By Jason Apuzzo. When you’re the biggest female movie star in the world, and your personal man-servant is Brad Pitt, you can order up a film like The Tourist – more or less as you would order up room service at The Ritz.

That’s the ‘truth,’ such as it is, behind the new Angelina Jolie star vehicle that opens today, co-starring – technically, at least – Johnny Depp, and directed (so the advertising claims) by Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck.

Because if the phrase ‘vanity project’ has any meaning, then it applies with full force in describing The Tourist.

That’s not necessarily such a bad thing, in so far as Ms. Jolie is a genuine star – albeit, occasionally a star in the same way that Medusa was a ‘star’ of Greek mythology, earning her points by way of force rather than charm. But in the strange world we live in, in which people like Sandra Bullock or Reese Witherspoon are routinely and incorrectly referred to as ‘stars’ (rather than as what they are, which is ‘actresses’) Angelina Jolie is the genuine article, and The Tourist only confirms that. If there ever was a woman the camera loves as she walks into a crowded ballroom, or as she skeptically raises an eyebrow at a would-be suitor, or as she fixes an appraising gaze on a man she intends to possess – and destroy? – then it’s Angelina Jolie.

The problem is, star vehicles don’t always make for good films – and at a certain point, they also corrode the star’s image. (Ask John Travolta about that.) The Tourist is almost – if not quite – a disaster, a woeful and expensive attempt to mimic charming romantic espionage capers of the past like North by Northwest, Charade or Arabesque; and in the generally misogynistic calculus of today’s Hollywood, Jolie likely can’t afford many more films like it.

There’s more to The Tourist than that, though. There’s also a kind of snarky, dismissive tone taken by the film toward America and Americans that left me with a bad taste in my mouth. More on that below. The bottom line is that whereas I was ready to pass this film off as a harmless failure, an expensive lark – now I’m actively rooting for it to fail.

Frankly, I hope The Tourist tanks.

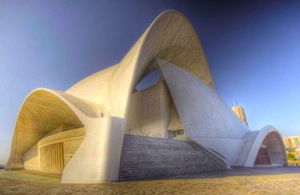

I’ll go through the motions and describe the film’s ‘plot,’ although ‘plot’ in this film is strictly an afterthought. We start with Jolie, who’s in Paris being surveilled by Scotland Yard for reasons as yet unknown. The Scotland Yard team is led by Paul Bettany and Timothy Dalton (highly underrated as James Bond, I might add) – just two members of this film’s expensive supporting cast, which also includes Steven Berkoff and Rufus Sewell. Jolie gives Scotland Yard the slip, and finds herself on a train bound for Venice where she picks up Depp as a decoy to keep her pursuers guessing. Complicating matters is that a crime lord (Berkoff) who’s also pursuing Jolie mistakes Depp for a criminal who recently made off with about a billion dollars’ worth of his dirty money. Double-crosses, pseudo-adventure, predictable revelations and passing glances at romance ensue.

A few other things ensue, as well. One of the film’s motifs is that of Depp acting out as a bumbling, graceless and naive American in one of Europe’s most exotic and resplendent cities: Venice. (It’s simultaneously one of Europe’s grimiest and crassly commercialized cities; even Goethe was complaining about it back in the 1790s, long before there were Americans around to ruffle anybody’s feathers.) Depp plays the 2010 version of the ‘ugly American’ overseas, although in this case he’s more like the bumbling, gauche American – and The Tourist tries to play his ‘fish-out-of-water’ status for as many cheap laughs as possible.

It’s pathetic, and none of it works. It also happens to be obnoxious – a ‘look at the dancing American monkey’ routine – and immediately reawakened my dormant contempt for all-things-Depp.

By why restrict my venom to Depp? How about the director, Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck? You can stick a fork in him. His 2007 film The Lives of Others was a breath of fresh air on a challenging, politically incorrect subject (i.e., the legacy of communism in Europe). Whatever good-will he established with that film has now been swiftly squandered – and for what? To play personal valet to big-dollar American movie stars on a European holiday? To indulge in cheap anti-Americanism, so he can fit in better with the Malibu gentry?

Donnersmarck does not appear to have ‘directed’ his stars here at all, actually. Perhaps he was over-awed by the talent suddenly put at his disposal. Jolie swans through the film doing her usual routine – which is fine, it’s a good routine, except that she lacks the vulnerability here that she shows in her better roles. As for Depp, he really needed to be directed because – conventional wisdom to the contrary – he is neither Cary Grant nor Laurence Olivier, and needed to bring more discipline to his performance (beginning with cutting his hair, and getting a shave) in order to be convincing as a math teacher from Wisconsin.

The deeper problem here, though, is that Hollywood is long out of practice making films like this – and it shows. The Tourist feels like a tourist ride through other, better films – films with higher stakes (as during the ideological struggle of the Cold War; one thinks here of Alfred Hitchcock’s Torn Curtain with Paul Newman and Julie Andrews), or with more style (say, Mario Bava’s Danger: Diabolik). Donnersmarck doesn’t want to take too many chances here, though, and potentially risk his shiny new Hollywood career; ironically, his career may now get scuttled by this film.

The temptation to ‘go Hollywood’ is a strong one, one that only the most willful and stubborn can withstand. It’s probably very tempting even for an Oscar-winner like Donnersmarck, with serious things on his mind, to become – in effect – little more than another member of Angelina Jolie’s livery.

There are no doubt worse fates, but some of us were hoping for more from him.

Posted on December 10th, 2010 at 6:14pm.