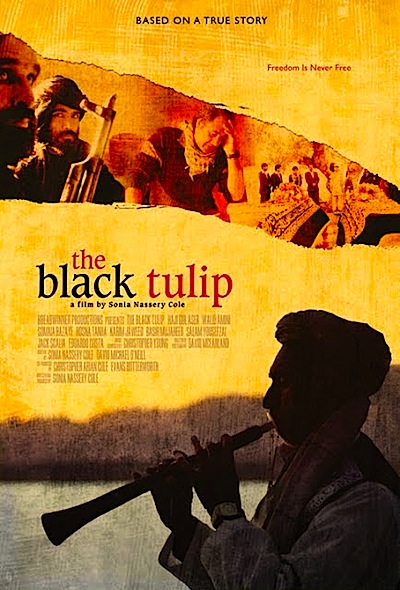

By Joe Bendel. The Taliban are not what you might call big movie buffs. Of course, anything involving free expression is pretty much a non-starter for them. After shutting down Pakistan’s cottage Pashto film industry, for example, they did their best to harass the cast and crew of Sonia Nassery Cole’s The Black Tulip. Yet she persevered, eventually completing the only film produced in Afghanistan this year.

Though duly submitted as the country’s official submission for best foreign language Oscar consideration, the Academy unfortunately disqualified Tulip on grounds that seem highly debatable.

Since Cole and company are presumably working to secure festival slots and theatrical distribution, a review as such would be premature. However, having seen it two weeks ago at a New York Times event, one hopes more people will have a chance to share the experience. As writer, director, producer, and lead actress, Cole was nearly a one man band. Still, she and cinematographer Dave McFarland produced a slickly professional looking film that bears no resemblance to zero-budget Pashto films featured in George Gittoes’ jaw-dropping documentary The Miscreants of Taliwood (trailer below).

In fact, Cole displays a real talent for pacing and shot composition. Conversely, her acting is not exactly at the same level. To be fair, she was reportedly a last minute substitution when the Taliban hacked off the feet of the woman she had originally cast as the protagonist, Farishta. Naturally, the same New York Times has devoted a fair amount of article space to those who dispute this account – largely it seems, because they prefer not to deal with its implications. Had Cole had an actress like the great (and great really is the word) Shohreh Aghdashloo in the lead, the mind reels at what could have been. Perhaps the film’s greatest revelation though, is the consistent quality of the Afghan cast, particularly Haji Ghul Aser as her husband Hadar.

There are many reasons why Tulip is an important film. Indeed, it is truly fearless in its portrayal of the Taliban’s savagery. Even more controversially, it also depicts the American military as a positive presence in Afghanistan, forging links of friendship with average citizens. Yet, the most valuable aspect of Tulip is the window it opens into an Afghan middle class most Americans probably assume does not exist. Tulip shows audiences that not all Afghans are toothless mujahedeen with a Koran in one hand and a Kalashnikov in the other. Rather, there are many people like Farishta and Hadar, who simply want to work hard and raise their family.

Considering the state of filmmaking in the region, one would think the Academy would try to support films like Tulip as best they can. However, they disqualified Tulip from the best foreign language film category – apparently because Cole, an Afghan expatriate working with a largely American crew, were not deemed authentically Afghan enough.

Yet similar issues could be raised regarding the Algerian Oscar submission, Rachid Bouchareb’s Outside the Law. Bouchareb was born in France to a family of Algerian immigrants. And aside from the opening scenes, the film is also set entirely in France – featuring French movie stars, like Roschdy Zem and Jean-Pierre Lorit. Somehow though, this was apparently forgivable to the Academy given that the film is a critique of French colonialism.

Law is an excellent picture that deserves to be in Oscar contention, but if it meets the foreign language division’s criteria, it is hard to understand why Tulip would not. Maybe Cole’s film can still qualify for consideration in the best song category. Natalie Cole (no relation) recorded three originals for the soundtrack, including one legitimately stirring anthem with a popular Farsi vocalist.

Contact your local film festivals and societies about Tulip, because a film like this will need a groundswell of support.

Posted on December 15th, 2010 at 11:40am.