By Joe Bendel. Nearly any art the Soviets would suppress, Igor Savitsky collected—using their money. In a remote corner of Central Asia, Savitsky built the Nukus Museum to house an extraordinary collection of Soviet modernist and Uzbekistani folk art. This unlikely institution and its visionary founder are introduced to the world at-large in Amanda Pope and Tchavdar Georgiev’s fascinating documentary, The Desert of Forbidden Art, which opens today in New York and next week in Los Angeles. Continue reading Suppressed Soviet Art: LFM Reviews The Desert of Forbidden Art, Narrated by Ben Kingsley

Month: March 2011

LFM Review: Time of Eve @ The New York International Children’s Film Festival

By Joe Bendel. As usual, Isaac Asimov got it right. In the future, robots follow his three laws. However, there are still a lot of grey areas for androids, including the very nature of their existence. Two high school students grapple with the notion of human-android relations in Yasuhiro Yoshiura’s Time of Eve, a surprisingly smart science fiction anime feature adapted from his webseries, which screens during the 2011 New York International Children’s Film Festival. Continue reading LFM Review: Time of Eve @ The New York International Children’s Film Festival

What a Revolution Should Look Like: The Power of the Powerless

By Joe Bendel. Initially, the student-driven revolution against Czechoslovakia’s hardline Communist government seemed hopelessly naïve. In a mere eleven days, the humbled regime relinquished their dubious claim to power, clearing the way for democratic elections. Unlike the current Middle Eastern “Days of Rage,” it all transpired without demonstrators committing any sexually, ethnically, or religiously motivated acts of violence. In fact, whether Havel and the Velvet Revolution were too forgiving of their former oppressors is one of the questions raised in Cory Taylor’s documentary, The Power of the Powerless, which opens this Friday in the Los Angeles area. Continue reading What a Revolution Should Look Like: The Power of the Powerless

Celebrities Who Perform for The Qaddafis

By David Ross. Celebrity avarice doesn’t get any lower than this. Rolling Stone reports (here and here) that numerous stars have received massive paychecks to perform for the family of Muammar el-Qaddafi.

Over the past few years, Muatassim Qaddafi [the colonel’s playboy son] has spent hundreds of thousands of dollars hiring prominent western performers to provide music for his private events. In 2008, Mariah Carey accepted a $1 million fee, according to WikiLeaks cables and news reports, to sing four songs for a New Year’s Eve party. 50 Cent has performed at Qaddafi functions in the past. Beyoncé was the main attraction at the New Year’s Even party, which took place on at Nikki Beach, on the Caribbean island of St. Bart’s party. Usher, according to reports, also performed there, and Lindsay Lohan, Jay-Z, Jon Bon Jovi and other celebrities were in the audience.

Nelly Furtado, meanwhile, received $1 million to perform a forty-five-minute show in Milan in 2007. What next? Justin Bieber coming soon to an Afghan cave near you!

It’s hard to know which is more deplorable: celebrity greed or Qaddafi taste. In the attempt to shake the desert sand from their robes, rogue dictators seem to have looked no farther than US magazine and Cribs. I suppose it’s helpful intel that our geopolitical adversaries are holed up in their bunkers with the complete Laguna Beach on DVD. Maybe Selena Gomez can pitch in and do some role playing with Hilary Clinton – you know, to give her a feel for what Middle Eastern tyrants are into.

Rolling Stone, now a wholly owned subsidiary of Shepard Fairey Inc., cannot resist a final ludicrous insinuation of moral equivalency:

Artists have long taken money to play private shows for clients whose political agendas might be offensive to their fans, from B.B. King jamming with the late Republican strategist Lee Atwater in the Eighties to Elton John singing at Rush Limbaugh’s wedding last year.

This dig appears in the print edition of the story, but not on-line. Good call. The blogosphere would have fed like piranhas on this.

Posted on March 9th, 2011 at 10:35am.

Inception as Epic of Narcissism

By David Ross. I saw only a few Hollywood films this year. Among Oscar contenders, I caught The Social Network (a well-told tale within narrow parameters), Toy Story 3 (a film our great-grandkids will revere no less than we do), How to Train Your Dragon (Avatar without the brainless politics), and Inception (ludicrous spew of egomaniacal director).

What to say about Inception, a film so self-enamored that it twists itself into knots the better to quaff the fragrance of its own rear end? It’s just bad. Badly acted, badly directed, badly written.

Science fiction is supposed to trace the arc of human possibility and send us postcards from our own future, or at least from a conceivable future. Inception, like the Wachowski brothers’ Matrix and Steven Spielberg’s Minority Report, imagines a factitious technological development and spins a strictly arbitrary tale. There’s no reason to give a damn. Inception is not about the implications of our present reality but about itself. It’s fixated on the superficial dazzle of its own self-enwound idea. Dr. Apuzzo’s review in these pages appeared upside down (see here), but it might equally have appeared in mirrored reverse, to indicate the film’s narcissus gaze.

And then there is Leonardo DiCaprio, the baby-faced siren who lures directors to their artistic deaths. DiCaprio’s fatal attraction is one of the great mysteries. Do directors remember Titanic and see nine zeros where a performance is supposed to be? He’s lumbering, puffy, and nerveless, genetically closer to Keanu Reeves than to Al Pacino or Robert DeNiro. Christopher Nolan is taken in – okay, we expect as much; but Martin Scorsese four times? DiCaprio has laid waste a whole generation of potentially good films, starting with Danny Boyle’s The Beach. Brad Pitt has also ruined his share of films, but he has not gotten his mitts on nearly as many prestige projects.

Ellen Page is cute enough, and I enjoyed Juno as much as the next nerd who likes to see his own kind hold its own on screen, but no actress is less destined to be the next Sigourney Weaver. She jumps, she runs, she shoots, all the while conveying the sense that she’d much rather be reading Zadie Smith in some nice coffeehouse of the mind or maybe working on her grad school applications.

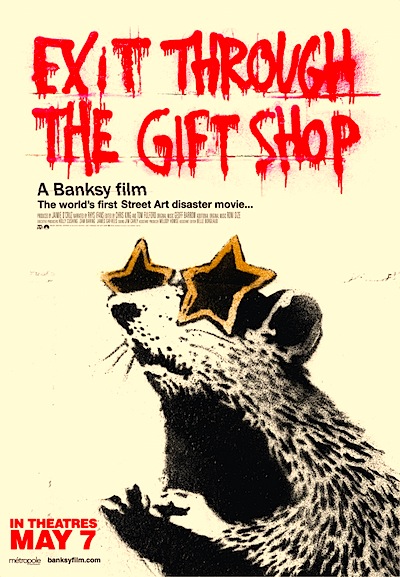

I did see one more Oscar nominee, come to think of it. Exit through the Gift Shop is a strange piece of work: a documentary about an aborted documentary about street art. It follows the director of the aborted documentary, Thierry Guetta, as he evolves from vintage clothing store owner, to illicit street-art videographer, to daredevil street artist called Mr. Brainwash, to celebrity artist in his own right, despite having no training or experience whatsoever. Guetta now sells his Warhol-style lithographs for large sums at the highest strata of the auction world. Complicating matters, there’s speculation – probably correct, if I had to guess – that Exit through the Gift Shop is an elaborate prank perpetrated by its director, the legendary street artist Banksy, and that Guetta is merely a Banksy frontman. The Times of London floats this theory here.

Whether documentary or mockumentary, Exit through the Gift Shop is, at the very least, a postmodern artifact to be reckoned with. It begins by celebrating the authenticity of street-art heroes like Shepard Fairey (creator of the red, white, and blue Obama icon) and Banksy himself; it morphs into a deconstruction of postmodern inauthenticity as the putatively talentless Guetta manufactures a vast body of work in no time and successfully sells himself as the latest phenom to emerge from the streets; it morphs again into a vindication of Banksy on the assumption that Guetta has become rich and famous selling art that is, after all, Banksy’s.

What to make of this? Exit‘s pretzel-logic is no less involved than Inception‘s, but we find ourselves implicated in it; its maze is our maze, and we have a vested interested in finding our way out. Something, for once, is at stake.

Posted on March 8th, 2011 at 10:04am.

Jafar Panahi (Not) at The Asia Society: The Circle

By Joe Bendel. It is good to be a man in Iran, provided you do not care about religious, political, or economic liberty. However, women must endure a profoundly misogynistic and frequently brutal society that regards them as little more than the chattel of men. Jafar Panahi confronted the unjustness of Iran’s treatment of women directly in The Circle, the winner of the 2000 Venice Film Festival’s Golden Lion prize – and a film which was promptly banned in Iran. Not content to stop there, the Iranian government has recently barred Panahi from further filmmaking for the next twenty years and sentenced him to six years in prison. Indeed, Panahi’s circumstances only heighten the poignancy of The Circle, which screens this Friday as the concluding film of the Asia Society’s retrospective-tribute to the persecuted filmmaker.

Solmaz Gholami (remember that name) has just given birth to a healthy baby girl. This should be happy news, but her mother is distraught. The in-laws were expecting a boy and will surely abandon their daughter-in-law and grand-daughter. The obvious high school science fact that it was the husband who failed to supply the Y chromosome is lost on such medieval fundamentalists. As Gholami’s mother seeks help from her family, Circle peels off, focusing on its next set of characters.

Three women have just been released from prison on unspecified “morals” charges. However, the Iranian system sets them up in a perverse Catch-22, kicking them loose without the necessary identification papers should they be stopped once again by the police (who are definitely out hunting for women in their situation). Lacking a male chaperone, sweet-tempered Nargess cannot take the bus trip back to her provincial home. Despondent, she seeks another friend, Pari, an escapee with even greater problems. She is four months pregnant with the child of her executed lover. From Pari, the chain continues, introducing a desperate mother and a woman arrested as a prostitute (perhaps not without some justification in her case), who ultimately brings the story to its symmetrical conclusion.

Sexism is a wholly insufficient term for the abuses Circle dramatizes. A stinging indictment – but also an honest, frequently moving human drama – it is not hard to see how it ran afoul of the state censors. Yet the film is not just a testament to Panahi’s artistic integrity. The cast deserves tremendous credit, especially those playing fallen women while living under a literal-minded fundamentalist theocracy. Though Circle is the only credit listed on IMDB for many of the actresses, their work has a powerful immediacy. They are frighteningly believable. Perhaps most haunting is Nargess Mamizadeh as her namesake. Young and innocent, to paraphrase the tagline of one of Circle’s international posters, she could only be guilty of being a woman.

To be banned by the mullahs might be a greater accolade than the raft of awards Circle won on the international festival circuit. Of course, the repercussions for Panahi have been severe. A truly bold film, Circle has only appreciated in importance and relevance with the regime’s campaign against the filmmaker. Highly recommended, it screens this Friday (3/11) at the Asia Society—and once again, tickets are free.

Posted on March 7th, 2011 at 10:01am.