By David Ross. Nazism was history’s most despicable moral perversion and criminal conspiracy, but too often the examination of Nazism goes no farther than moral condemnation. This posture is perfectly understandable, but it does nothing to further the understanding of Nazism as a philosophy and historical development. The difficult thing is temporarily to relax the impulse to condemn and to bring a degree of detachment to the analysis of Nazism as a system of thought. As one who frequently teaches literary modernism – Yeats, Eliot, Pound, Lawrence, Wyndham Lewis – I must constantly address a certain kind of romantic conservatism, and this naturally raises questions about fascism and Nazism. I tell my students something like this: “Its not enough to call Nazism evil, though certainly it is evil. You have to consider the nature and logic of its evil. You have to engage its ideas.” At this point, I usually insert that I am myself Jewish, which lowers eyebrows somewhat. Two deeply thoughtful documentaries, one German, one American, attempt just this kind of work and make for important lessons in the history ideas.

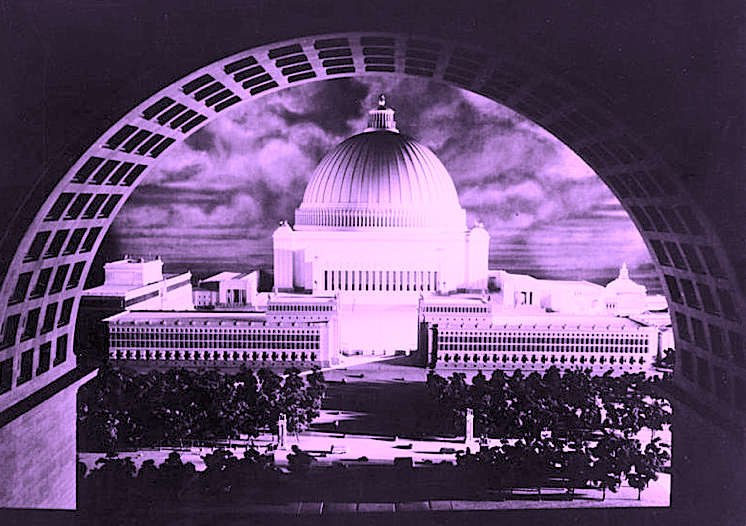

Peter Cohen’s The Architecture of Doom (1991) examines Nazi aesthetic theory and the Nazi obsession with art generally. Nazi artistic taste (a mélange of alpine-oriented romanticism and grandiose neo-classicism) was often kitschy and crass, but the Nazi cult of beauty was remarkably passionate and central. Hitler began as an artist, as everybody knows, but it’s less well known that he remained the most extraordinarily obsessed aesthete, buying and stealing works of art by the thousands and involving himself at every level with what may have been his greatest dream: the architectural recreation of Germany on a scale of classical magnificence to rival ancient Rome. The film’s crucial recognition is that Nazism’s aesthetic program partially or even largely drove its political and military program. Nazism did not conceive its program of conquest as an end in itself, but as a means of implementing the cultural and aesthetic renaissance that was Hitler’s chief fantasy. Likewise, the film clarifies the connection between Nazism’s aesthetic program and its campaign of hygiene, eugenics, euthanasia and genocide. Adulating the classical ideal suggested by the sculpture of antiquity, the Nazis conceived their murderous activities as a program of ‘beautification’ in the literal sense. The goal, according to Cohen’s film, was less to create a pure race than a physically beautiful race. The Nazis considered racial purity an indispensible basis of this beauty, but they did not necessarily consider this purity an end in itself.

This aestheticism does not in the least mitigate the Nazis’ vast crimes, but it does force us to move beyond the reassuring notion that Hitler was merely a maniacal sadist, a kind of Jeffrey Dahmer with a propaganda machine and vast army at his disposal. The scarier proposition is that aesthetic ideals we ourselves may share, or at least not entirely deplore, were mixed up in the vile stew of Nazism, and that ‘beauty’ itself may become a dangerous absolutism. Is our own culture implicated in this dynamic? Obviously we are not about to launch a racial genocide, but our popular culture may want to rethink its own extraordinary emphasis on physical perfection. Though this emphasis is not likely to lead to a renewal of the gas chambers, it may someday lead to a program of genetic selection and manipulation of the kind envisioned by a film like Gattaca. Mass-murdering the living is far worse than manipulating the unborn, but both programs share the dangerous premise that human beings are fundamentally stone to be carved, clay to be shaped. In this respect, The Architecture of Doom should give us pause.

Stephen Hicks’ Nietzsche and the Nazis (2006) delivers a whopping 166 minutes of philosophical disquisition in the attempt to explain the nature and impetus of Nazism. Unlike the graceful cinematic art of The Architecture of Doom, Nietzsche and the Nazis has the feel of a college lecture filmed on the cheap. It cuts between still photographs and Hicks himself speaking against a variety of nondescript backdrops, while the text itself is at best workmanlike. And yet Hicks, a philosopher at Rockford College in Illinois and author of a book likewise titled Nietzsche and the Nazis (2006), makes a lucid and thoroughly intelligent case that Nazism was not a function of economic conditions or social psychology or personal pathology – the usual notions – but of certain strands in the history of philosophy, and that it enacted ideas that were deeply embedded in the German culture and the German philosophic tradition. Hicks mentions Hegel, Fichte, and Marx, but gives primacy to Nietzsche, whom Hitler revered. Continue reading Lessons in Darkness