We love this. Part II will run tomorrow. Enjoy …

Posted on October 6th, 2010 at 9:07am.

We love this. Part II will run tomorrow. Enjoy …

Posted on October 6th, 2010 at 9:07am.

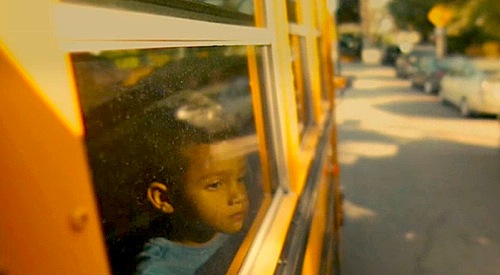

By Patricia Ducey. Waiting for Superman is an emotionally gripping and ultimately devastating critique of the American public school system, in the same vein as The Lottery or The Cartel and a host of previous education movies. Superman focuses on a half dozen children and their families – and their desperate quest to gain admittance to their city’s charter school. There are only a few spots in each school and many applicants; the filmmakers draw us in and–let’s be honest–manipulate us with the suspense leading up to what is characterized as a make-it-or-break-it day when the charter school chooses its next class by lottery. Will these children escape their neighborhood “dropout factory” and secure their futures?

Co-written with Billy Kimball, directed by Davis Guggenheim (An Inconvenient Truth) and produced by Jeff Skoll’s Participant Productions, this documentary possesses an authentic progressive pedigree. Skoll views films as vehicles for social change, a kind of “loss leader” that delivers butts in the seat to the alliances and activists he has already mobilized to capitalize on them (see here) and he hopes to do the same with Superman. Skoll greenlights pictures that conform to his own world view, as he is of course entitled to, and sometimes departs from expected liberal orthodoxy – as when he reportedly turned down Michael Moore for Sicko funding. The Canadian Skoll knows from personal experience the failures of nationalized health care. Superman takes aim at a few surprising targets, as well – like teachers’ unions and government bureaucracies.

The film opens with Guggenheim driving by three public schools in his neighborhood on his way to drop off his own kids—at a private school—and recalling his first education documentary of 1999, The First Year. Nothing has changed since then, he muses with regret, and thus was born the idea of Superman.

The film opens with Guggenheim driving by three public schools in his neighborhood on his way to drop off his own kids—at a private school—and recalling his first education documentary of 1999, The First Year. Nothing has changed since then, he muses with regret, and thus was born the idea of Superman.

Most of the children are poor in the film, and all of them are trapped in schools determined by where each family lives. One of the subjects of the present film, a fifth-grader named Anthony, is being raised in Washington, D.C. by his grandmother. His father is dead from a drug overdose; he never knew his mother. He wants to get a better education yet he doesn’t want to leave all his friends. He answers “bittersweet” when asked how he would feel if he really did win the lottery to get into SEED, a DC boarding school for inner city kids. This is what’s left for him, a child already burdened by loss, in DC, the film says, yet not one word about the voucher program in DC or President Obama’s phasing out of that city’s successful program.

But Superman does take on Democrat and Republic legislators alike and their alliance with what it considers the real enemy, the bulging PAC funds of the teachers’ unions. And the film praises bipartisan cooperation, too – specifically, that between the late Ted Kennedy and then President G. W. Bush that produced No Child Left Behind. Many people, though (including me) questioned that “unity” because it represented more government control – not less – of a problem that government itself caused.

This is where Superman goes irretrievably wrong. We endure the painful story of these beautiful children and their dedicated parents only to be urged on to … what? Send a text to Skoll’s website for mobile updates? Write an astroturfed letter to our governors, urging them to adopt a new blizzard of education standards? These have been formulated by Skoll’s assemblage of experts and appear to be a workaround for NCLB. I question how and why these experts arrived at their conclusions. The fact that they are unelected does not bode well, either, for future responsiveness to parents.

Superman has all the smart facts. Reading and math scores have not improved in 30 years; a number approaching 50% of our children do not graduate from high school at all. I would ask, then, why are solutions like distributing vouchers or dismantling the Department of Education (founded roughly 30 years ago) and returning schools to local and parental control considered too radical? Let it be said that I know many wonderful teachers and public employees, as well. I want to emphasize that the problem is mandatory union membership and union alliances with politicians and non-education groups. In Superman, we see placards at “teacher” protests against Chancellor Michelle Rhee from the ubiquitous ANSWER, for instance, indicating that something other than local education issues are at stake.

Slick websites and tweets and texts do not constitute a real answer to the problems presented by this otherwise moving film. Adding to the sticky quagmire of federal, state, and local rules and regulations for education, rightfully lamented by the film, will not cure the problem or force accountability. Freedom to choose just might. Why not reduce top-down solutions like national standards and national experts, and empower individual parents and local communities? Superman rightfully rues the lottery system, necessitated by the scarcity of truly effective charter schools now in operation. But how do we empower individuals? The voucher system, to me, represents a much quicker, more elegant solution.

Guggenheim is free to choose what he thinks best for his children because he has the money to pay for tuition. He feels terrible about it. But the Superman parents have money, too, available to them. It’s just that the government and their handmaidens – the education unions – mediate the transaction between family and school.

The only true accountability for schools will be realized when parents can vote with their kids’ feet, and take their voucher and their child to another school. The answer to bureaucratic failure is never more bureaucracy. The answer is freedom – because the answer is always freedom. I hope that the families who send their children to school every day know, like Guggenheim, that it’s ultimately their own free choice where they send them.

Posted on October 5th, 2010 at 10:36am.

By Jason Apuzzo. The Social Network took top honors at the box office over the weekend. I saw the film on Friday, and although I found it interesting the film was also curiously unmoving and somewhat clinical. Essentially it felt like a gossipy Vanity Fair article rather than a movie. Silicon Valley is apparently reacting to the film badly, believing that Hollywood doesn’t really understand them at all. They’re right. Basically, screenwriter Aaron Sorkin and director David Fincher don’t really know what to do with Mark Zuckerberg in this film other than to slap the usual geeky-Jewish-nerd template over him, and assume that his prime motivations for creating Facebook were: girls and money.

A motivation they seem completely incapable of understanding is: innovation.

And this, ultimately, is why the movie fails as a depiction of Silicon Valley culture. In an industry based on sequels, remakes and franchise properties, I’m sure it must be difficult for Hollywood people to grasp what makes the Silicon Valley guys and girls tick: a desire to innovate, to create technologies no one has ever dreamed-of before, to push the boundaries of science and industry. This is not what Hollywood has any interest in any more, to say the least. But a spirit of innovation is what makes people like Steve Jobs tick. Or filmmakers like George Lucas, or the Pixar guys, or Francis Coppola – all of whom decamped for the Bay Area decades ago, for reasons few people in Hollywood (whether liberal or conservative) seem capable of understanding.

Oh and incidentally, as of this month Steve Jobs’ Apple may currently be replacing Exxon as the most valuable company in the world, in terms of market capitalization. That’s another development the Hollywood guys probably don’t understand at all.

A fun little footnote here. Some years back when I was a graduate student at Stanford (I was studying lit), I had a buddy in the computer science department there. We would occasionally hang out at the computer lab late at night and shoot the breeze. Often there would also be these two other guys there, huddled off in a corner working on something. They always seemed busy, and intense – my buddy and I always wondered what they were working on.

I never gave those guys much thought until years later when I saw their pictures, and realized that those two dudes in the lab were … Sergey Brin and Larry Page.

And what warm, wonderful guys they were! 😉

• First it was MGM bankruptcy, then losing Guillermo del Toro, then labor troubles, and now a fire has burned down a crucial workshop in New Zealand that was to be used for production on Peter Jackson’s already-troubled Hobbit adaptation. Plus: word is now leaking that the 2 Hobbit films may be shot in 3D, at a cost potentially as high as $500 million. Is there really that much juice in this series? I sure hope so, for Jackson’s sake (and MGM’s).

• I was very sorry to read that one of my favorite directors, John McTiernan (Predator, Die Hard, The Hunt for Red October, Die Hard: With a Vengeance), just got sentenced to one year in prison for his role in the Anthony Pellicano wiretapping scandal. It could’ve been worse, though: he could’ve been forced to direct a Green Hornet sequel.

• Hugh Hefner’s life may be getting a BBC miniseries treatment, and Brett Ratner may be reviving the Beverly Hills Cop franchise, sans Eddie Murphy. Why do those two stories seem related? It must have something to do with bringing things back from near-death.

• Mary Jane is apparently going to be played by Emma Stone in the Spider-Man reboot. No surprises there. And you’ve probably already heard by now that Wonder Woman will be coming back to television, in a new series to be written and produced by David E. Kelley. Few details are available about what’s planned for this reboot, so we’ll be keeping an eye out …

• On the Sci-Fi/Alien Invasion front, Olivia Wilde of Tron and Cowboys and Aliens (and ACLU ads) has now been cast in (the project formerly known as)I.m. mortal. Plus, check out this interesting set visit to the forthcoming The Thing prequel/remake/reboot (see the picture above); Matt Reeves talks about Super 8 and also the potential of a Cloverfield 2; and Mad Men’s January Jones may be doing a lingerie scene for X-Men: First Class, so that’s a plus.

• AND IN TODAY’S MOST IMPORTANT NEWS … did you know that somebody did a prequel to Death Race, called Death Race 2: The Beginning … with Danny Trejo and Sean Bean? Neither did I, but apparently it’s going straight to DVD – and it also stars South African model Tanit Phoenix, who as a brunette might be a great candidate to play the new Wonder Woman on TV. Judge for yourself …

And that’s what’s happening today in the wonderful world of Hollywood.

Posted on October 4th, 2010 at 1:08pm.

By Joe Bendel. There was a time when Nicolae Ceaușescu got all the Iron Curtain’s favorable press. Many in the foreign policy establishment considered him reasonable, even reform-minded based on some shrewd public relations moves, like his measured criticism of the 1968 Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia. However, the 1989 Revolution ripped down the façade, revealing to the world the monster that had long oppressed Romania. Of course, every dictator sees himself as an enlightened Caesar – and has the state-produced propaganda to prove it. Culling 180 minutes from over 1,000 hours of archival footage, Romanian director Andrei Ujică assembled a video-collage of Ceaușescu’s life as it was perceived by the dictator and recorded by his state cameras in The Autobiography of Nicolae Ceaușescu (trailer above), which screens this Saturday during the 2010 New York Film Festival.

Defiant to the end, Nicolae Ceaușescu refuses to cooperate in the hastily assembled trial following the Revolution (he would say coup) that removed him from office. Indeed, his has been a life of destiny as we watch his storied career in flashbacks, courtesy of the state propaganda ministry.

From his meteoric rise following the death of his Stalinist mentor Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej, Ceaușescu might have displayed a bit of independence in foreign policy – but aside from his support for Prague Spring, this usually manifested itself in uncharacteristically warm relations with the Warsaw Pact’s Eastern rivals, the Chinese and Vietnamese (here was a man who could appreciate a personality cult). Still, he certainly seemed to enjoy entertaining western heads of state, including President Nixon (who also appears to relish his photo ops with one of the few world leaders he physically towered over). We watch as Ceaușescu celebrates birthdays, receives dignitaries, and opens party conferences. He briefly condemns a spot of hooliganism in Timişoara and then suddenly he is facing an ad-hoc inquest. Of course, the real story is much more dramatic and far bloodier.

From his meteoric rise following the death of his Stalinist mentor Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej, Ceaușescu might have displayed a bit of independence in foreign policy – but aside from his support for Prague Spring, this usually manifested itself in uncharacteristically warm relations with the Warsaw Pact’s Eastern rivals, the Chinese and Vietnamese (here was a man who could appreciate a personality cult). Still, he certainly seemed to enjoy entertaining western heads of state, including President Nixon (who also appears to relish his photo ops with one of the few world leaders he physically towered over). We watch as Ceaușescu celebrates birthdays, receives dignitaries, and opens party conferences. He briefly condemns a spot of hooliganism in Timişoara and then suddenly he is facing an ad-hoc inquest. Of course, the real story is much more dramatic and far bloodier.

More or less billed as an object lesson in film as a propaganda tool, Ujică did not set out to create a revisionist history or to humanize the permanently deposed dictator. However, the film might have that unintended effect on audiences not privy to Ujică’s underlying concept or his past work documenting the 1989 uprising in Videograms of a Revolution. This is a particular risk here in New York, where art-house patrons consider themselves politically sophisticated but are easily manipulated by propagandistic images exactly like those in Autobiography.

Running a full three hours, Autobiography is a hugely ambitious work, but frankly it is a grueling viewing experience. One scene of Ceaușescu fondling the bread of a well-stocked Potemkin market during a photo op makes the point. The second constitutes overkill. In fact, there is constant and deliberate repetition throughout Ujică’s film, as each Party conference and state visit blends into the next. Perhaps this is a deliberate strategy to convey the rigidly homogenous nature of Ceaușescu’s artificially constructed reality, but it is wearying for viewers looking for a lifeline to grasp unto.

As the highly problematic Autobiography currently stands, there is no footage that even mildly criticizes Ceaușescu’s twenty-five year misrule. How could there be? Any employees of the propaganda ministry not properly lionizing their master would have faced severe (probably fatal) reprisals. As a result, the entire film is much like Kim Il-sung’s massive welcoming ceremony, a hyper-real but static spectacle, ironic in its conspicuous lack of irony. Ujică proves himself a daring filmmaker, but to what end? Autobiography is ultimately a film for those who have an affinity the vintage aesthetics of the Soviet era, regardless of the messy history involved, essentially unreconstructed leftists and ironic hipsters. Not recommended, it nonetheless screens this Saturday (10/9) at the Walter Reade Theater as a special presentation of the 48th NYFF.

Posted on October 4th, 2010 at 9:13am.

By David Ross. In preparation for my film course (see here), I watched Godard’s A Woman is a Woman (1961) for the first time in years. [See the first 10 minutes of the film above.] I remembered the film as a wearisome deconstructive exercise brought to life only by Anna Karina in the lead role. The film was as tedious as ever, and La Karina as irresistibly kittenish. She poses, pouts, and purrs, in what may be the single greatest act of seduction – seduction of the camera, seduction of the audience – ever filmed. Of course, Karina manages to seduce none of the characters onscreen despite dogged effort. This is Godard’s little joke, or maybe part of his point.

What a cold and aloof ass Godard must have been to persist in his ironic games instead of allowing himself to be seduced, as Degas allowed himself to be seduced over and over again. Godard’s camera is busy making political and aesthetic points when it should be, as it were, making love. Karina and Godard married during the shooting of A Woman is a Woman. I suppose a man can be excused a certain sobriety with respect to the woman he sleeps with every night, but he cannot be excused an imperturbable irony. Godard’s clinical distance is an embarrassment to the male imagination and a travesty of what’s owed to a woman on her honeymoon. What a shame that at the height of her beauty and charm Karina wound up in a string of pretentious, sporadically brilliant Godard films and not in a string of delightful romantic comedies directed by someone like George Cukor or Billy Wilder. She might have been another Audrey Hepburn.

Oddly enough, A Woman is a Woman put me in mind of Mark Steyn. Karina’s character Angela desperately wants a baby, but she can find nobody willing to impregnate her. I couldn’t help construing or misconstruing this as an allegory of Europe’s plunging birthrates and demographic death spiral, of which Steyn is the poet laureate. Here’s a typical exchange between Angela and Émile Récamier as Brialy:

Angela: I want a baby

Brialy: You’re being unreasonable.

Angela: I want a baby

Brialy: Stop this madness

Angela: You’re being mean.

Brialy: I don’t like that tartan skirt on you.

Angela: Good. I’m not trying to please anybody. I want a baby.

Brialy: Stop this madness.

Angela: I’m going to the Zodiac [a strip club]

Brialy: Go and strip then. You disgust me.

Angela: Jerk. We can’t live off your lousy income. You’re such a coward.

Brialy: I’d rather be a coward than fool

Angela [sadly]: Why am I a fool for wanting a baby?

Brialy: Shut up or I’ll leave.

Angela: Where would you go?

Brialy: I don’t know. Mexico.

Angela: You’re crazy,

Brialy: No, you’re crazy.

Angela: I want a baby.

The camera then cuts to a Paris boulevard, where a man-in-the-street reporter type accosts a young man:

Reporter: Excuse me, could you sleep with this young lady so she can have a baby?

Pedestrian: It’s not a good time. I’m a bit busy today.

Procreation, as Steyn argues constantly, is an affirmation of continuity with both the past and the future (see here for a typical riff). It is a matter of believing in a narrative of history and choosing to participate. Modern Europe – where the non-immigrant birthrate is far below replacement level – seems to construe the future as somebody else’s problem, as something for state bureaucrats to work out while one holidays in Ibiza. Does Godard’s comedy pick up on something then latent – now patent – in the European zeitgeist? Perhaps not – perhaps so.

Posted on October 3rd, 2010 at 12:28pm.

By Jason Apuzzo. I saw The Social Network yesterday – and found it for the most part uninteresting. Despite some stand-out performances by Jesse Eisenberg, Justin Timberlake and Andrew Garfield the film failed to really grab me emotionally in any way. Part of the problem is that there doesn’t seem to have been anything particularly dramatic behind the rise of Facebook as a corporation. You could basically make the same movie about the rise of, say, Dunkin’ Donuts, to about the same effect.

[I hear Dunkin’ Donuts does over $5 billion in business per year, by the way. So don’t laugh.]

And so in lieu of spending hours writing a review about a film that didn’t grab me, on any level, I thought I’d post this video above that illustrates how David Fincher’s directorial style could quickly and efficiently be brought to bear in depicting the rise of other famous Silicon Valley ventures. Judge for yourself.

By the way, my understanding is that Mark Zuckerberg won’t be suing Sony, or any of the other people behind the making of The Social Network. They’re lucky, frankly. The people making the Google movie might not have the same good fortune.

Posted on October 2nd, 2010 at 10:53am.