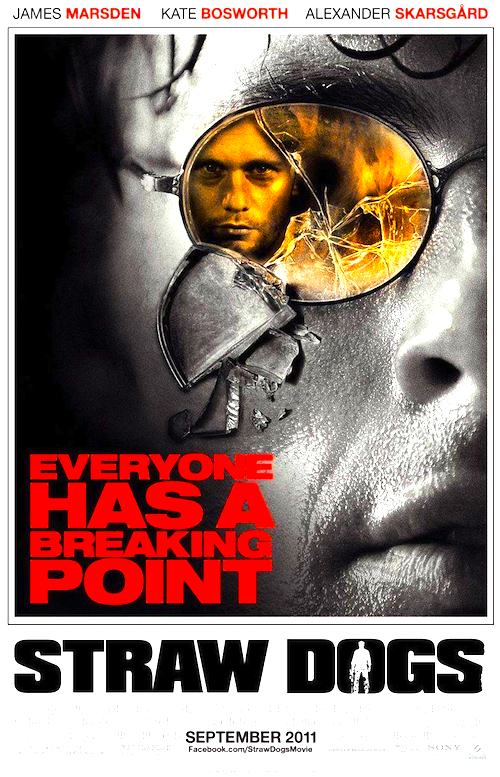

By Joe Bendel. “Dueling Banjos” must be expensive music to license. It’s about the only thing missing from the formerly indie Rod Lurie’s Red State-phobic remake of Sam Peckinpah’s career-defining film, Straw Dogs. Transferred from the English countryside to the Deep South, the once edgy examination of violent human nature is now a standard issue killer hillbilly movie, which opens today nationwide.

The prodigal television ingénue Amy Sumner tells her screenwriter husband David her hometown of Blackwater, Mississippi is properly pronounced “Backwater.” There you have the film’s flash of wit. It also tells viewers what to expect of the locals. Everyone watched her cancelled show, including her former high school beau Charlie Venner, whom her husband hires to fix their hurricane damaged barn. In retrospect, this is a bad idea.

Venner, his brother Darryl, his other brother Darryl, and their wacky next door neighbor, the unmistakably psychotic Norm, do not exactly hustle on the job, taking plenty of breaks to leer at her and deride his manhood, such as it is. Things quickly escalate when one of the good old boys strings up the family cat in their closet. Yet Sumner will not confront them directly, preferring to confuse them with his cryptic beating around the bush. Eventually though, things get way out of hand, forcing Sumner to defend home, hearth, and Jeremy Niles, a developmentally disabled grown man with an implied history of inappropriate behavior – whom the gruesome foursome and their former football coach, Tom Heddon, are out to lynch.

Venner, his brother Darryl, his other brother Darryl, and their wacky next door neighbor, the unmistakably psychotic Norm, do not exactly hustle on the job, taking plenty of breaks to leer at her and deride his manhood, such as it is. Things quickly escalate when one of the good old boys strings up the family cat in their closet. Yet Sumner will not confront them directly, preferring to confuse them with his cryptic beating around the bush. Eventually though, things get way out of hand, forcing Sumner to defend home, hearth, and Jeremy Niles, a developmentally disabled grown man with an implied history of inappropriate behavior – whom the gruesome foursome and their former football coach, Tom Heddon, are out to lynch.

Strangely, Lurie’s adaptation hardly ever deviates from the basic structure of Peckinpah’s original, yet he clearly has no clue what made the original so effective. For one thing, the 1971 film pulled a cultural reverse, unleashing a violent maelstrom against the picturesque backdrop of Cornwall, while casting a Yank as the pacifist victim. However, a city slicker terrorized by a pack of southern hicks is a real dog-bites-man story in Hollywood.

As a nebbish mathematician, the responses of Dustin Hoffman’s Sumner also made more sense in the context of Peckinpah’s film. It is not hard to imagine that he might have been bullied before, and was reverting to old survival strategies in his attempts to befriend his antagonists. In contrast, James Marsden’s snobby, Jag-driving, outspokenly atheistic screenwriter never seemed to have a bad day in his life before he got to Blackwater. Frankly, Venner might be a knuckle-dragging neanderthal, but he has a point when he tells Sumner it was rude to walk out during the pastor’s sermon. Of course, in real life he should not be brutalized for such boorishness, but in a sleazy exploitation film (which is really what the new Straw is) it is a close call. Continue reading Exploiting Peckinpah: LFM Reviews The Straw Dogs Remake