By David Ross. Over two years, my nearly-six-year-old daughter and I have blown through all of Narnia, all of Harry Potter, and nearly all of Phillip Pullman’s great Dark Materials trilogy. She was attentive to Narnia and delighted by Harry Potter, but Pullman has entranced her to the extent that her face goes long with shock and anguish when I close the book and tell her to shout down the stairs for her nightly cocoa. Our next adventure is The Hobbit and its sequels. After tramping the roads with Frodo for six months, she will be primed for The Odyssey, beyond which lies the great Western sea of literature in all its dimensions of imagination and idea.

This program depends on the strict suppression of competing media (broadcast television, computer games, and web-surfing are verboten) and the realization that kids are by nature imaginative and that all attempts to subordinate the imagination to didactic and activist aims will produce a backlash of reluctance and indifference. Heather has two mommies, you say? This is a curious detail, worth a question or two, but not conducive to make-believe games or ruminations in the dark of bedtime. How much better if one of Heather’s mommies were a reincarnated Egyptian princess or a fairy queen cruelly trapped in a mortal body. This is not a political or literary judgment, merely an observation about developmental psychology.

Barbara Feinberg’s useful memoir of her kids’ reading, Welcome to Lizard Motel: Children, Stories, and the Mystery of Making Things Up, elaborates much the same point. Her basic thesis is that kids resist reading because contemporary books are insufferably pedantic and boring. This assumes that kids still read books at all. These days, schools seem happy enough to replace books with assorted ‘educational materials,’ not realizing or caring that these have all the romantic resonance of the suburban office parks where they were developed.

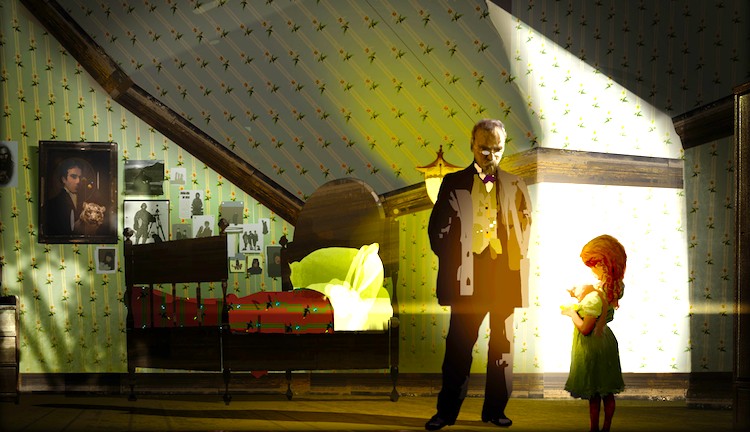

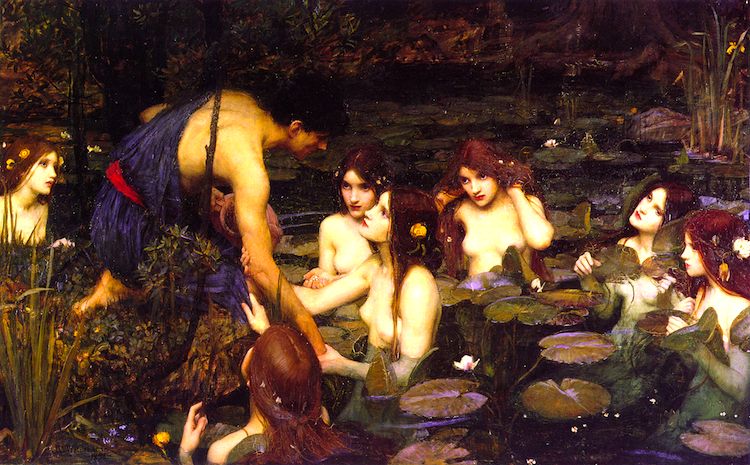

With the right bait, the fish is easily hooked. Not long ago my daughter happened to look over my shoulder as I perused a book of paintings by J.W. Waterhouse, the pre-Raphaelite master. She drank in the scowling witch (Circe) and the dead lady in the snow (St. Eulalia) and the beautiful lady in the boat (the Lady of Shalott) and the young man saying hello to the beautiful water fairies (Hylas and the Nymphs). These are images to trigger reactions in recesses of the brain not usually exercised in school, in comparison to which the images of her everyday visual field – all those bright socially aware posters in the hallways, for example – are pablum. She added the Waterhouse book to her “birthday list,” which in our house is the ultimate form of canonization. Continue reading Kids, Imagination & The Arts