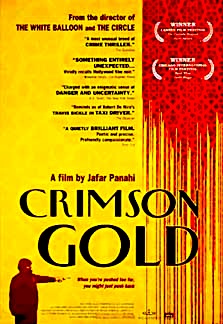

By Joe Bendel. The Iranian government’s record on human rights is certainly lacking, but anything less than a completely equitable distribution of the country’s vast oil revenues must represent the highest form of hypocrisy. Indeed, the Islamic Republic stands so charged in Jafar Panahi’s Crimson Gold, the winner of the Un Certain Regard Jury Prize at the 2003 Cannes Film Festival. Unfortunately, social criticism is a dangerous proposition in Iran. It earned Panahi a six year prison sentence and a twenty-year filmmaking ban. Needless to say, Panahi will not be in attendance when Crimson screens this Friday as part of the Asia Society’s retrospective-tribute to the persecuted filmmaker, but its depiction of a contemporary Iran illiberal in nearly every way speaks volumes.

There is something profoundly unsettling about Hussein. Though he walks through life in a haze, a little like James Franco at the Oscars, there is a great deal of anger and resentment roiling below the surface. We know right from the start, it is not going to work out for him. Through the circular narrative of celebrated Iranian director Abbas Kiarostami’s screenplay, the audience witnesses the events that drove Hussein to his tragic hold-up attempt.

There is something profoundly unsettling about Hussein. Though he walks through life in a haze, a little like James Franco at the Oscars, there is a great deal of anger and resentment roiling below the surface. We know right from the start, it is not going to work out for him. Through the circular narrative of celebrated Iranian director Abbas Kiarostami’s screenplay, the audience witnesses the events that drove Hussein to his tragic hold-up attempt.

Hussein and Ali, the brother of his fiancé, work as pizza deliverymen and dabble in a bit of purse-snatching. One otherwise unremarkable purse holds a receipt for an extravagantly expensive necklace. Intrigued, they proceed to the high-end jewelry store out of curiosity, only to be turned away as the low class riffraff they so obviously are. Hussein’s resulting umbrage will be his undoing, eventually leading us back to where the film started, but the getting there will be both oppressively naturalistic and at times surreal.

Hussein is one of the Islamic Republic’s disposable people, a psychologically traumatized Iran-Iraq War veteran living in abject squalor. However, the mobility of his job allows him to observe both the glaring disparity between the have’s and the have-not’s, as well as the morals police at work. Crimson truly captures the absurdity of contemporary Iran when Hussein tries to deliver his pies to a scandalous party featuring verboten dancing between the sexes, only to be waylaid by the cops waiting outside to arrest each sinner as they leave. One of Crimson’s inconvenient ironies is the rigid fundamentalism of Hussein himself and his desperately poor neighbors.

Reportedly, Hussein Emadeddin was a nonprofessional actor living with paranoid schizophrenia when Panahi cast him as Crimson’s protagonist. Unlike the typical Hollywood-indie portrayal of mental illness, Emadeddin is never showy in the role. All his energy seems to be directed inward rather than outward. Beyond convincing, he is frankly eerie to watch lumbering through the margins of Iranian society—a ticking time-bomb waiting to explode.

In America, it is a compliment to call Crimson a challenging film. In the mullahs’ Iran, it constitutes a prison sentence. A pointed attack on hypocrisy and a somewhat more circumspect critique of Iranian social controls, Crimson is also compelling tragedy, deftly executed by Panahi. Worth seeing as a film in its own right, Crimson is only too timely given the circumstances of its director. Highly recommended, it screens this Friday (3/4) at the Asia Society and once again, tickets are free. In addition, the Society will host a panel discussion on Panahi and free expression in Iran (or the lack thereof) that will also be simultaneously webcasted here at AsiaSociety.org/Live.

Posted on March 2nd, 2011 at 11:22am.