian Cultural Institute and the Film Society of Lincoln Center.

Blue’s flashback format tells viewers right up front this night will end badly. Muntean then rewinds a few hours to show how events reached this point. Though Ceaușescu has been deposed, the military is not sure what to make of it. The revolutionaries have seized the television studio and many officers and enlisted men have volunteered to defend it from Communist Loyalists – or as the call them, terrorists. If you are wondering how to tell one side from the other, then you have just pinpointed the crux of Blue.

Militia (state copper) Lt. Neagu’s armored squad vehicle has been assigned to patrol a sleepy suburb well away from the action. However, one of his men from a politically connected family, Costi Andronescu, has deserted to join the forces defending the TV station. Fearing he will be disciplined for the actions of his subordinate, Neagu and his men venture into the maelstrom, hoping to bring back Andronescu in time for morning roll call. As they careen through the streets of Bucharest, allegiances become increasingly confused.

With its gritty docudrama-style and Kafkaesque absurdity, Blue bears many of the hallmarks of the so-called Romanian New Wave. However, there is no slack in this picture. It is tight and tense, holding a firm grip on viewers even though they know exactly where it ends. Muntean vividly captures both the claustrophobia within the armored car, and the disorienting commotion unfolding outside. The film also resists easy political labels, revisionist or otherwise, but as is often the case in the Romanian Wave, bureaucracy and authority figures take a real skewering.

Adi Carauleanu is fantastic as the world-weary but compulsively cautious Neagu. Through his fatalism and wariness, the audience gets a sense of the pent-up frustration resulting from decades of service under Communism. Though a bit stiff on-screen, Paul Ipate has some finely turned moments as Andronescu as well. More than anything, though, Blue is about conveying the in-the-moment feeling of a particularly time and place, in all its madness.

Blue is an excellent representative of Romanian film for a number of reasons. It certainly dramatizes a critical moment in recent history, but it also proves that the films of the Romanian New Wave are not necessarily long, slow, or moody. Raw and visceral, Blue packs a punch. Its title also makes perfect sense in retrospect, but to explain why would be telling. Blue closed the 2011 Romanian Film Festival at the Walter Reade Theater this past Sunday (12/6), with a special post-screening Q&A with Muntean.