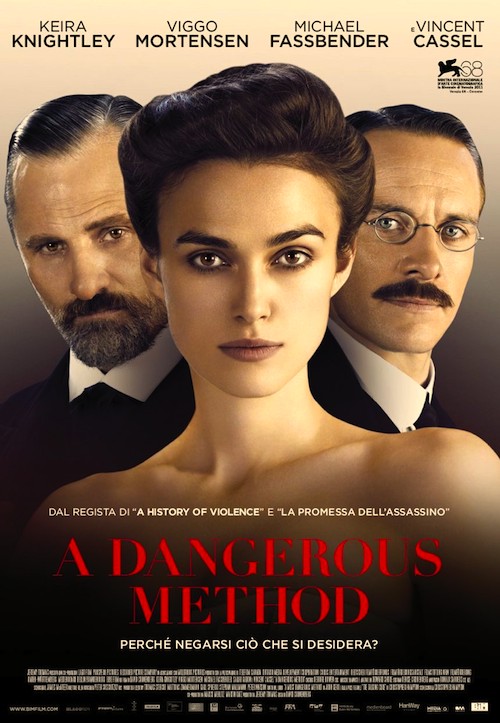

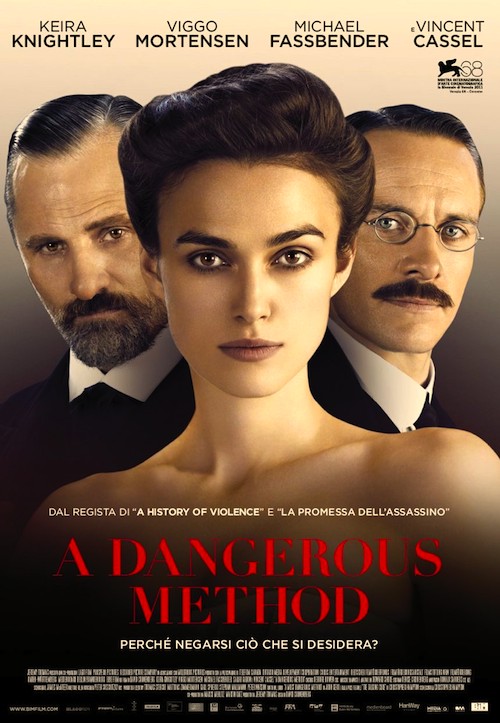

By Joe Bendel. Jungians consider Freud to be unnaturally sex-obsessed. Conversely, Freudians argue Jung debased the science with his superstitious mumbo-jumbo. Probably they are both more right than wrong. The birth of this great and enduring rivalry is dramatized in David Cronenberg’s A Dangerous Method (a trailer here), which screens tonight as a gala selection of the 49th New York Film Festival.

By Joe Bendel. Jungians consider Freud to be unnaturally sex-obsessed. Conversely, Freudians argue Jung debased the science with his superstitious mumbo-jumbo. Probably they are both more right than wrong. The birth of this great and enduring rivalry is dramatized in David Cronenberg’s A Dangerous Method (a trailer here), which screens tonight as a gala selection of the 49th New York Film Festival.

Carl Jung married well and lives an upright life. A leading practitioner in a controversial new field of study, he is eager to apply the methods of psychoanalysis advocated by Sigmund Freud. Sabina Spielrein represents the perfect opportunity. Though possessing a rather sharp intellect, she is so profoundly disturbed she cannot function in society. Yet, when Jung gets her talking, the roots of her mental torment become clear. While the word “cured” might be too strong a term, she is able to study medicine, with the intent of becoming of psychiatrist herself. Everything might have ended happily at this point, were it not for the libido’s self-destructive drive.

After giving into temptation once or a couple dozen times, the guilt wracked Jung breaks things off with his sort-of former patient rather precipitously. This drives the newly agitated Spielrein to seek the treatment of Jung’s new mentor, Dr. Sigmund Freud. As a result, Freud becomes somewhat disappointed in his younger colleague, while Spielrein increasingly aligns herself with the Freudian in her academic writings. Not surprisingly, this exacerbates the philosophical division between Freud and Jung.

Though clearly not nearly as renowned as her male colleagues, Spielrein arguably led the more cinematic life. A Russian Jew who tragically returned to her Soviet era homeland, much of Spielrein’s family perished during Stalin’s reign of terror, while she was eventually killed by the National Socialists. Not just a beautiful woman, her scholarship is thought to have possibly influenced both Jung and Freud. (Jung also spanks her quite a bit in Method, if that happens to be your thing.)

Kiera Knightley really goes for broke as Spielrein, laying on the accent a tad thick, but bringing a remarkable physicality to the role. She makes neurotic twitchiness rather hot. Despite having the screen time of a supporting player instead of a lead, Viggo Mortensen is convincingly smart and compulsively watchable as Freud, avoiding all the shticky goatee-stroking clichés associated with the iconic figure. Whereas the always tightly-wound Michael Fassbender is appropriately intense depicting Jung’s deeply rooted tension-and-release behavioral patterns.

Kiera Knightley really goes for broke as Spielrein, laying on the accent a tad thick, but bringing a remarkable physicality to the role. She makes neurotic twitchiness rather hot. Despite having the screen time of a supporting player instead of a lead, Viggo Mortensen is convincingly smart and compulsively watchable as Freud, avoiding all the shticky goatee-stroking clichés associated with the iconic figure. Whereas the always tightly-wound Michael Fassbender is appropriately intense depicting Jung’s deeply rooted tension-and-release behavioral patterns.

Adapted by Christopher Hampton from his stage play, which in turn was adapted from John Kerr’s book, Method’s greatest problem is its flattening narrative arc. Had it followed Spielrein through her demise in WWII it would have ended on a more significant, if tragic note. As it stands though, Method just appears to run out of story.

Throughout Method, Cronenberg adroitly handles both the rigorous intellectual debates and the provocative sexuality, largely rendering the latter with wise restraint. Probably more highbrow than old school Cronenberg fans might expect, he and Hampton clearly seem to want to present this critical period in the development of psychological study for its own sake rather than as a vehicle for lurid melodrama. It just lacks that epiphany moment. Frequently fascinating nonetheless, the overall solid Method screens twice tonight (10/5) at Alice Tully Hall as part of the 2011 New York Film Festival.

Posted on October 5th, 2011 at 12:o4pm.