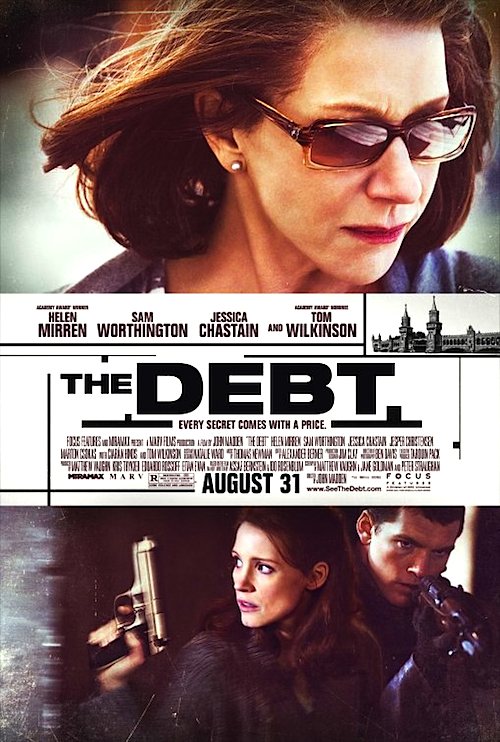

By Joe Bendel. Rachel Singer understands the dark side of human nature. After all, her ex-husband Stephan Gold is a high-ranking cabinet official, and her daughter Sarah Gold is a journalist. In fact, Gold’s new book has reopened a number of old wounds for her parents. Singer and Gold were part of a three agent Mossad team charged with capturing “The Surgeon of Birkenau,” a National Socialist war criminal clearly modeled on Mengele. Though they were supposedly forced to kill the doctor when he attempted to escape, we quickly discover there is something wrong with the official story in John Madden’s restructured The Debt (trailer here), which opens today in New York.

By Joe Bendel. Rachel Singer understands the dark side of human nature. After all, her ex-husband Stephan Gold is a high-ranking cabinet official, and her daughter Sarah Gold is a journalist. In fact, Gold’s new book has reopened a number of old wounds for her parents. Singer and Gold were part of a three agent Mossad team charged with capturing “The Surgeon of Birkenau,” a National Socialist war criminal clearly modeled on Mengele. Though they were supposedly forced to kill the doctor when he attempted to escape, we quickly discover there is something wrong with the official story in John Madden’s restructured The Debt (trailer here), which opens today in New York.

Based on Assaf Bernstein’s Israeli film of the same title, The Debt first presents the account of the fateful mission that made Singer a national icon in Israel. It is that story Sarah Gold told in her bestselling book, which Singer dutifully agrees to help publicize. Yet, when press reports surface of a senile patient in a Ukrainian nursing home claiming to be the notorious Surgeon, Dieter Vogel, she and her ex take it deadly seriously. So does David Peretz, the third member of the team, who was always too troubled by the events that transpired in 1965 East Berlin to enjoy their heroic celebrity.

Now a wheelchair-bound senior intelligence official, Gold’s field ops days are behind him. Though the conscience plagued Peretz has recently reappeared, he will be in no condition to deal with the Surgeon. It is up to Singer to covertly enter Ukraine and finish the job. While she cases the sanatorium, The Debt flashes back to East Berlin, showing how it all really went down.

As adapted by screenwriters Matthew Vaughn & Jane Goldman and Peter Straughan, Madden’s Debt closely hews to the plot and structure of the original. However, the new version plays up the three Mossad agents’ romantic triangle and also adds a bit of a moralizing “truth is important” spin to the ending. However, like the source film, The Debt never suggests Singer’s team had the wrong man, only faulting their execution, the result of stress exacerbated by generational guilt and sexual tension. Indeed, The Surgeon is presented as evil incarnate, played with icy menace by Jesper Christensen.

When casting an actress of a certain age for a somewhat action oriented film, Helen Mirren is pretty much the extent of the short list. Though she brings the appropriate presence and credibility to the 1997 Singer, the heart and guts of the film remain in 1965 (as was the case with its predecessor). Madden cranks up the claustrophobic tension in their “safe” flat quite effectively, while making it vividly clear how the legacy of the Holocaust weighed on the team as first generation children of survivors.

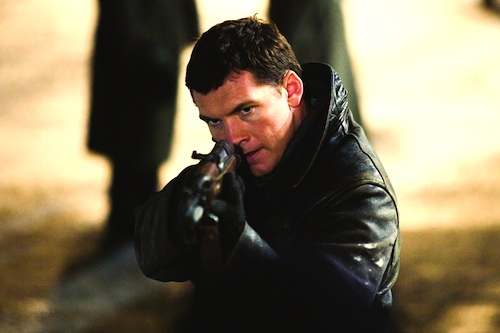

Frankly, Sam Worthington is surprisingly compelling as the young but already too tightly wound Peretz, suggesting he might actually be a very good actor, who just had the mixed luck to be in utterly terrible but hugely successful films like Avatar and Clash of the Titans. Yet, perhaps the greatest surprise is Jessica Chastain, who rises to challenge of playing the same character as Dame Helen in the same film. In fact, she might even get the better of her, investing the younger Gold with equal measures of strength and vulnerability.

Though it still has not fixed the problematic third act showdown, The Debt remains a leanly muscular morality play-thriller. While the English language version might be a bit more inclined to cast the Mossad in an unfavorable light, there is never any ambiguity as to the Surgeon’s truly malevolent nature. A surprisingly faithful and well executed remake, The Debt should definitely satisfy those who enjoy a John Le Carrré-esque story, who have do not already know the twists and turns of the original. It opens today (8/31) in New York at the Angelika Film Center.

Posted on August 31st, 2011 at 6:14pm.