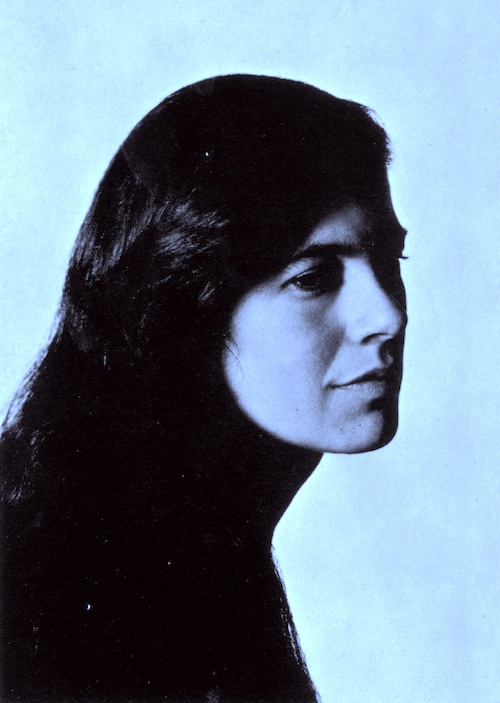

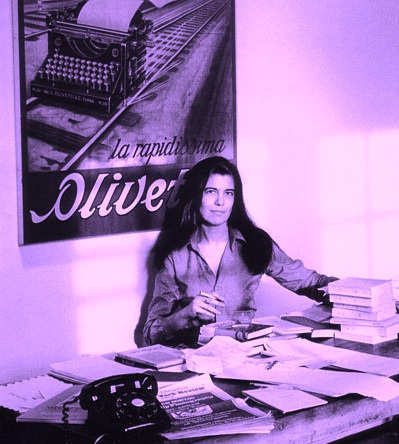

By David Ross. Sigrid Nunez was during the mid-1970s Susan Sontag’s secretary and her son David Rieff’s lover. Her recently published memoir Sempre Susan (read a racy excerpt here) has improbably returned Sontag to the spotlight, just when her long slow fade seemed to have begun in earnest. A mandarin even by the standards of the intelligentsia, Sontag did much to instate the European art film as a phenomenon of the intellectual vanguard during the 1960s and 1970s.

So too her look and bearing codified what it meant – and still means – to be a ‘serious intellectual.’ Sontag always struck me as feline: elegant, self-contained, sharp-clawed, well-groomed (intellectually and physically). To extend my metaphor, I imagine her as a silky Persian cat perched atop a garden wall, occasionally glancing with disdain at all the mere dogs clumsily being dogs below – romping idiotically, smelling each other’s behinds, crapping in the bushes, having fun.

This semester I gave my students Sontag’s essay on Godard’s Vivra Sa Vie, one of several self-consciously ‘important’ essays on film anthologized in Sontag’s breakthrough volume Against Interpretation (1966). I admire its elegant minimalism (rather like the movie itself), but I find it lacking in heft and emotional engagement (again like the movie itself). I paired Sontag’s essay with our own Jennifer Baldwin’s photo-essay on Vivra Sa Vie, which in many ways I consider more satisfying because more immediate and more human. My students laughed at Jennifer’s cri de femme: “I want Nana’s fuzzy black coat.” Sontag did not make the students laugh. I wonder if she ever made anybody laugh. Possibly not.

Virginia Woolf said of Yeats, “Wherever one cut him, with a little question, he poured, spurted fountains of ideas.” This Titanism – this quality of thinking and being on a grand scale, of bringing to bear the whole of one’s self – is the hallmark of the great intellectuals. Sontag never pours or spurts. She makes a clinical exercise of what should be a vast excitement.

In terms of film criticism, I favor Pauline Kael, if only because she understood the cardinal romantic truth that intellect is merely an expressive device of the personality. Kael suffers from serious lapses in taste and judgment, but her wild and woolly prose is more alive than Sontag’s and her passions more transparent and seemingly sincere. Sontag was more sophisticated in her range of interests and enthusiasms, but only more serious and ambitious in a way. She was interested in exploring her own capacity for exploration, interested in her own mind and what it could figure out. Her form of criticism is a kind of intellectual ceremony, a kind of Japanese tea ceremony in which Sontag dispenses herself in refined and smallish doses. In the end, Sontag is a bit too astringent for my taste. A film should not be an intellectual puzzle or a pretext for critical experiment; it should be a hub of personal meaning.

I reread yesterday Sontag’s “Notes on Camp,” also from Against Interpretation. It’s a brilliant little piece, but it says far more about Sontag herself than about camp. Its real content is the curious involutions of its own form and expression. It is about itself, and in this regard functions more like a poem – a clever but dry one – than like criticism properly defined. Continue reading Sempre Susan