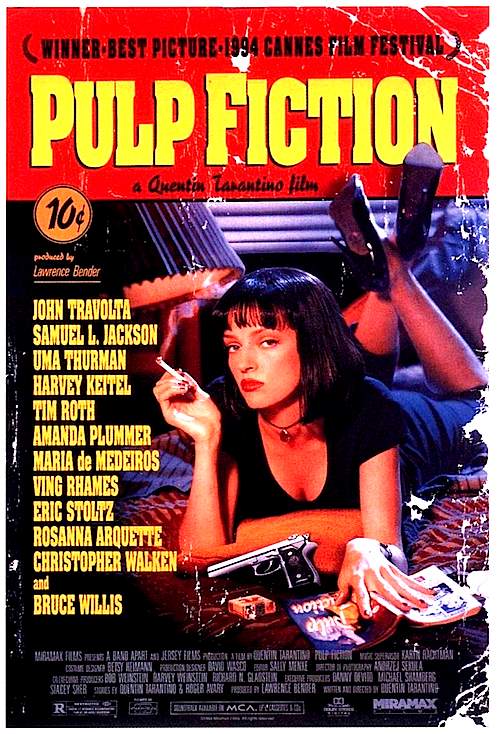

By David Ross. “Independent film” is defined by its circumvention of the Hollywood production mechanism, but this is incidental. The issue is not process but content. Independent film is an indigenous American genre just like the science-fiction film, the noir film, and the Western. Its chief attribute is loquacity. Talk is cheap – literally – and independent movies have made a virtue of necessity by rediscovering what Hollywood can afford to forget: that dialogue is the basis of drama. Less cardinal but still defining attributes include gritty naturalism (almost always urban), cultural and moral skepticism, a penchant for irony and deadpan, identification with pitiable outsiders and addled anti-heroes, impatience with traditional sequential narrative, appreciation for the retro, and a certain seated or merely ambulatory anti-kinesis (not a few films, like Slackers and Before Sunrise, narrate a literal walk). Independent film disdains the happy ending and could not care less about sex or sexiness or conventional good looks (hence Steve Buscemi). The operative politics tend to be amorphously anti-establishmentarian, but too skeptical to be actively liberal. I could make an excellent argument for the conservatism of films like Annie Hall (1997), Metropolitan (1990), Barcelona (1994), and A Serious Man (2009).

The films of the “Easy Rider, Raging Bull” era – films like John Schlesinger’s Midnight Cowboy (1969), Peter Bogdanovich’s Last Picture Show (1971), Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets (1973) and Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (1974), Roman Polanski’s Chinatown (1974), and Sydney Lumet’s Dog Day Afternoon – heralded the independent film movement, but were not strictly seminal. They yearned to be epic, mythic, and culturally central, with John Ford, Howard Hawks, and John Huston in mind. Independent cinema would later snort at these manly pretensions, settling for a peripheral and ironic self-awareness, like the satirical wallflower at the high school dance.

The films of the “Easy Rider, Raging Bull” era – films like John Schlesinger’s Midnight Cowboy (1969), Peter Bogdanovich’s Last Picture Show (1971), Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets (1973) and Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (1974), Roman Polanski’s Chinatown (1974), and Sydney Lumet’s Dog Day Afternoon – heralded the independent film movement, but were not strictly seminal. They yearned to be epic, mythic, and culturally central, with John Ford, Howard Hawks, and John Huston in mind. Independent cinema would later snort at these manly pretensions, settling for a peripheral and ironic self-awareness, like the satirical wallflower at the high school dance.

The first true – and possibly best – independent film was Annie Hall. Inspired by European conversationalists like Ingmar Bergman and Eric Rohmer, Woody Allen created an aggressively small and verbal film in an era of equally aggressive hypertrophy and hyperactivity. Perhaps even more to the point, Annie Hall was a quietly scathing critique of the post-sixties liberal and pop-cultural order, setting the tone for a whole generation of filmmakers united by the instinct that “something is wrong,” though skeptical of their own capacity for overt social statement in the style of seventies masterpieces like A Clockwork Orange (1971) and Network (1976). Gabby symposia like Louis Malle’s My Dinner with Andre (1981) and Barry Levinson’s Diner (1982) further crystallized the verbal and essentially seated nature of the genre. Continue reading An Independent Film Hall of Fame